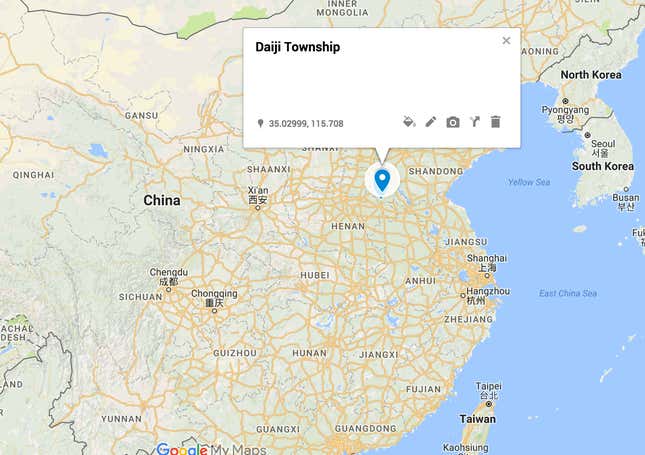

Heze, China

Daiji township, a dusty collection of villages in China’s central heartland plains, is an unlikely candidate to be one of the country’s leading e-commerce hubs.

The first word that local residents use to describe the area is “remote.” Until a few years ago, it took an hour to drive to the county seat, located 15 km (9.3 miles) away, due to poor-quality roads. Not that it mattered: Nobody had enough money to buy a car, and the township, like many rural areas in China, had been mostly drained of its working-age residents, who had all left the countryside behind for higher wages as migrant workers along the coast. Heze, the jurisdiction in which the township sits, was described in a recent magazine article (link in Chinese) as a place “synonymous with backwardness, the unwanted stepchild of Shandong province.”

When Su Yongzhong was reassigned from a neighboring township to become the Communist Party secretary overseeing Daiji in 2013, even he was surprised by the poverty. The province (link in Chinese) designated two villages within the township as “wearing the hat” of poverty. The nearby towns in which Su had previously been stationed had at least a small factory or two; Daiji had no industrial base whatsoever.

Today, the township and its surrounding area are China’s domestic capital for one rather specific category of products: acting and dance costumes. Half of the township’s 45,000 residents produce or sell costumes—ranging from movie-villain attire to cute versions of snakes, alligators, and monkeys—that are sold on Alibaba-owned Taobao, the nation’s largest e-commerce platform.

Daiji sold 1.8 billion yuan ($26.2 million) worth of costumes in 2016, and local officials guess the entire county sold nearly three times that, or about 70% of the costume market on Taobao. In Dinglou village, where the industry first started to grow, 280 of the 306 households run Taobao businesses. Most of the rest cannot work; if they could, residents say, they would be selling on Taobao.

Much has been written about China’s rural e-commerce boom, with these so-called “Taobao villages” now a national policy priority in rebuilding rural China and eliminating poverty. Vice premier Zhang Gaoli, a former Shandong party secretary and now one of the most powerful officials in China, visited Daiji in late 2015 and praised (link in Chinese) the township’s contribution to decreasing poverty.

In November 2016, the State Council Office on Poverty Alleviation, along with 16 other ministries, released guidelines calling for a massive expansion of e-commerce in rural areas as part of the fight against poverty. By 2020, the guidelines state (link in Chinese), impoverished rural counties should quadruple their e-commerce sales.

On the side of a building across the street from the first grouping of individual factories that cropped up in Daiji, a slogan is painted in large red letters (see the image at top). It reads: “Through Taobao, you can escape bitter days. E-commerce runs toward the road of happiness.”

China’s president Xi Jinping has vowed to eliminate absolute poverty in China by 2020, staking some of his reputation on leaving nobody behind in creating a “moderately prosperous society.” There are still more than 56 million people in China living in poverty (paywall), according to China’s national income standard of 2,300 yuan per year in 2010 constant prices (now approximately 3,000 yuan, or $436). The government projects (link in Chinese) the cutoff will rise to about 4,000 yuan ($582 at current exchange rates) when the poverty elimination deadline arrives in 2020.

