Birender Sangwan’s parents wanted him to be a doctor.

For two years, Sangwan even prepared for the medical entrance examinations in India before finally giving up. “I was always scared of hospitals,” he said in an interview at his modest two-room office at New Delhi’s Rohini court complex. “I still get dizzy and feel like vomiting when I go to hospitals.”

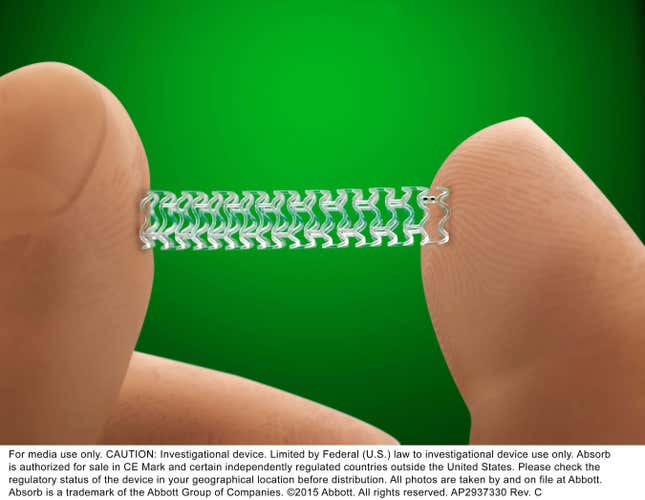

But in September 2014, he went to the Metro Hospital in Faridabad, a suburb of Delhi. A friend’s brother needed a coronary stent—a wire mesh planted in an artery to open up blood flow—fitted into his heart. The hospital charged his friend more than Rs1 lakh for this, without mentioning the device’s maximum retail price. “I asked the doctor to provide us with the purchase bill for the stent,” Sangwan said. “He refused.”

That refusal is the reason why 37-year-old Sangwan is at the centre of the storm sweeping through India’s Rs6.7 lakh crore ($100 billion) healthcare industry today.

A public interest litigation (PIL) filed by the affable lawyer in 2015 coaxed the Indian government to crack the whip on the country’s Rs3,300 crore ($531 million) coronary stent industry, ending years of rampant profiteering.

In a country where 30 million people suffer from cardiovascular problems and over two million die of heart attacks and strokes each year, stents have become essential. Every year, over 200,000 heart surgeries take place in the country. But this demand has stoked a racket of extraordinary proportions: Government data published last month showed that hospitals in Asia’s third-largest economy could be selling stents at margins of up to 654%.

Not any more, though.

On Feb. 13, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA), the primary agency for fixing drug prices, notified a price cap (pdf) of Rs7,260 for bare metal stents (those without any coatings) and Rs29,600 for modern drug eluting stents. The latter have a polymer coating, which gradually releases a drug to ensure that the blockage doesn’t reoccur.

So far, the average retail price for a bare metal stent was Rs45,000 ($671), while drug eluting stents were priced at around Rs1.20 lakh ($1790).

In a five-page order, the drug pricing authority explained that the move was made after an analysis of pricing data and extensive consultations.

During deliberations, it was found that huge unethical markups are charged at each stage in the supply chain of coronary stents, resulting in irrational, restrictive, and exorbitant prices in a failed market system driven by information asymmetry between the patient and doctors, pushing patients to financial misery; and whereas under such extraordinary circumstances, there is an urgent necessity, in public interest, to fix the ceiling price of coronary stents to bring respite to patients.

Lawyer turned crusader

Born into a middle class family in Kohala, Sangwan grew up in the nondescript Haryana village till he left for the capital to study political science at Delhi University. After graduating in political science, Sangwan turned to study law from Maharshi Dayanand University in Rohtak, Haryana.

In 2007, he enrolled as a lawyer at the Rohini court, where cases from the west and north-west districts of Delhi are heard. “For three years, it was a struggle, because I hardly knew anyone and it was tough to find cases. Most of the cases I attended to were criminal ones,” Sangwan said. Three years into the profession, he added civil cases and writ petitions to his repertoire. By 2013, he was handling PILs.

Then, in September 2014, Sangwan witnessed the Metro Hospital episode. “The total bill at the hospital was more than Rs3.2 lakh,” Sangwan said. “That is really expensive for a country like India.”

Soon, he filed a query under the Right to Information Act to find out the number of hospitals in Delhi that performed angioplasty. He found 54 such hospitals and the rates of stents varied across the facilities.

A month later, bothered by what he calls doctors’ brutality, Sangwan filed a complaint with India’s health ministry. In November 2014, Sangwan filed another RTI to see if stents came under the drugs category or metal category.

The crusade had begun.

The government responded in December, informing him that stents came under the Drug and Cosmetic Act, but weren’t covered under the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM). This list identifies medicines that must be made affordable for citizens. So, in February 2015, he filed a PIL at the Delhi high court (HC) to get stents included in NLEM. The court asked India’s chemical and fertiliser ministry—which oversees the department of pharmaceuticals—to take action.

There was no response for months. In October 2015, Sangwan filed a contempt notice at the HC citing the government’s laxity.

It was only in July 2016 that the Narendra Modi government notified the addition of stents in the NLEM. Sangwan wasn’t done, though. In December, he filed another PIL seeking a limit on the maximum retail price of stents. This was followed by a HC order asking the government to fix the rates. Finally, on Feb. 13, the government placed the cap.

