Uber did nothing wrong, but that couldn’t stop the liberal outrage of #deleteUber

You’d almost think Uber had cosigned Donald Trump’s “Muslim ban.”

You’d almost think Uber had cosigned Donald Trump’s “Muslim ban.”

The outrage is palpable, the headlines ubiquitous. Esquire: “Here’s Why All Your Friends Are Deleting Their Uber Accounts.” The Huffington Post: “People Are Deleting Uber for Undermining Strike Against Muslim Ban.” Vox: “Why People Are Deleting Uber From Their Phones After Trump’s Executive Order.” Those are just the current top three results from a Google search of “delete Uber,” a topic that also spent a large portion of this weekend trending on Twitter.

So what did Uber do exactly? Something about Trump, something about strike-breaking… either way, something about which you should be very, very upset.

Or, try this: Uber did nothing wrong. Except find itself in the firehose of righteous liberal anger.

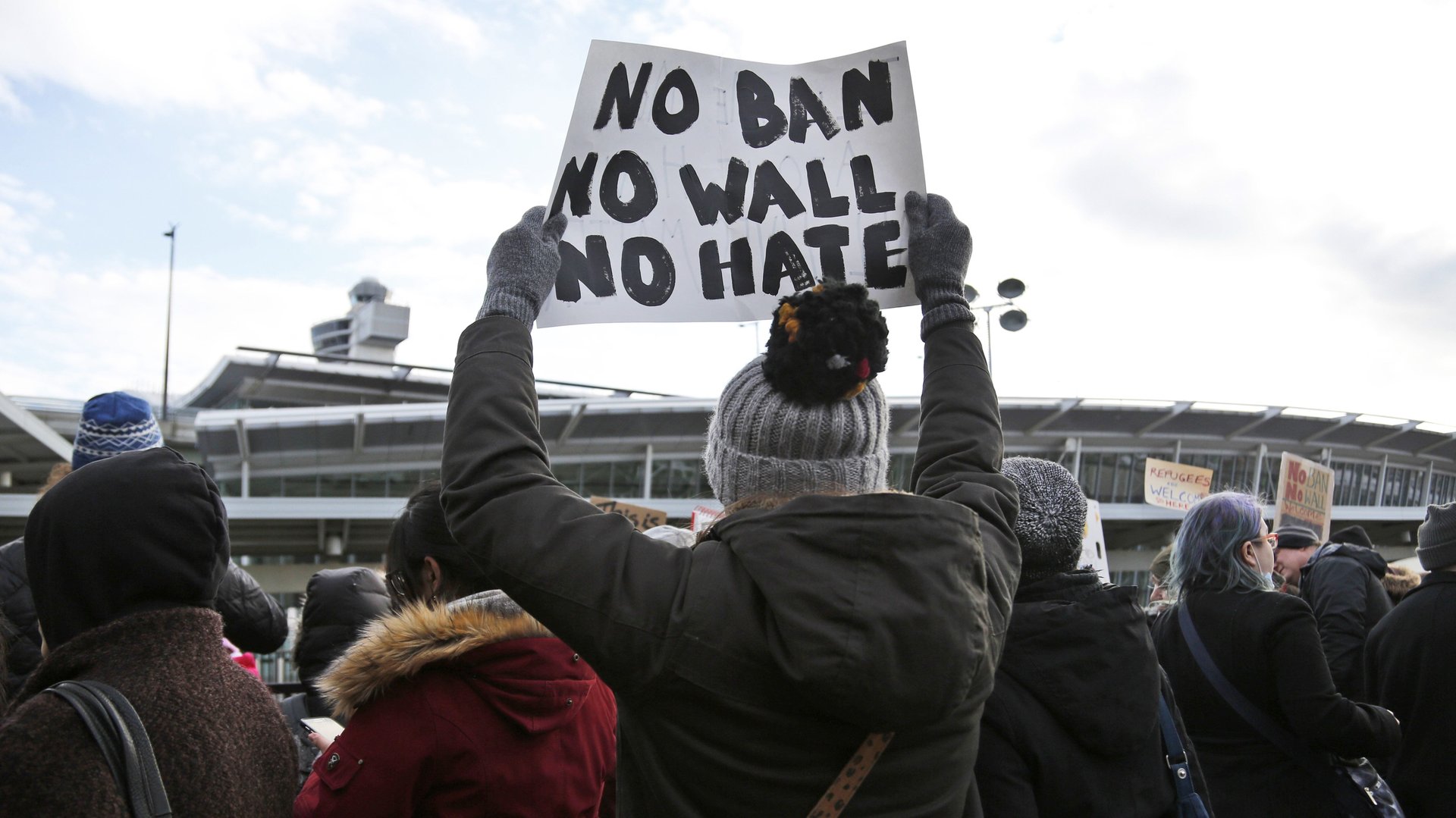

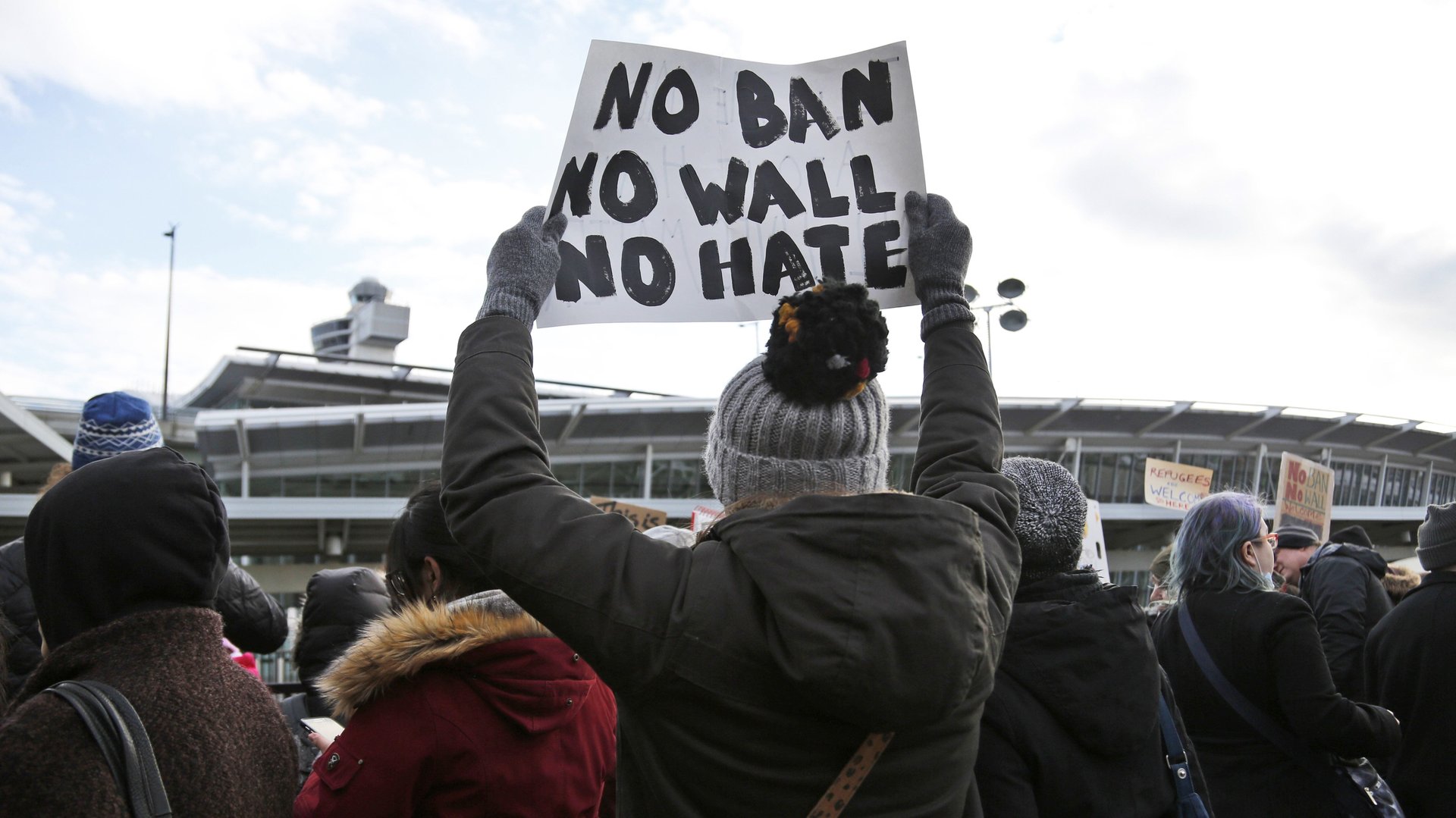

Here’s what what happened on Saturday (Jan. 28) at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, the site of one of several protests against Trump’s Jan. 27 executive order on immigration, and ground zero for the Uber backlash:

- Shortly before 5pm, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, an association of professional drivers in New York City with a large Muslim and immigrant membership, tweeted and posted on Facebook that its members would stop pickups at JFK from 6pm to 7pm, to protest Trump’s immigration order.

