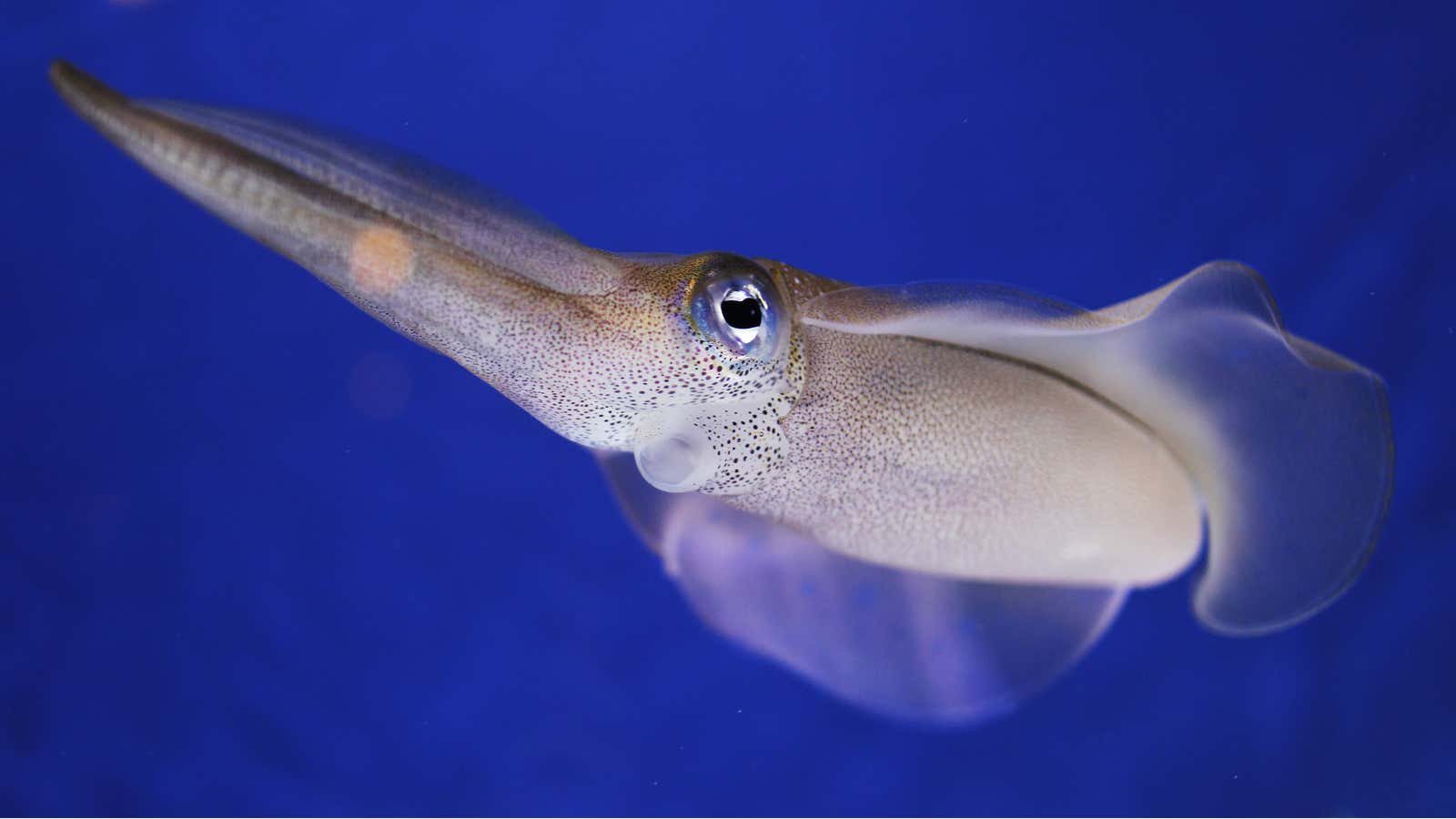

We know cephalopod brains are big. And disarmingly effective. But it turns out they’re are even more dazzlingly complex than we’d realized. The latest surprise comes from studying not their brains, though—but, rather, their skin. Or, more specifically, the dizzying medley of speckles, stripes, and colors that squid (and other cephalopods) can cycle through in mere seconds, a phenomenon Wired explores in detail.

Scientists long ago picked up on the fact that squid communication, like that of other cephalopods, is skin-based. And though they don’t understand the specifics, they know that certain patterns seem to signal the desire to, say, mate, or fight. (Sometimes these changes are simply to evade predators by blending in with their surroundings.)

These changes of decor can get incredibly complex, with one body part going polka-dotted at the same time as another is lined with stripes—and still another turned solid black. This lets squid send mixed messages (literally). For instance, while a squid might threaten a male competitor on its right side, its left side might be sweet-talking a potential mate.

This squid-skin psychedelia is courtesy of tiny muscle-bound pigment cells that act sort of like pixels. A part of the squid brain called the optic lobe directs the muscles to push and pull the pigment cells, creating the wild array of colors and patterns.

Based on our knowledge of our own brains, you’d expect a certain location within the optic lobe to control the color and pattern of a specific body part. However, Chuan-Chin Chiao, a neuroscientist at Taiwan’s National Tsing Hua University, experimented on the brain of an oval squid—and found that it didn’t operate that way at all, as Wired details. Instead of corresponding to body parts, different regions of the optic lobe, when stimulated, generated different combinations of the 14 skin patterns lighting up various squid body parts. If Chiao’s hypothesis is right, it would explain how squids can flash through one patchwork of colors and patterns to another, and another, and another—all within seconds.

There’s much more to map in the optic lobe before we can know that for sure. Having developed a good hunch as to how squids operate these combinations, Chiao told Wired that he is now focusing on the why—lining up pattern combinations with the context of these communications to decipher the squid-skin code. Or as it might seem to squid, eavesdropping.