UK and US researchers using behavioral economics to improve police recruitment are starting to attract attention from police chiefs struggling to diversify their workforce.

Almost half a century ago, the US Commission on Civil Rights wrote (pdf) that racial disparity and tense race relations had made it harder for minorities to have equal employment opportunities as policemen and firemen “than in any other area of state and local government.” Decades of academic research and policy interventions to try solve this issue have produced underwhelming results, despite the importance of police diversity to developing trust and legitimacy (pdf) within communities. A 2015 analysis found that in the US, minority groups are underrepresented (pdf) among sworn police officers by an average of 24 percentage points when compared with the general population.

But research and pilot projects in the US and Britain that focus on tweaking small, typically overlooked details in the recruitment process are showing some promising results. These projects are conceived by the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), a company created by former prime minister David Cameron that uses the principles of behavioral science to improve public services.

In partnership with What Works Cities, a Bloomberg Philanthropies initiative to increase the use of data in public service delivery, BIT decided to test whether behavioral science could help with recruiting a more diverse staff pool.

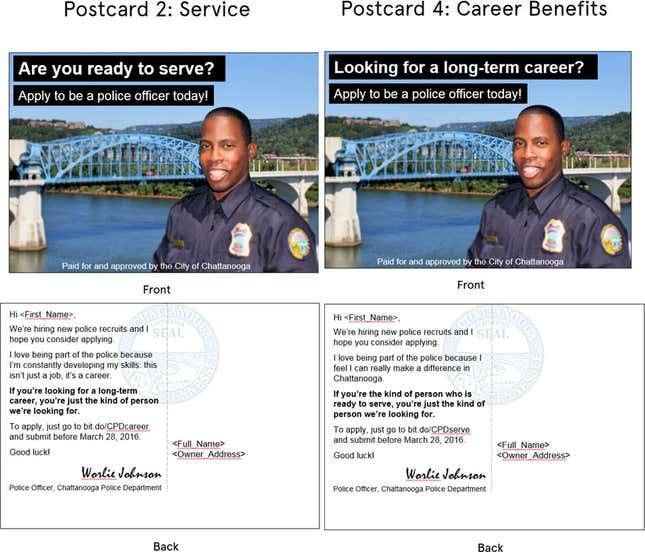

Elizabeth Linos, head of research and evaluation at BIT’s North American outpost in New York, says the team started by looking at the recruitment messages used by police departments, many of which focused on the job’s public service aspect. Using the philosophy that “how we hire determines who we hire,” her team tested different versions of a recruiting postcard in Chattanooga, Tennessee, last spring, to see which messages clicked.

African Americans and other minorities represent 21% of Chattanooga’s police force, compared with 40% of the local population. Mayor Andy Berke and police chief Fred Fletcher are keen to better align the two.

“We need a police force that looks like the citizens it serves,” Berke says.

Linos’ team produced four cards for the Chattanooga police, each highlighting an aspect of joining the force: the opportunity to serve, the impact on the community, the challenge of the job, and career benefits. Using the voter registration database, BIT sent out almost 10,000 cards to a randomized group that mirrored the ethnic breakdown of the general population and was within the age range eligible to apply for police service.

They tested the effects against a randomized control group of almost 12,000 with similar parameters. To mimic Chattanooga’s regular recruitment process, the control group received no postcard, but could discover the job through the normal recruitment efforts—a posting on the police website, police attendance at career or school fairs, and police radio advertisements. Traditional messaging was either descriptive in nature, such as the job posting on the police website, or tended to emphasize the opportunity to serve, says Linos. BIT matched the names of applicants to those in their control or target groups to track who applied.

Forty eight people responded to the postcards. While the postcard highlighting the opportunity to serve showed no significant difference from not sending a postcard at all, the challenge and career benefits postcards tripled the number of candidates. This effect was even more pronounced for people of color. They were 50% more responsive than their white peers to messages emphasizing career benefits and the challenges of the job.

