Game over for privacy-minded lemurs.

A new facial recognition system from George Washington University and Michigan State University, adapted from open-source software designed for human faces, claims up to 98% accuracy identifying specific lemurs. The research is an example of how open-source AI software, in this case facial recognition, can disrupt well-worn human systems, like zoological fieldwork, with relative ease.

Research on wild animals like lemurs has traditionally been a hands-on endeavor, the authors explain in the paper, published in BioMed Central Zoology. A team in the field would have to capture and tag lemurs for easy identification, or have worked with the animals enough to recognize them on sight. While a romantic notion, living among the lemurs “can be costly, time-consuming, and may be impractical for larger-scale, population-level studies,” the team writes.

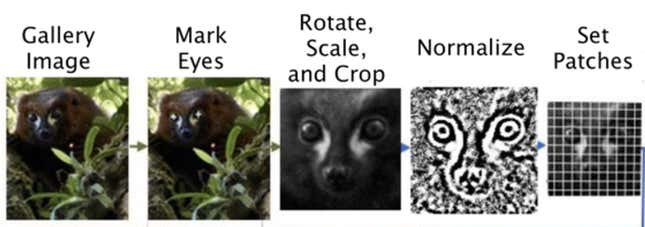

Instead, the researchers collected images of 80 red-bellied lemurs (a wild species in Madagascar), and used the images to train a modified version of the open-source facial recognition software OpenBR. The system uses facial traits like eye position to determine individuals. It doesn’t take coloration into consideration, however, because that can change between different lighting situations.

The data set was small—only about 460 images total—and researchers found that the way a lemur’s hair was matted down could change their facial appearance enough to deceive the algorithm.

Even with those limitations, the team reported 84-98% accuracy in tests that included scenarios with new lemurs the algorithm had never seen before. The paper notes that the system is intended for tracking the location and habits of a group of known animals.

Automating this work could streamline the study of other elusive animals like sloths, bears, or raccoons, according to the paper. This passive method of spying can reduce the risk of injury to animals and researchers; lower veterinary costs associated with capturing, sedating, and implanting trackers; and has the added bonus of sidestepping local regulation on how many animals can be captured for tagging.

“We would not recommend researchers become wholly reliant on computer programs for individual identification of study subjects, but training multiple researchers to accurately recognize hundreds of individuals is time-consuming and costly, as well as potentially unrealistic,” the George Washington and Michigan State team writes.