Tests of ideology—beloved by Mao and Stalin—are heading toward reality on university campuses

Universities may be—or at least pretend to be—politically neutral. Their staff rooms sure aren’t.

Universities may be—or at least pretend to be—politically neutral. Their staff rooms sure aren’t.

Under the rising but already controversy-laden administration of US president Donald Trump, and in the wake of other global political shake-ups in the past year such as Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, faculty members at universities are in a mood to speak their minds like never before. But highly educated professors tend to be highly partisan, and the sharp divides of ideology aren’t sitting well with either side.

Take this clash as a leading example, from England: At the University of Sussex, a professor held a workshop for staff on “dealing with right-wing attitudes and politics in the classroom.” The event was immediately condemned as what some saw as an attempt to restrict free speech. It happened right after one survey of British universities claimed that nine out of 10 schools in the UK have restricted free speech in some way.

The anti-free-speech argument has also been made by conservative professors in the US to attack liberal professors and students at the University of California, Berkeley, where protests shut down a planned appearance from alt-right leader Milo Yiannopoulos earlier this month.

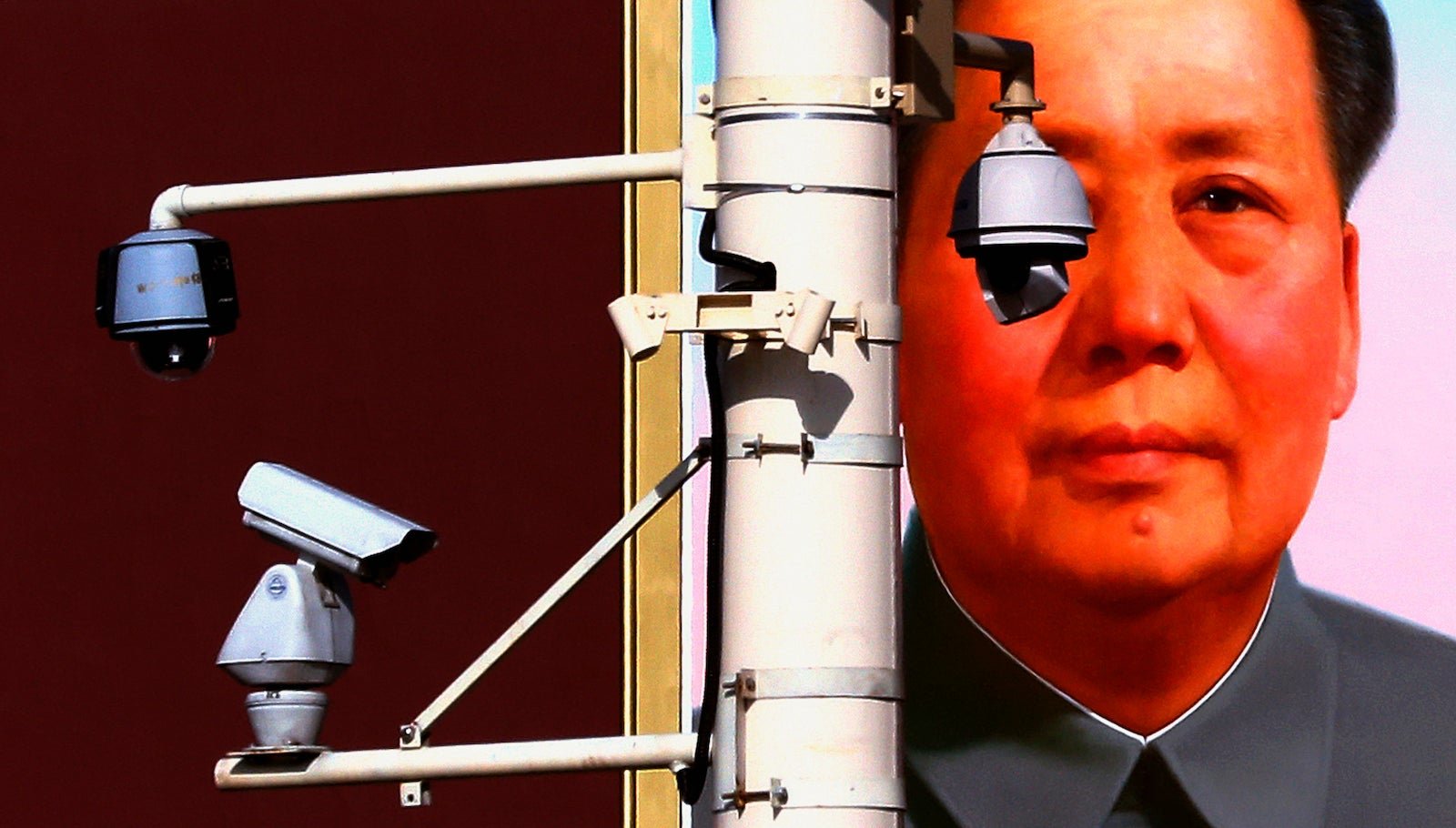

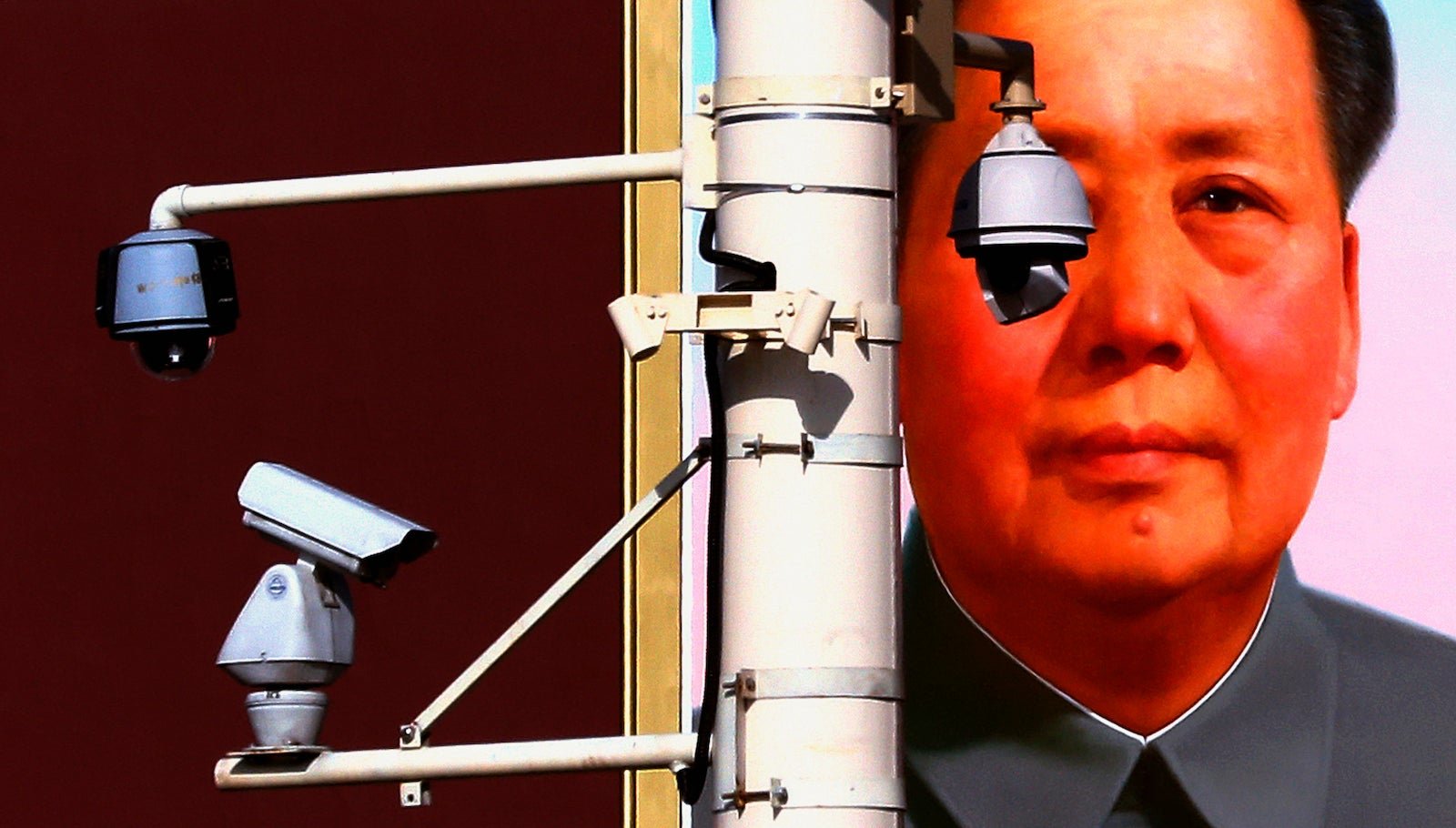

