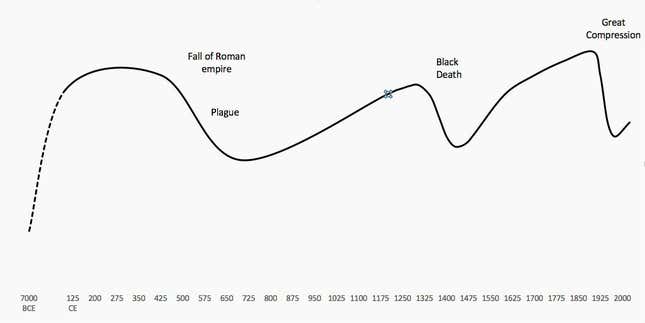

How do you solve a problem like inequality? Economic policymakers have been grappling with this for a long time, with varying degrees of urgency. The search for solutions has become increasingly serious since the 1980s, when inequality began rising again, recently reaching historic highs.

But the problem has been solved before.

After studying thousands of years of human history, Stanford professor Walter Scheidel identified four indisputable ways to reduce inequality: war, revolution, state collapse, and deadly pandemics. These “four horsemen,” as Scheidel dubs them in The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century (Princeton University Press), have proven far more effective at reversing inequality than more peaceful efforts, like improving education, or non-violent shocks, like financial crises.

Today’s levels of inequality aren’t unprecedented, Scheidel notes. The share of income owned by the wealthiest Americans has only recently risen to levels last seen in 1929. In the UK, the richest 10% held more than 90% of all private wealth before the First World War; today, it’s a little more than half.

This suggests that the inequality seen today has the scope to become far more extreme. Globalization, aging populations, and immigration all contribute to inequality by diverting public services away from redistributive policies. What’s more, new technologies and widespread automation will further widen the gulf between high-skilled and low-skilled workers.

Addressing the high levels of inequality in the US, UK, and elsewhere requires radical policy changes, Scheidel says. And the only time those policies led to a meaningful “leveling” in the past was in the aftermath of catastrophes.

Scheidel spoke to Quartz from New York about the long history of inequality. The conversation has been edited and condensed.

Quartz: Past periods of reduced inequality were preceded by catastrophe. How does something so destructive—the “four horsemen” you describe in the book—produce anything positive?

Scheidel: The first one is mass-mobilization warfare and the classic examples are World War One and World War Two. A very large share of the population got drafted into military service, while the civilian labor force also became fully mobilized for the war effort.

A strong nation state was needed to organize the war effort and tax rates went up to extremely high levels on the rich—90% in some cases—to pay for it. Capital lost value because of government interventions and physical destruction, particularly in Europe. Meanwhile, there’s massive redistribution to workers. Then there’s the knock on effects on democracy. Voting rights, membership in trade unions, etcetera. All these things really surged around these wars because governments have to offer the people something in return.

The second, in a sense, is a no brainer: it’s transformative revolution. If you are Lenin or Mao and you go out in Russia or China and expropriate all the rich, often killing them in the process, and nationalize everything, you plan an economy where you set all the wages and all the prices. That’s an extremely invasive process but if you are only interested in equality that’s a very quick way of doing it.

And the others?

The other two are more common in the distant past: state collapse and epidemics. State failure is an even less desirable way of leveling compared to the others because everyone is objectively poorer—it’s just the differences are wiped out. When the Romans incorporated Britain into their empire there was a massive increase in inequality, but then it falls apart in the 5th century. The Anglo-Saxons come in and all of a sudden you are back to where you were before.

Finally, there are massive epidemics that sweep in and kill a really large share of the population, like the Black Death in medieval Europe. It doesn’t destroy the physical infrastructure—the land or capital—so there is a fundamental reset in the value of labor. Workers can ask for higher wages and the employers’—the capitalists’—assets lose value.

Could any of these can happen again now, and have a similar impact on inequality?

Thanks to technological change, the style of warfare has really moved on. Instead of intense mobilizations that were possible 50 or 100 years ago, you’d have a quick, high-tech war. It could be very expensive and disruptive but it wouldn’t necessarily produce the same effects on inequality. Overall, the whole world has become more peaceful for any number of reasons. The same is true for transformative revolution. Most people have little desire to repeat what happened in the big communist countries earlier in the 20th century.

Could we see revolution coming from populist movements on the right instead?

They would be more bourgeois; it wouldn’t necessarily be overtly redistributive. You could give the example of the Nazi takeover or revolution but, there was no real interest in bringing about greater equality beyond the rhetoric.

Massive epidemics, though, still seem possible, after Ebola, Zika, and with general fears of biological warfare.

Plagues worked really well in an agrarian society, but modern economies are so interconnected and sophisticated that if you randomly killed just 10% of all people it might cause real damage and destabilize the entire system. But it wouldn’t necessarily have the same distributional effect for workers as it has in the past. One option that exists now that didn’t in the past is more automation. If there was a big plague you’d build more robots and you might have more inequality in the long run.

So if these four ways have historically been the only effective means of reducing inequality, and they are both undesirable and less “effective” than they once were, where do we go from here?

That’s exactly the question. Today people like Trump in the US and populists in Europe say, to various degrees, “look what things were like 40 years ago, let’s make sure we go back to that.” They are implicitly going back to this post-war period when you had economic growth, an expanding middle class, low inequality, and everything was great. And it’s true, it’s a very desirable state of affairs. But look at the policies, the taxes and tariffs, and unions. All this arose in a very specific context. Policymakers, advocates, and academics have to think harder to develop more noble ways to reduce inequality that might work today.

Has anyone come up with policies that are both effective and realistic?

In the US and UK inequality has risen so much that policies which could be implemented would only produce improvements at the margins. Famously, the late Tony Atkinson wrote a book—Inequality: What Can Be Done?—and he tried to price the cost of these policies. He’s the only one I know who tried to do this in a careful way. It showed improvements are possible but only up to a point. The more radical measures become, the costlier they are and the less likely they will be implemented because of the politics.

How much worse can now inequality get, then, if there isn’t the political will or the financial resources to address it?

Inequality can’t go up indefinitely. There has to be some kind of limit—we just don’t know where it is. If you operate in a globalized economy where there are so many ways of obtaining resources from other countries, or parking your assets in other countries, then there is the potential for extreme inequality, especially at the very top of the distribution, like we haven’t seen before.

Your book suggests this extreme inequality could lead to a class of “superhumans.”

This hasn’t quite happened yet, but if you talk to geneticists we’re on that trajectory. It’s already well known that some of the boldest or ethically questionable experiments have been undertaken in East Asia, and there’s a great potential for that continuing. A couple of decades down the line and it might be possible for parents to create designer babies. If that were ever to happen, you could end up with an upper class that is genuinely different from everybody else. It doesn’t just have to be genetics; many people are working on implants that will enhance your capabilities.

I live in Silicon Valley, where all these people talk about living to be 1,000 years old. It’s probably not going to happen any time soon, but it shows that the will exists.

That’s a troubling future. I’m not surprised, given the subject of your book, but it seems like this interview won’t end on a hopeful note.

There is certainly room for hope, but what is unlikely to happen is a really substantial equalization, the way it happened earlier in the 20th century.