To understand the war on the global elites that Steve Bannon and Donald Trump claim to have unleashed, think of an epic battle between Bruce Wayne and Lex Luthor.

The fabulously wealthy corporate titan and criminal mastermind, Luthor is motivated by self-enrichment and megalomania. Originally drawn as a man with a full head of red hair, Luthor’s hatred of Superman and Batman may lay partly in a complicated hair story variously interpreted as an artistic mistake, Superboy’s fault, or merely male pattern baldness. As a child he was either an abused boy growing up in poverty and bootstrapping his way to wealth, or as the resentful son of a wealthy and domineering father. Luthor blames Superman for his failures to help humankind and the chances he has passed up to do the right thing. His arsenal of dastardly plots includes unleashing chaos in Europe and allowing aliens to destroy Topeka, Kansas. Oh, and he eventually becomes president of the United States.

The man behind the Batman mask is a fabulously wealthy philanthropist from old wealth; he has a dark side that gives him compassion for outsiders and victims of injustice. Though sometimes portrayed as a playboy, Wayne is discreet about his private life and well-behaved in public. A scientific and analytical person who derives his powers from technology and an array of surrogates, he has traveled the world and sees his mission as making it a better place. But despite his do-gooderism, Gotham remains a dangerous place with huge gaps between the rich and poor—and an unspoken reality is that Batman’s existence is enabled by the very wealth that helped to create those gaps.

This juxtaposition of Luthor and Wayne maps uncannily well on to the battle lines that the Trump administration and his chief strategist, Steve Bannon, have drawn against the so-called global elite.

Trump ran on his claim to be a billionaire and successful businessman and the power of the gaudy, nouveau-riche Trump brand. His philanthropy has been shown to be modest at best, often self-serving—like paying $20,000 for a painting of himself—and at times illegal.

Trump’s wealth started with a supersized inheritance, but Bannon’s childhood was in a working class family, and his wealth was self-made. Nevertheless, Bannon’s background has the trappings of the elites despite his self-professed “virulently anti-establishment” views: he went to Harvard Business School, was an investment banker at Goldman Sachs, and made a mint by investing in Seinfeld. He has described himself as an economic nationalist, hardly surprising given the content he supported at Breitbart News. He has excoriated crony capitalists and the bailouts of investment banks “and their stooges on Capitol Hill.” Multiple accounts have described the rage he felt over the impact of the 2008 financial crisis on his family—paradoxical, given the way Trump is filling Washington with crony capitalism and loosening the rules intended to prevent another bank bust.

Bannon has made no secret of his intentions to upend the system. His wrath includes old-style Republicans and conservatives as well: Paul Ryan, the Heritage Foundation, William Kristol, and pretty much all of the Republican Old Guard—the “party of Davos,” in Bannon’s words.

Combined, this makes for a very Luthorian narrative. But in the alternate universe of 2017, Bannon and Trump have managed to channel populist rage toward billionaires and CEOs of multi-national corporations: the Davos class, in shorthand.