Boom town

Ding Peiling’s small, hangar-like factory floor sits on the edge of his plot of land in Dinglou village, facing the recently paved road that heads into town. In one room, two middle-aged women from surrounding villages are ironing World War II-era army nurse costumes for yet another film about that war, which is remembered in China as a heroic struggle against Japanese militarism. The women had previously farmed nearby plots of land; now, they have found better wages out of the fields and much closer to home.

Ding, unlike nearly every other adult in the village, never left. A slim man of 60 with big glasses and dark, sun-worn skin, he graduated high school and became a teacher. He originally taught math and language arts, but the pay was low. It was only in the mid-1980s, after 13 years of teaching, that he found another opportunity. An artist in a nearby village painted background canvases for photo shoots, but was too busy painting to sell them. Ding and his cousin became door-to-door salesmen for photo backdrops. The market eventually shifted to photo costumes and then to general performance costumes, which offered a larger consumer base. Around 2013, only Ding and a handful of other households were engaged in any business besides subsistence farming.

Su, as the new township party secretary at the time, saw a development opportunity. The roads were too broken to support delivery trucks, so Su took matters into his own hands, residents say: He and his fellow township government officials went out and fixed the roads themselves. They laid fiber-optic cables—they have “internet faster than in Shanghai,” he claims—and he wrote an open letter encouraging college graduates and migrants who had moved to cities to come back to the countryside.

As part of the state’s targeted poverty alleviation campaign, the township government sponsored e-commerce and clothing-production training classes, provided low-cost loans, and encouraged successful entrepreneurs to prioritize hiring locals who remained below the poverty threshold. In less than four years, 6,300 people in Daiji and its surrounding county have moved above the official poverty line due to e-commerce sales, according to data (link in Chinese) provided by Alibaba’s research arm.

Alibaba says that, nationwide, 18 villages considered to be in poverty by the national government are now Taobao villages, selling more than 10 million yuan ($1.45 million) worth of goods online per year. It estimates an additional 200 villages designated as impoverished by provincial poverty standards—based on higher income thresholds—have reached a similar sales marker. Villages in Hebei province’s Ping county, a few hundred kilometers north of Daiji and a nationally designated poverty area, produce children’s bicycles (link in Chinese). Meanwhile, in one village in the southwestern province of Yunnan, members of the Bai ethnic minority sell silver handicrafts (link in Chinese), recording 19 million yuan in sales on Taobao in 2015.

In Daiji, Su’s efforts elevated him to an almost mythical status among villagers, who had previously had a contentious relationship with local officials. Yet Su insists that what is happening in Daiji can be replicated and expanded elsewhere. “Every place has its own unique products,” he says. “All they have to be able to do is sell them online.”

“Moderately prosperous”

The fact that China’s development is responsible for the vast majority of global poverty reduction in the past 30 years is well-known around the world. It is not lost on the Chinese government either. Chen Xiwen, former deputy head of the party’s Central Rural Work Leading Group, said in a speech (link in Chinese) to the National People’s Congress in January 2016:

If we still have many people under the poverty line in 2020, it will affect the quality of a moderately prosperous society. Our people and international society will doubt us. If we can get people out of poverty under current standards by 2020, 10 years ahead of the proposed United Nations sustainable development agenda, it will effectively demonstrate to the world the party’s leadership and the advantages of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

With only a few years to go before the 2020 deadline, the central government boosted its budget for poverty alleviation funds by 43% in 2016 to more than 66 billion yuan. Provinces added another 40 billion yuan in funding. The added emphasis on poverty elimination follows a nationwide poverty identification campaign in 2013 that deployed thousands of cadres to identify all impoverished households based on income levels, and to subsequently target funds directly to those households through projects approved by higher levels of government.

In its five-year plan for poverty alleviation released in December, the State Council, or the cabinet, called for fiscal, financial, land, and personnel policies to contribute to targeting the 128,000 poverty villages listed in the national poverty identification directory. A central government plan (link in Chinese) released two months earlier lays out how to share central and local responsibility for poverty alleviation, while also reiterating rules tying the evaluation of local government officials’ performance to poverty alleviation progress.