- At 7:22pm, as protestors amassed at the airport, JFK tweeted that the AirTrain, which provides service from nearby subway stops to the actual terminals, would only admit ticketed passengers and airport employees to “control crowding.”

- Also at 7:22pm, the Port Authority emphasized that the AirTrain limitations were being implemented for public safety.

- At 7:36pm, Uber’s New York City account tweeted that surge pricing—its system of increasing fares in areas with high demand—had been turned off at JFK.

- At 8:06pm, New York governor Andrew Cuomo ordered the Port Authority to reverse its AirTrain decision.

Then, at 8:38pm, it happened: A Twitter user spotted Uber’s tweet about surge pricing, and reissued it with scathing criticism.

From there the fallout was swift. Amid thousands of retweets, the same Twitter user pointed out that Uber CEO Travis Kalanick was serving on Trump’s business advisory team, saying Kalanick would “partner with anyone in the world” to increase his own profits. #DeleteUber was born.

Uber competitor Lyft seized on the moment, announcing a $1 million donation to the American Civil Liberties Union over the next four years. Kalanick, who earlier that day had said Uber was working to identify and compensate drivers affected by the immigration ban, came back with a stronger statement, calling it ”wrong and unjust.” He also said Uber’s lawyers would be on call to offer drivers legal support, and that the company was creating a $3 million fund to help thousands of drivers “with immigration and translation services.”

It was too late. The cycle of liberal outrage was fully underway, and that cycle is incredibly difficult—if not impossible—to stop.

Let’s return to Saturday night at JFK. The moment the taxi workers’ strike began and AirTrain service for non-ticketed passengers (i.e., protestors) was suspended, Uber was, operationally speaking, in a bind. If the company allowed prices to increase due to congestion—as it usually would—riders would have been furious and accused Uber of gouging during a civil protest (worse, imagine a newly released detainee having to pay five times the normal fare to get home). If Uber suspended service at JFK entirely—in solidarity with the taxi strike—protestors and people trying to get to their flights would largely be stranded, while drivers who did want to work wouldn’t have the option. So Uber did what was logically best: It turned off surge, ensuring that those who needed a ride could get one without paying extra, but didn’t force or even encourage drivers to keep working.

To be sure, there are plenty of reasons to dislike Uber. The company has broken local laws, attacked politicians, and offended entire cities. It has signed thousands of people into auto-financing arrangements with questionable terms and systematically misled its US drivers about how much they can really make on the platform. Uber has played fast-and-loose with user privacy, championing it to prying regulators while all but forcing riders to let its app track them constantly. Kalanick, before he refined his image, was known for saying obnoxious things like “hashtag winning” and “Boob-er.”

But for the most part, the people who got behind #deleteUber this weekend weren’t citing any of those reasons. Many seemed to not even understand what had happened. Instead, they read unsubstantiated claims that Uber had tried to bust a protest at JFK, or that its CEO had just joined a Trump advisory group (Kalanick joined the council on Dec. 14, and no one was deleting Uber then). They decided that Uber stood for everything wrong with corporate America. Many then installed Lyft, which has surged to fourth place among free downloads in the iOS app store. Had people mobilized behind a similarly unsubstantiated conservative cause, we might say they were duped by ”fake news.”

Could Uber have done more? Sure. Did it do a lot? Absolutely. Uber and the rest of Silicon Valley are in a league of their own when it comes to standing up to Trump on immigration. The tech industry’s rebuke to the president, which began with a careful statement from Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg on Jan. 27, cascaded as the weekend wore on. Google co-founder Sergey Brin and Y Combinator president Sam Altman joined protesters at San Francisco International Airport. Venture capitalists matched donations to the ACLU in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Meanwhile, corporate dissenters outside the Valley can be counted on one hand: Goldman Sachs, GE, Mastercard, Ford, Starbucks. But consumers aren’t pledging to stop eating at McDonald’s, shopping at Walmart, or buying cars from General Motors. And why would they? Those businesses don’t claim to care about the public good in the same way. While Google’s slogan was “don’t be evil,” McDonald’s was ”I’m lovin’ it.” Tech companies spent years catering to liberal values; when those values came on the line this weekend, the standards of corporate social responsibility were high only for them.

This story has been updated to include the date Travis Kalanick joined Trump’s business advisory council.