For the United States, the two big environmental flashpoints of 2016 were clearly the Flint, Michigan, water crisis and the Standing Rock Sioux’s rejection of the North Dakota Access Pipeline. Both of these major controversies were about the safety of American water resources. They also shed light on the importance of collecting and presenting evidence to help protect the environment.

The Standing Rock Sioux have waged a months-long campaign of principled civil disobedience to draw attention to the incredible potential consequences of a major crude oil pipeline crossing Lake Oahe, just one-half mile upstream from their reservation. Without their activism, pipeline developers would have relied on an evidence-poor environmental assessment that took none of the tribe’s concerns into account. Former US president Barack Obama halted construction of the pipeline; now current president Donald Trump seems determined to complete it, over the objections of both environmentalists and tribal advocates.

With the Flint water crisis, meanwhile, it took months of sustained public outcry, along with water testing by medical officials, academics, and even regular citizens, to force public officials to take this massive public health problem seriously.

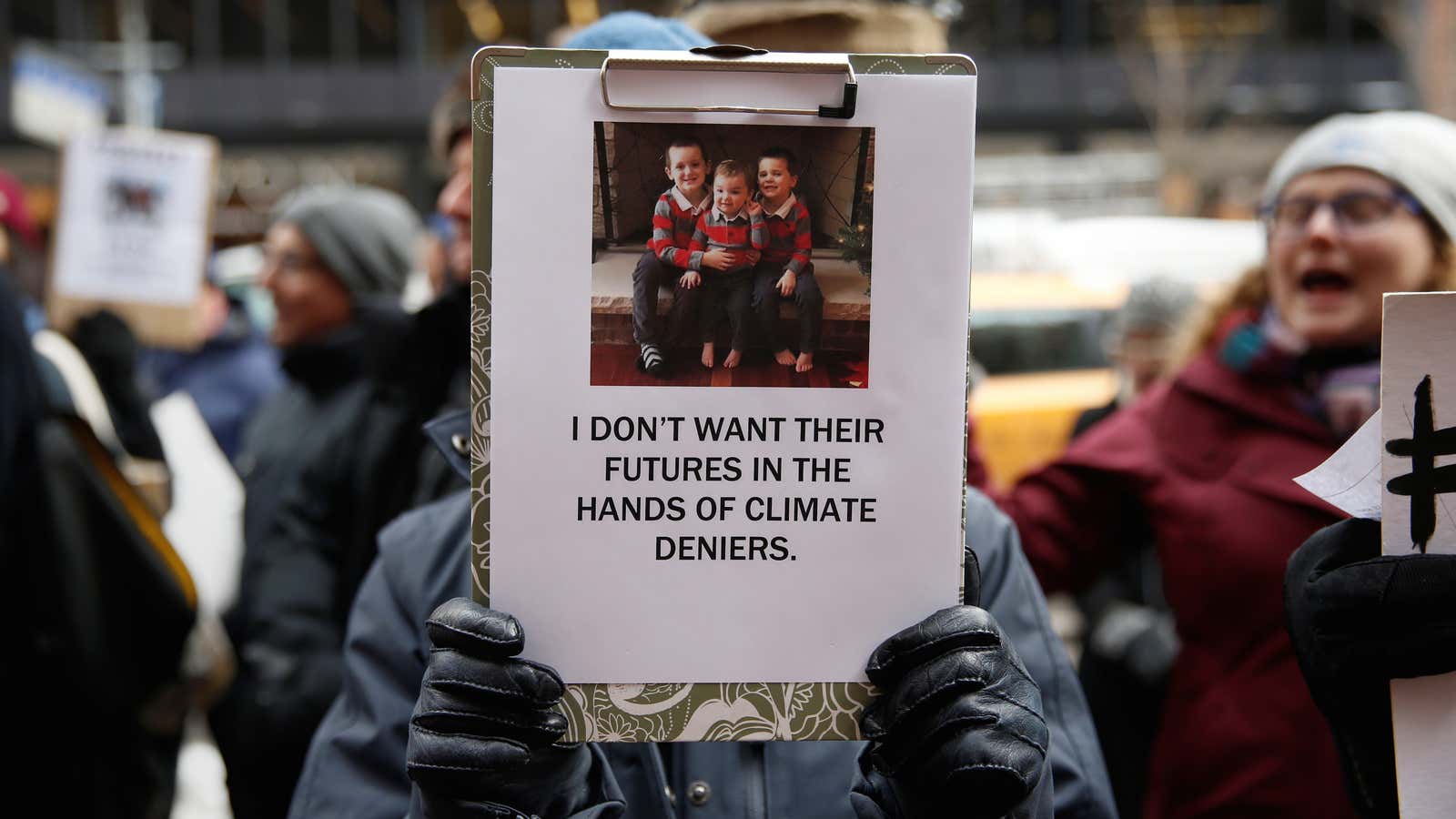

These stories show that even the strongest federal environmental regulations must be secured through rigorous evidence in order to function properly. If the Trump administration has its way, communities like Flint or Standing Rock will be shut out from the environmental oversight that gives communities a fighting chance at monitoring and ensuring their safety.