Alibaba, the internet giant behind Taobao, has offered its support as well. It now has four programs (pdf) devoted to promoting its platforms in the countryside. It’s focused especially on the central and western regions, where the company will invest 10 billion yuan to build 100,000 Taobao service centers in remote areas and expand logistics and training to bring villages up to speed for how to Taobao-ize their economy. The central government has signed agreements with both Alibaba and Jingdong, another major platform, to spur e-commerce development in the name of poverty alleviation.

“E-commerce can still grow even bigger,” says Yu Jiantuo, a poverty alleviation expert at the China Development Research Foundation. “Ant Financial [Alibaba’s finance arm] started microfinance to small businesses in 2010, and its microfinance arm has already done four times the credit volume that Grameen Bank has done in 39 years,” adds Yu, referring to the microcredit organization founded by Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus.

Reversing the brain drain

Yet despite local optimism and high-level government support, many of the areas mired in the country’s most intractable poverty may have difficulty capitalizing on the e-commerce boom. Daiji does have an advantage over other impoverished areas, observers say: Its flat plains eased the creation of roads and infrastructure.

Much of the remaining poverty in China exists in places where economic growth cannot easily reach, such as mountainous areas, as well as the remote central and western regions. Of the more than 1,000 Taobao villages in China, only 25 are located in these areas, according to Alibaba. Some areas have found ways to create distribution and logistics networks despite the difficult climate, but most still face large obstacles that even high-level support has not yet managed to overcome.

It also takes concerted effort and extraordinary dedication from government officials to transform villages starting from nothing into national production centers. “For a rural area to succeed in building e-commerce, all stakeholders need to cooperate,” says Cui Lili, an associate professor at Shanghai University of finance and economics. “But in poorer areas, the government responsibility and role is even greater because it is possible that the entire business ecosystem relies on their guidance.”

Most importantly, the country’s poorest areas, devoid of working-age population, face a shortage of laborers with skills adapted for the new economy. “When everyone left, it was a big loss for those areas,” says Yu Jiantuo. “It’s not an issue of the number of people leaving but of the type of people who were leaving.”

The last time China experienced a rural industrial boom, collectively owned township and village enterprises (TVEs) leveraged plentiful labor, local government support, and a very low bar for consumer demand to rake in huge profits and create millions of rural jobs during the 1980s and early 1990s. TVEs were necessary, argued legendary rural sociologist Fei Xiaotong, in part because it would help reverse the “brain drain” from rural to urban areas.

Su’s open-letter campaign to recruit migrants and college graduates back to Daiji began during the Lunar New Year holiday in early 2015. It added to efforts already underway: Since the Taobao boom began, local officials say that more than 5,000 migrant workers previously staying in cities, including hundreds of college graduates, have returned to run businesses in Daiji.

But the town still needs more skilled workers. “All of the college students who have come back have succeeded,” explains Ding Peiyu, the younger cousin of Ding Peiling. “Now we need to go out and find more.”

Ding Peiyu offers room and board to college graduates from nearby counties or cities, and has set up some computers for them to use, but luring outsiders to a rural village is a tough sell. In the busiest months of the year, overwhelmed by orders, the town’s largest businesses have resorted to outsourcing production to factories in other provinces. It is a difficult yet enviable problem to be facing, and one that was unthinkable a few years ago.

As sales increase, residents are now setting their sights overseas. The township government will soon break ground on its third industrial park to house more factory floors and sales offices. Taobao entrepreneurs in Daiji have started selling costumes abroad, particularly to Malaysia, Vietnam, and other countries in Southeast Asia. The next step, they say, is to improve the quality of the costumes enough to reach higher-cost markets in Europe and the United States.

Ding Peiling, who has seen all of the changes firsthand, has an even more ambitious goal. “I want all of China, and all of the world, to know about Dinglou village.”