In Seoul, a new sharing economy takes hold—one that leaves Uber and Airbnb in the cold

Seoul mayor Park Won-soon wants to make the South Korean capital a global role model for the sharing economy, but he’s defending the city fiercely against the very startups that have shaped the concept.

Seoul mayor Park Won-soon wants to make the South Korean capital a global role model for the sharing economy, but he’s defending the city fiercely against the very startups that have shaped the concept.

Ever since the second-term liberal mayor entered office in 2011, the 60-year-old Park—whose short-lived run in Korea’s presidential race ended last month—has been promoting his “Sharing City” project. The idea is to foster local startups that will ultimately break up economic dependence on Korean giants like Samsung and LG, whose sheer dominance over the economy and politics has even played a role in the crippling scandal surrounding president Park Geun-hye.

Yet the mayor’s vision of the sharing economy has been at stark odds with large global startups that tried unsuccessfully to shake things up in Korea. Despite Korea’s tech-savvy image thanks to the success of Samsung and its extraordinary internet penetration, anachronistic paradoxes like Korea’s relentless addiction to Internet Explorer and the continued domination by massive conglomerates show the country struggles to let go of old ways.

Uber’s entry into Seoul in particular became an ugly saga that saw founder Travis Kalanick get indicted. Airbnb recently faced pressure to delete all “illegal” accommodations—or 1,500 out of some 24,000 of its listings nationwide, according to the company—and is still embroiled in complaints with the Korean government. Park is one of the mayors from New York to Paris pushing for uniform regulations over Airbnb in their cities.

Park defends his city as a free-market economy that wouldn’t survive if it weren’t open to foreign companies. But actions against these Silicon Valley giants may speak louder than words. The mayor draws the line between “innovation” and “disruption,” insisting that these startups should be welcomed—as long as they follow the rules, he said during an interview at his office in Seoul.

Park said that as Uber was ”very stubborn” and stuck to its own operating methods, he “had no choice” but to uphold Korean laws, but nevertheless felt it necessary to work toward compromise with the ride-hailing giant. By the time Uber launched a version of its high-end Uber Black service that complied with the government’s requirements, KakaoTaxi, a taxi-hailing app created by the country’s mobile messaging giant Kakao, had already cemented its market dominance.

But Park denies the popular perception that Korea was being protectionist by bowing to the local taxi union’s demands to curb Uber’s foray, and emphasizes that the regulatory push against Airbnb was for safety’s sake. He said the government should rectify “unreasonable” regulations, but that Airbnb should also abide by “reasonable” ones, such as making hosts register their listings and ensuring basic sanitation, safety, and taxes.

But perhaps with Uber’s history in Korea in mind, Airbnb was much more compliant, having met several times with the government to negotiate, Park added. He even expressed admiration for Airbnb’s zero-to-hero startup story, and cofounder Joe Gebbia is part of Seoul’s sharing economy advisory council.

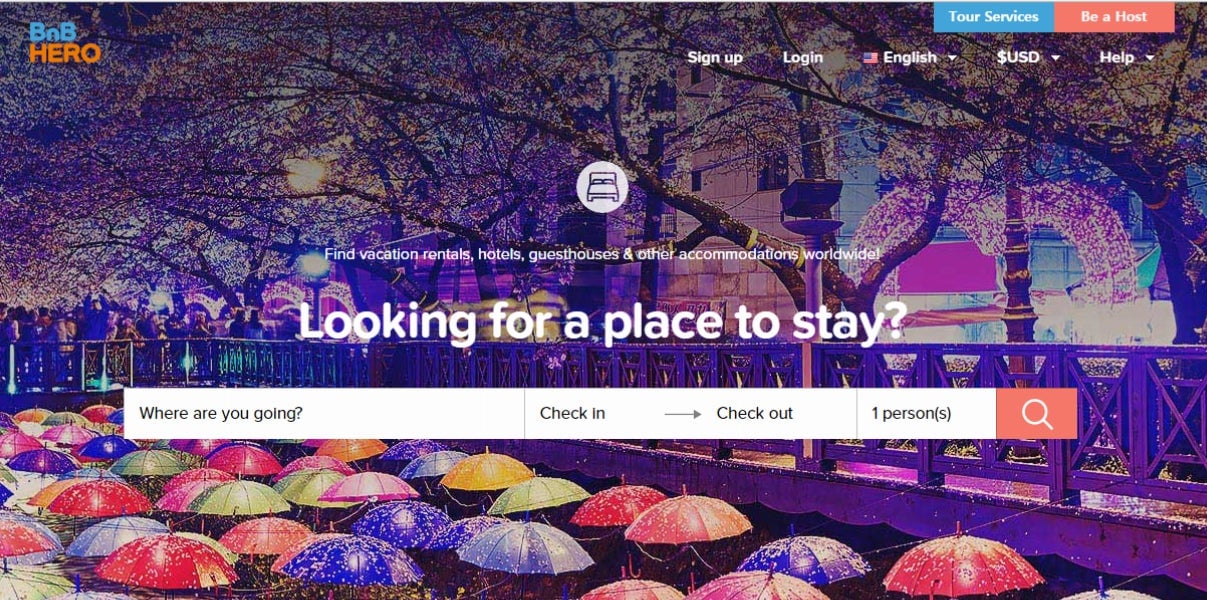

Rather than pander to global tech companies, Park said his sharing economy vision centers on “restoring a sense of community” from Korea’s traditional past and fostering local startups. His signature Sharing City project, launched in 2012, assists Korean startups like Airbnb clone BnBHero, which even mimics the Silicon Valley company’s previous website design, and SoCar, a car-sharing platform that has attracted 2.5 million users since 2011. Of 70 registered sharing economy startups, the top 12 have raised a collective 94 billion won ($83 million), according to city data.

Despite the investments, critics point out that a lack of successful role models, over-dependence on government funds, and outdated regulations keeping these startups from scaling. None of them have global reach. One Seoul-based entrepreneur, who requested anonymity, said his sharing economy startup was teetering toward closure because a permit problem was making operations prohibitively expensive, and the related city department did not address his concerns.

Yet he holds strong to the idea that Seoul needs to become a city that innovators can flock to. Park defends the Sharing City idea as being in its early stages while complaining that regulations by the central government that continue to benefit the giant conglomerates are beyond his control. But as major Korean exports like smartphones, cars, and semiconductors falter under increasing global competition, Park is betting that his grassroots-led strategy is necessary for Korea’s next-generation economic model.

“The regulations for [conglomerates driving the economy] were created in the past paradigm,” said Park. “But in the future it’s going to change.”

Correction: Airbnb deleted 1,500 of its listings in Korea. A previous version of this story said it was pressured to delete up to 70% of its listings.