Already, some of our fears are being realized. On Monday, federal staff leaked news that the EPA had frozen its grant funding program, while USDA scientists have had their research funds frozen and were initially told to stop speaking to the media (although that order has since been rescinded.) Meanwhile, the EPA has reportedly been instructed to remove the climate change page from its website.

The Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI) has formed as an organized response to the Trump administration’s plan to undermine federal environmental science resources. Because access to and control over data is a key piece of effective regulation, we have taken action to systematically archive valuable environmental datasets, create usable nongovernmental data access, and preserve records of wide-ranging, ephemeral, web-based policy and program information. This monitoring and tracking work has also created an opportunity for providing rapid analysis of environmental regulation during the transition.

Trump has also hand-picked a wide range of extremists when it comes to environmental policy, from climate-change-denier Scott Pruitt, his nominee to head the EPA, to ex-Koch Industries lobbyist Thomas Pyle, who is the transition leader for the Energy Department transition. These are not just pro-business conservatives trying to keep environmental costs down. These are hardcore anti-environment appointees, many of whom have strong records of anti-science denial and obstructionism. This, coupled with indications that the administration will be working rapidly to roll back federal environmental policy, points toward a wholesale attack on environmental governance, with federal environmental science a key target.

This is where EDGI comes in. Formed as a decentralized team of about fifty social scientists and researchers immediately after the election, EDGI has focused on these two primary goals: documenting and analyzing the transition, and publicly archiving federally maintained data.

We started with a prominent guerrilla archiving event at the University of Toronto, organized by Michelle Murphy, Patrick Kielty, and Matt Price, which has spurred a series of similar events around the US. With extensive involvement from librarians and computer programmers, the initiative brings together expertise on environmental politics—especially environmental justice—with archival, data management, and software development skills.

Our approach relies on existing tools as much as possible while creating open-source programs and protocols as needed. With more than 100 participants, the Toronto event nominated over 3,000 pages on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) website to the End of Term Archive, developed a browser extension to streamline the data harvesting process, and worked on other software and protocols to better orchestrate future efforts. With an outpouring of support from tech communities we have been able to greatly expand our objectives beyond the EPA.

Much work remains to be done, but we have captured a significant proportion of federally maintained environmental data. We are also running weekly page captures of tens of thousands of federal web URLs so we can systematically analyze the Trump transition’s environmental aspirations and damage. Essentially, we are creating both an infrastructure for publicly maintained data resilience and a big data archive for tracking the restriction of environmental evidence.

The EDGI is not alone in its efforts, however. The Data Refuge project, hosted by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities, has been working with EDGI members to develop further tools for handling data that does not fit into the End of Term Archive and for linking efforts between events to avoid gaps and duplication. More events are planned for Ann Arbor and New York City targeting data hosted by bodies like the Department of Interior, the Department of Energy, and NASA. Through a commitment to open-source and free software principles, these events can maintain a decentralized structure in which different groups focus on the policy areas and infrastructure priorities that best fit their interests and skills.

When we think about the Dakota Access Pipeline or Flint’s degraded water infrastructure, we see David-and-Goliath stories of regular Americans struggling to defend their homes against forces far larger than themselves. But just as importantly, these are people without any special training or expertise trying to make sense of their worlds, from learning to negotiate regulatory language and expert assessments to learning how to do citizen water testing.

The Environmental Data Governance Initiative is an urgent response to a very clear threat to our already weak, existing data resources. The fact is that we understand very little about our environments. Without reliable evidence—without data—as historian and EDGI co-founder Michelle Murphy has shown, toxic environments are literally imperceptible.

When faced down by a $3.8 billion infrastructure project, partly financed by America’s president, the South Dakota Sioux repeatedly have insisted that they are not political activists or protestors but Water Protectors. From their point of view, it is unfair to get labeled a political activist simply for protecting one’s drinking water. Like the Black Lives Matter rallying cry, “I Can’t Breathe,” these are matters of survival.

Oddly enough, we find ourselves protecting data resources just as the Standing Rock Sioux protect their river. Reliable, relevant, and accessible environmental evidence is a necessary part of a safe environment.

Left to contend with an “alt-fact” political administration comfortable with obvious falsification, researchers know that even our existing environmental data resources are not good enough. As we look beyond the urgent threats of the presidential transition, we keep coming back to one difficult question: What will ensure that the right environmental evidence will be in the hands of those communities that need it?