Tensions are now at a point where actual tests of political ideology are being proposed, the likes of which were once famously favored by dictators Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong—in the latter’s Cultural Revolution, for example, Chinese universities “used class background and ideological purity as criteria for admission” (pdf).

This week, a conservative state senator in Iowa put forth a bill that would let the US state’s universities cherry-pick their teachers based on their political preferences. Per Republican Mark Chelgren’s bill:

A person shall not be hired as a professor instructor member of the faculty at such an institution if the person’s political party affiliation on the date of hire would cause the percentage of the faculty belonging to one political party to exceed by ten percent the percentage of the faculty belonging to the other political party.

Chelgren calls it a way to create “partisan balance.” Others, particularly Democrats in Iowa, see it as a dangerous path toward potential Soviet-style purges of university faculty ranks. Under the bill, the state would provide voter registration lists for colleges to pair with applications to teaching positions. “It is outright fascist,” says one critic.

The bill has gone viral in the US, drawing uproar from professors and students on liberal campuses.

But the thinking behind it is not entirely unreasonable. America’s institutions of higher education skew overwhelmingly liberal, and the idea of balancing a bubble of leftist thought with more viewpoints from the other side is one that could have enormous benefit inside and outside of the classroom.

The idea of achieving that balance by imposing ideological litmus tests with legislation, though—that’s a separate matter.