Two states in the US—Washington and Colorado—legalized recreational marijuana use this year. More than half of Americans now support legalizing marijuana, up 20 percentage points in the last decade. But the concept of legalizing drugs is not as radical and modern as it may seem. For thousands of years, most drugs, including marijuana, morphine, and cocaine, were produced, sold and consumed legally. It was not until the early 20th century, under an initiative led by American missionaries and temperance groups, that the concept of a global prohibition of drugs took hold. Even then, many countries, particularly drug-producing ones, were reluctant to embrace prohibition. Opponents predicted that criminalizing drug use would never eliminate demand and the cost of interdiction would fall disproportionately on them. They were right. The US and Europe should rethink their drug policy, not only marijuana but all other drugs too.

Prohibition of drugs has not been effective at eradicating their use. As the global drug trade continues to thrive, developing countries pay most of the price. The cost to them not only includes law enforcement, but the violence and corruption associated with the drug trade, which undermines economic development and keeps millions in poverty. A better use of resources would be to treat drugs as a health problem, and legalize and regulate the use and sale of drugs. That would probably make richer countries better, or at least no worse, off, and improve the lot of developing countries.

The US spends more than $40 billion each year on drug prohibition. But that is just the explicit cost. The implicit cost: increased violence, otherwise productive citizens in prison, and perpetual poverty, both at home and, especially, abroad. Countries mired by the violence and corruption associated with the drug trade might otherwise be viable trading partners, with the money spent on drug interdiction better spent on other means. According to the World Bank, at least three-fourths of expenditures on drugs in the US goes toward apprehending and punishing dealers and users; treatment expenditures account for, at most, a mere one-sixth of the total. That’s in spite of evidence that treatment programs are more effective and economical than interdiction.

Nonetheless, prohibition does decrease drug use. The World Bank estimates cocaine use would double if it became legal in America. Drugs can be dangerous and highly addictive, and there is concern that legalizing drugs would lead to a major public health crisis—but that is not necessarily the case. (Arguably, the real drug crisis in America revolves around legal, prescription drugs.) Legalization allows for a more nuanced approached than discouraging drug use through criminalizing possession and sales. For example, cocaine is often not addictive and users tend to be price sensitive. That means taxing cocaine may be an effective deterrent. Regulation can also ensure quality and that drug users get the product they want. Nobel Prize winning economist Gary Becker speculates that drug prohibition increases addiction because it makes users reluctant to seek out treatment.

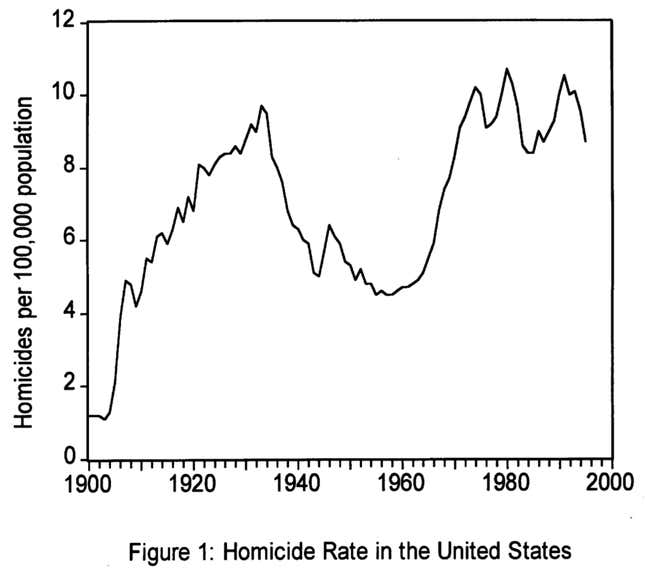

Trade in illegal drugs often results in violence because of the high margins for profit and inelastic demand from consumers (some users will pay almost anything). According to Becker, the more you enforce drug prohibition, the more violence you’ll see. That’s because more enforcement, or stricter punishment, drives up the price of drugs because there will be less supply. But demand will still exist so there’s more potential profit for large criminal organizations who have the resources, through corruption or large networks, to skirt the law. The higher profits and enhanced power of organized crime only increases the violence. This can be seen in the figure below from economist Jeffrey Miron plotting the US homicide rate in the 20th century. There is a noticeable increase during prohibition and again starting with the War on Drugs which began in 1971. Even after controlling for other factors: population, age, gun ownership, economic conditions, the incarceration rate, Miron found a positive correlation between the homicide rate and drug enforcement in America.

The drug trade tends to most adversely affect the poor. Research by economist Steve Levitt and sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh found drug gangs in America are often organized as elaborate pyramid schemes where most drug dealers barely make minimum wage, but are exposed to extreme violence. This is also true in drug-producing countries, but the profits are even smaller; 87% of the profits from the cocaine trade go toward the richer drug-consuming countries.

The illegal drug market favors organized crime in developing countries too, but this is especially true in poorer countries where criminal organizations often substitute for the government. Violence also often intensifies amid crackdowns on the drug trade in developing countries. But because drug cartels are often so powerful, the result can be far more destructive. Removing the head of a powerful drug cartel can upset the social order, undermining the semi-stable oligopoly that was in place. The cartel may be replaced by a multitude of warring factions vying for their share of the market. This can, in part, explain the increased violence in Mexico. After new enforcement tactics made it harder to transport drugs in the Caribbean Sea, much of the trafficking—90% of the cocaine bound for the US—moved through Mexico. Meanwhile, the traditional head of the Mexican drug trade, Felix Galladro, was captured in 1989. This prompted competing cartels to engage in violence to claim their share of the growing drug trade. In spite of this, Mexico has made great progress in terms of economic development and now has a large burgeoning middle class. But as long as drug violence persists, Mexico will struggle to join the ranks of fully developed economies. The World Bank estimates that organized crime cost Guatemala 7% of GDP in 2005 and large-scale civil conflict costs the average developing country 30 years of GDP growth.

The Colombian government has been effective at reducing the drug trade and violence within its borders. But because the demand for drugs still exists, Colombia has merely pushed drug trafficking to its neighbors, often to weaker governments who may have ties to terrorism. Indeed, the more enforcement there is, the more drug trafficking will move to weaker and failing countries.

Legalization changes the equation. Taking the drug trade out of the shadows will be a game-changer for farmers in developing countries who grow drug crops. Either they’ll face more global competition, which will drive down prices and may force them to start growing something else. Or, existing farmers will establish a comparative advantage in the cultivation of drug crops, similar to grape farmers in the Champagne region of France, and they’ll take a higher share of the profits with more security. Citizens of vulnerable countries who don’t participate in the drug trade will also benefit. If drug production and trade were legal, contracts and property rights would be enforceable under law instead of violence, and drug-producing countries could tax drug exports and put the revenue toward economic development.

Even if it’s in their best interest to legalize the drug trade, developing countries can’t make production legal without the cooperation of the advanced economies who form the bulk of their market. They can’t defy the laws of richer countries whom they depend on for other areas of trade and aid. Individual countries or states changing their laws won’t have much impact either. The market is broken and requires comprehensive and coordinated reform. Legalizing marijuana use is a step in the right direction, but unless the production and sale of it and other drugs are legal and regulated, not much will change for those who pay the price for the war on drugs.