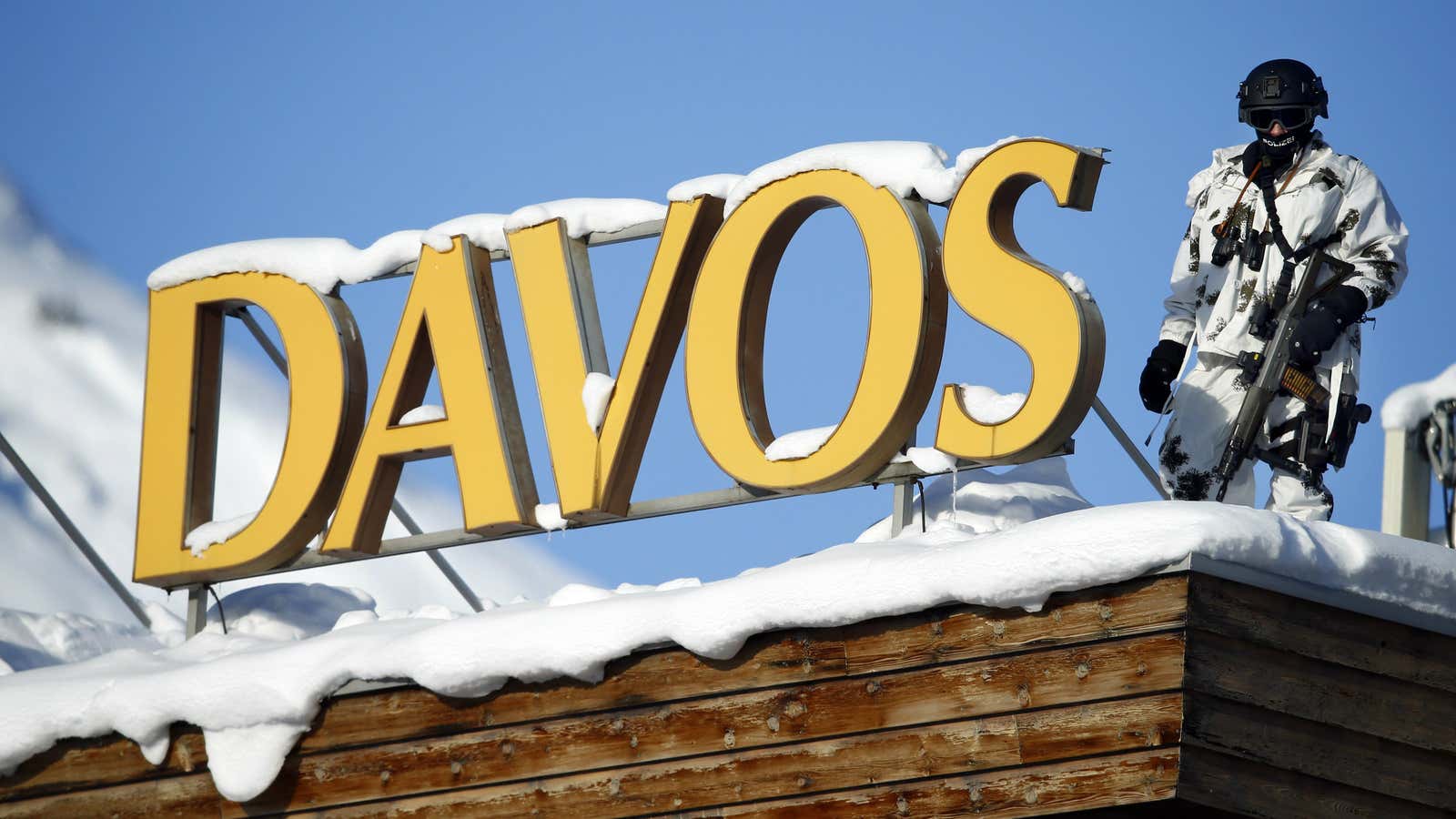

Davos, of course, is the resort town in the Swiss Alps where the World Economic Forum holds its annual meeting of roughly 3,000 business, government, media, academic, and non-profit leaders, with a few celebrities mingling about.

The annual media frenzy of attacks on Davos took on an extra edge this January in the aftermath of the Brexit vote and the US elections. It was open season for the left, right, and center. Naomi Klein lay down the gantlet with a scathing and widely shared piece in The Guardian blaming neoliberalism and “the Davos class”—in which she solidly placed Hillary Clinton—for the rise of Trump.

This Davos class includes the likes of Microsoft founder Bill Gates, Virgin Atlantic mogul Sir Richard Branson, and Alibaba founder Jack Ma, and of course George Soros, the bogeyman of the far right. In other words, do-gooder billionaires—the Wayne-type progressive capitalists that Chrystia Freeland, now Canada’s Trade Minister, wrote about in her book Plutocrats; and that Matthew Bishop and Michael Green describe in Philanthrocapitalism—the earnest do-gooders who talk about “improving the state of the world,” even as they bask in privilege.

I’m nowhere close to being a billionaire, but I have attended Davos twice as a member of the Forum of Young Global Leaders and as a think tank executive, and have even spoken there. I’ve sipped champagne at the Belvedere Hotel and bumped elbows with celebrities on the ride up the slope of Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain. I know first-hand the incongruity between the exclusivity of the event and the conversations about how to make the world a better, more inclusive place.

To be sure, the Trump team itself includes denizens of Davos, though perhaps grudgingly. Bloomberg dubbed the only Trump team member to attend this year’s Davos, Anthony Scaramucci, “this year’s surprise Davos star.” Scaramucci returned to DC to find himself out of the senior White House job he had been promised and Apprentice reality television villain Omarosa Manigault angling for his office.

And not-insignificant Davos attendees, bankers in particular, are also Trump confidants, or at least confident in his plans to boost growth. Four Trump cabinet nominees have attended Davos before, including Rex Tillerson, Robert Lighthizer, and Elaine Chao. The fourth is Rick Perry, to whom I was introduced at a Davos lounge after some colleagues and I met with a progressive Iranian iman—the kind of person whom the new administration apparently does not believe exists.