Given that black and Hispanic people in the US are more likely (pdf) to earn considerably less than their white or Asian peers, the stability and regular promotion schedule of law enforcement careers may have been a particular pull. The exercise “taught us that direct engagement produces results more quantifiable than a wide audience marketing,” “says Chattanooga’s police chief, Fred Fletcher.

The approach of BIT, established in 2010 and co-owned by the UK government, is rooted in “nudge theory,” a not-uncontroversial mix of behavioral economics and psychology which makes small tweaks to existing policies and practices to try push people to make better choices—earning BIT the nickname, the “Nudge Unit.” The theory, which examines how biases, social interactions, and the way choices are represented can factor into decision-making, has gained prominence since the recession. Behavioural economists point to the downturn, and the failure of traditional economists to predict such a massive collapse, as evidence that the traditional economic understanding of individuals as rational, utility-maximizing agents is incomplete. A bipartisan commission (pdf) looking into the causes of the financial crisis agreed. “The crisis was the result of human action and inaction, not of Mother Nature or computer models gone haywire,” reads their 2011 summary report (pdf). “To paraphrase Shakespeare, the fault lies not in the stars, but in us.”

Since publishing a book on nudge theory in 2008, proponents Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler have been advising policymakers across the world (paywall) on how to use it to make government more effective.

In another example of how this theory could be applied to diversity efforts, BIT tested whether two processes were causing minority candidates in constabularies in Avon and Somerset to drop out of the recruitment process: “belonging uncertainty,” where members of socially stigmatized groups are more sensitive to issues of social belonging, and “stereotype threat,” the fear of reinforcing a negative stereotype of one’s group.

BIT found that, when taking a situational judgement test, certain cues were contributing to the attrition rate of minority candidates. “Sentences that you wouldn’t even notice if you were a white male, like ‘Please note there is no appeal process,’ might actually be a cue that says ‘We don’t think you’re going to make it,’” says Linos.

BIT trialed a reworded reminder email to applicants that was friendlier in tone. They added a sentence asking candidates to assess why they wanted to become a police officer, playing on results of research that African-American students perform better on tests after affirming their values when facing stereotype threat.

BIT’s intervention increased the probability that these candidates passed by more than 50%, effectively closing the gap between them and non-minorities.

“These studies show that we can make tweaks that actually have a meaningful impact as we think about the broader institutional reforms,” said Linos.

Anne Li Kringen, a criminal justice professor at the University of New Haven, suspects the application of these findings may encounter some resistance. “Entrenched in policing culture is this sense that ‘I shouldn’t have to hand-hold you through the process…If you self-select out, that’s your problem,” Kringen says. “This butts against the notion that if you want to become a police officer, you don’t need a nice email. You want to do it because it’s ingrained in who you are.”

In the US, black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people; 30% of black victims are unarmed, compared with 19% of white victims. A spate of police shootings, particularly in predominantly African-American areas with overwhelmingly white police forces, has made the issue of police force diversity a pressing concern (pdf).

“Few areas of 21st century policing need progressive ideas more than aggressively recruiting diversity,” police chief Fletcher says. Mayor Berke says he has been receiving calls from other cities across the country interested in working with BIT.

In Chattanooga, the BIT’s work was just one component of a larger strategy that also includes outreach at malls, expos, and colleges, said Wilson. “Because law enforcement all across the US is really not getting a good name right now to a certain extent, we have to do a lot more reaching out to the minority communities,” he said. “We go to the career fairs and they just walk by our tables.”

Linos acknowledges her work isn’t a silver bullet for reducing the diversity gap. But, she says, “while we’re thinking about broader institutional reforms, we also need to think about micro-behaviors, or those individual points in the [recruitment] process, where we can do better.” Over the next two years, BIT will be expanding trials to new cities, like South Bend, Indiana, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, and applying nudge theory to police-community relations more broadly. “We’ll have to replicate these trials in a lot more police forces to know for sure they work,” said Linos.