“Our fight isn’t against the stent makers,” said Sangwan, “It is against the distributors and hospitals who have been extorting patients.”

Margin mania

“If you look at a distributor, it is a highly working capital intensive industry for two reason. One is the inventory, the other is the outstanding (payments),” explained Ganesh P Sabat, CEO of Sahajanand Medical Technologies, one of India’s dozen or so domestic stent manufacturers.

The situation, according to Sabat, looks something like this. If a distributor stocks between 120 and 200 stents per hospital, with each device priced at between Rs25,000 and Rs30,000, the working capital requirement is upwards of Rs30 lakh per hospital. It’s obviously a lot more for more expensive stents. On top of that, there’s a possibility of about 10% of the stocked stents become unusable after they cross their expiry date, and approximately 5% of stents have a chance of incurring some damage during transport or storage.

Alongside, there’s the issue of outstanding payments, particularly for government healthcare schemes, where the payout can take anything between six months and a year. All through, the distributor has to pay an interest rate of about 15%.

“Because the distributor makes this substantial investment in the working capital, they end up asking for 30-40% margins,” said Sabat, “And the hospital adds its own margin on top of the distributors.”

Sangwan, too, agrees that it isn’t the manufacturers who are inflating prices. “The manufacturers have been selling at the same price for years,” he said. “The distributors, hospitals, and doctors are hand in glove with each other and they are the ones making the money. The product should come directly from the manufacturers to the patients.”

India’s healthcare service providers cannot deny that such malpractices are rampant. To start with, only about 1% of the hospitals in the country are accredited, the rest are wont to flout norms and rules. Industry leaders, speaking on the condition of anonymity, argue that once accredited, the margins of bona fide healthcare service providers come under pressure because of the cost of following prescribed norms and putting in place the required systems. And with shrinking margins, hospitals come to increasingly rely on pharmacy sales, medical devices, and medical diagnostic testing. The cap on stent pricing, therefore, will hit their balance sheets further, unless it is made up for by increasing the overall cost of cardiac procedures that use such devices.

Industry heartburn

The drastic price revision has rattled India’s stent market, especially multinational medical device manufacturers with expensive offerings.

The Advanced Medical Technology Association (AdvaMed), a Washington DC-based trade association of over 300 medical technology firms, including stent makers Abbott and Boston Scientific, said it was “deeply disappointed” by the NPPA order. In a statement, AdvaMed explained:

While the intent is to cap prices in patient interest, this pricing has the potential to block innovations and limit access to world-class medical care and options to deserving patients. The singular focus on controlling ceiling price of stents, without attempting to address the larger picture and correct inefficiencies in the healthcare ecosystem will not achieve its stated benefit, in the long run.

The decision also disregards the evolution of coronary stents over the last four decades, and blocking innovation may set our healthcare sector back by at least a decade, when there were far lesser options for Indian patients. There is a clear, measurable difference between different types of stents and their benefits. The government should have taken this categorization into consideration before regulating prices.

In the days immediately following the NPPA order, reports suggested that Abbott’s bioresorbable stents (which fully dissolves over time), previously priced at Rs1.6 lakh, were withdrawn from a number of Mumbai hospitals. In Kolkata, too, high-end stents suddenly went out of circulation.

The company, however, denied that anything of that sort happened. “Abbott continues to market our full range of coronary stents available in India, per the NPPA order of Feb. 13, 2017,” a spokesperson said. “We have also advised trade partners and hospital partners to abide by the ceiling prices determined by the NPPA order.”

Some part of the setback for multinational stent manufacturers is of their own making, though.

Girdhar J Gyani, director general of the Association of Healthcare Providers, which represents over 400 hospitals nationwide, explained that companies were unable to make a solid case for the use of more expensive, advanced stents, as opposed to older, cheaper variants.

“Unfortunately, our cardiologist friends were not able to produce the validated report which says that the fifth or fourth generation stents will give better outcomes,” said Gyani. ”I wanted a very validated report but what I’ve been able to get are reports produced as marketing tools by the stent companies.”

Although the association supports the government’s move to cap some stents, Gyani argued that the NPPA order will make it difficult for patients to get top-of-the-line stents even if they want, and can afford, them. “Our final line is, please keep this option open for the patients who are affluent and who want fourth and fifth generation stents,” he said.

There’s also the fear that the pricing-cap on stents will drive away the lucrative wave of medical tourists who have been coming to Indian hospitals in growing numbers. “If we don’t give them the option, they may not want to come to us,” Gyani added. Well-heeled Indians, too, could fly overseas for treatment if the situation persists.

Indian stent-makers aren’t buying the argument. Their stents, they insist, are just as good as those of their foreign-made counterparts. “We can innovate much faster than them and we have more advanced features,” said Sabat. “With marketing and financial muscle, they try to show that they’re the most advanced.”

In any case, it’s not that multinational stent-makers can ignore India, said the managing director of another Indian firm, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Can any company neglect this population? No. We have 1.2 billion people,” he said. “Let’s see after a year how many patients really went out of India (for treatment).”

Sangwan, meanwhile, is raring for another fight, this time to bring down the prices of orthopaedic products, including those used in knee and hip replacement surgeries.

“I am also planning to do my PhD in law,” he said. “After all, I must fulfill my parents ambitions of me becoming a doctor.”