The media slammed the Davos crowd particularly hard for having dismissed Trump and Brexit a year ago. But the World Economic Forum did get at least one closely related thing right: for the past few years, income inequality and the resulting social and political unrest has been high on its annual list of the most impactful and likely global risks.

The Forum has been prescient on other issues as well—like the impact of artificial intelligence and 3-D printing on jobs and society—issues that represent a far bigger threat to working class jobs than migration or trade.

Professor Klaus Schwab, the World Economic Forum’s founder, was criticizing globalization back in 1996: “In the famous process of ‘creative destruction,’ only the ‘destruction’ part seems to be operating for the time being.” He recommended a menu of policy options, which have since been discussed mightily: training and education, telecommunication and transportation infrastructure upgrades, incentives for entrepreneurs, and new social policies to support the losers in globalization.

In other words, he recommended the very policies that Bannon’s stated nemesis, the Republican establishment, has pushed to prevent and for which, aside from infrastructure, Trump has shown little inclination.

So why have Trump and Bannon been so successful in painting the Davos class as the villain?

Talking about how to improve the world sets up well-meaning global elites for accusations of hypocrisy and criticisms that they have not made more progress. Take, for example, the World Economic Forum’s worthy work toward achieving gender parity even as it is perpetually criticized for the underrepresentation of women at events. In 2014, I was one of only 15% of Davos delegates who were women. That number is above 20% this year, still low if moving in the right direction.

Precisely because the World Economic Forum is not a monolithic voice, the organization as a whole is vulnerable to the actions and words of any participants out of step with the forum’s lofty intentions, and to charges of greenwashing or posturing. And, presto, Trump’s base doesn’t believe “the elites” any more than it believes in mainstream media.

It’s entirely possible that the images of the philanthrocapitalists and progressive plutocrats would come off better if they were less visible. But I don’t think the world would be better off if they weren’t having these conversations.

Davos thus is the perfect foil that lets Trump and Bannon blame both the 1% and the bottom 50% for the plight of America’s white working class. The incomes of these two groups has risen dramatically along with globalization, even as the incomes of roughly the 51st through 80th percentiles fell, as illustrated by Branko Milanovic’s now-famous elephant chart.

Politicians have always redirected public anger toward those below their base rather than those above. That’s why Trump’s anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-minority message resonated so strongly with his mostly white base. And cosmopolitan elites, by extension, are tarred with the same brush.

Middle class Americans consistently approve of tax cuts that disproportionately benefit the very wealthiest in part because they aspire to the same, no matter how unrealistically. It’s easier to blame someone in worse straits than someone whose lifestyle you wish to enjoy some day. So some elites get a practically free pass.

By attacking those other elites, Bannon and Trump hedge their bets. They buy the complicity of “their” uber-rich by offering them tax cuts and cabinet positions. Meanwhile, the Trump political base remains willfully blind to the corrupt practices that, before the election, they claimed to despise.

The message of the Davos class is optimistic, based on the idea of cooperation and the idea that a global pie is bigger and means bigger slices for everyone. I support this view of globalization but also believe that both businesses and governments need to do more for those who feel they have been left behind.

The Bannons and Trumps of the world are fundamentally pessimistic and want a bigger slice of a smaller pie. Trump and Bannon have tapped into a vein of legitimate discontent and twisted it for their own purposes. Their attacks on the Davos crowd focus attention away from where it ought to be—on Luthor’s, er, Trump and Bannon’s, plans.

Trump claims he wants to upend the old order, but his policies so far are focused on protecting it—certainly in the areas of fossil fuels and banking. Trump sells clothing made in China and profits from a global business empire, all the while criticizing corruption and crony capitalism. The only thing Trump and Bannon are really targeting is who’s in control.

In the end, Bannon and Trump against the global elites is a battle of nihilism versus the hard slog of messy, uneven, and complicated change. It’s the unbridled rage of Breitbart versus the understated (and sometimes soporific) tolerance of National Public Radio and the BBC. It’s the old economy versus the new economy.

The difference between these battling elite worldviews is as stark as night and day, as disparate as the characters of Luthor and Wayne. Our superhero stories are a parable for the real world. Will Lex Luthor or Bruce Wayne prevail?

Spoiler alert: Given the number of “Golden Raspberry” nominations the 2016 movie Batman versus Superman received, I don’t think I’m doing anyone a disservice here. The film ends with Lex Luthor’s son, also named Lex Luthor (not to stretch the metaphor too far, but….) in prison and Bruce Wayne vowing to protect the world, but through plans with decidedly dark overtones.