The US National Security Council was created 70 years ago, in response to a rising threat from the Soviet Union, to advise then-president Harry Truman “on integration of domestic, foreign, and military policies relating to national security and to facilitate inter-agency cooperation.”

Since then, the NSC has served as a virtual traffic cop in some administrations, coordinating how information and ideas flow between the president and the thousands of experts in intelligence agencies, state, and defense departments. In others, it has been a policy advisor and advocate, with a real voice in presidential decision-making. In some administrations, the council was comprised of just a few dozen employees; in others, it’s had as many as a few hundred.

But it has never been in as much turmoil as it seems to be in now, security experts say.

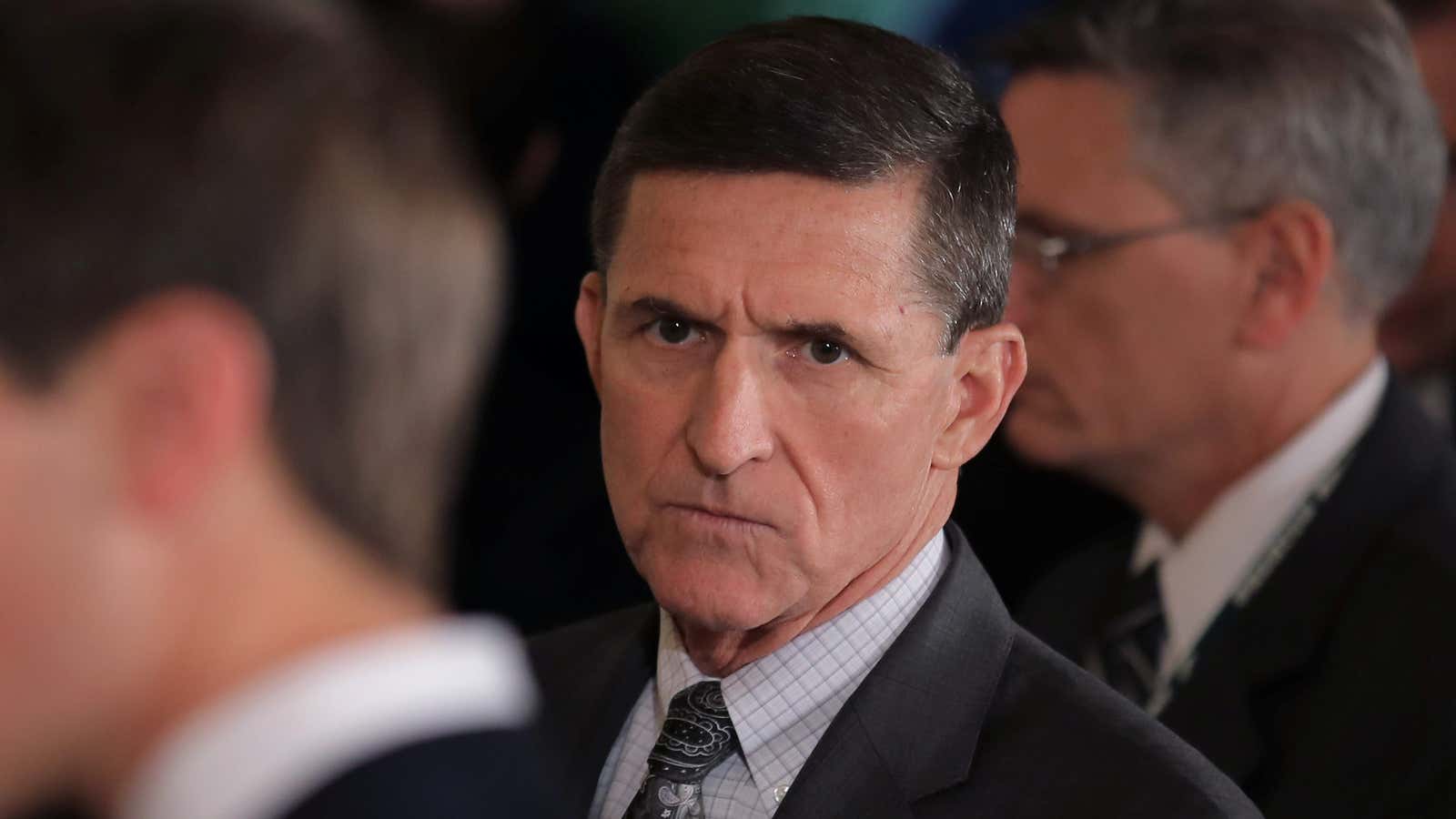

The departure of Gen. Michael Flynn as the head of the NSC late on Feb. 13, after less than a month in the job, caps off weeks of chaos and internal jockeying inside the council, and leaves US president Donald Trump, head of the world’s most powerful military and largest economy, without a framework to get information or make decisions on national security threats.

That probably suits Trump just fine—he and his small group of advisors entered the White House with a disdain for career civil servants and government experts, and a long-stoked hatred of anyone previously attached to the Barack Obama administration, as many current State and Defense experts are.

The situation, however, is alarming Republicans, Democrats, and the military alike.

John McCain, the Republican senator from Arizona, called the resignation “a troubling indication of the dysfunction of the current national security apparatus,” at a time when the US “confronts the most complex and diverse array of global challenges since the end of the World War II.”

“It’s not just General Flynn,” Senator Ben Cardin, a Democrat from Maryland, said Tuesday. “It’s the matter in which this whole relationship has been handled and the manner in which America’s national security has been further compromised.”

On Jan. 26, the Department of Justice informed the White House’s that Flynn had conversations that could have been inappropriate with the Russian ambassador to the US. But he wasn’t asked to leave until Feb. 13, White House press secretary Sean Spicer said on Tuesday (Feb. 14). A White House review found “there was nothing wrong or inappropriate about those discussions,” Spicer said, but the president lost trust in Flynn, after the general “continued to maintain” that those conversations had not occurred.

“We’re in an unprecedented situation,” said Stephen D. Biddle, a defense policy fellow on the Council on Foreign Relations, and former advisor to the US military in Baghdad and Kabul. Without coordination between experienced foreign policy makers, defense, and intelligence agencies, Biddle said, there’s any number of things that could go wrong. Among them:

- “It is entirely plausible we could do something that could seriously sour our relations with China,” and put us on a road that leads to war in a couple of years, Biddle said. Trump’s controversial strategic advisor Stephen Bannon said last March that he believes the US and China are headed for war over the South China Sea.

- In another worst-case scenario, “poorly conceived executive orders on immigration could have the effect of improving recruitment prospects for Al Qaeda, the Islamic State and other terrorist groups,” Biddle said. Those recruits could conduct more terrorist attacks in the US, sparking the administration to craft an even tougher stance on Muslims and liberties in the US—creating “a spiral of increasing terrorism.” Already, jihadist groups are calling Trump’s executive order on immigration the “blessed ban” because of its impact on recruitment.

- “We could end up overreacting” to something that Iran or North Korea does, Biddle said, a “from-the-hip” reaction that paints the US into a corner, and into a war it didn’t choose. Flynn himself put Iran “on notice” at the beginning of the month.

Biddle blames the failure of intelligence and decision-making at the NSC for the US’s ill-fated invasion of Iraq and ouster of Saddam Hussein, and the failed Afghanistan policy of Obama’s first term. Poorly made decisions can “lead you on a spiral to war” Biddle said, and that’s something good staffing at the NSC is supposed to prevent.