It’s been six weeks to the day since Apple set records with the biggest corporate bond issue ever. The $17 billion worth of bonds of varying maturities were oversubscribed by a factor of three. Investors loved the mix of security and, at the time, decent rates.

It’s pretty obvious why companies—not just Apple—were rushing to issue bonds: Rates were around historic lows, allowing them to borrow incredibly cheaply. Apple’s 30-year bonds were issued at just 3.85% per year on a day when Treasury notes were going at 2.88%.

The problem with historically low interest rates, of course, is that they can’t stay that low forever. In the past few weeks there have been several encouraging signals for the American economy. Employment figures beat expectations in April and May. Ben Bernanke suggested the Fed might take it easy on quantitative easing “in the next few meetings.” Even S&P seems to believe the US is improving. All this is reflected in expectations that the Fed will soon let interest rates rise, which has led to higher yields and lower prices (yields and prices move in opposite directions) on US Treasurys, and, correspondingly, on corporate bonds.

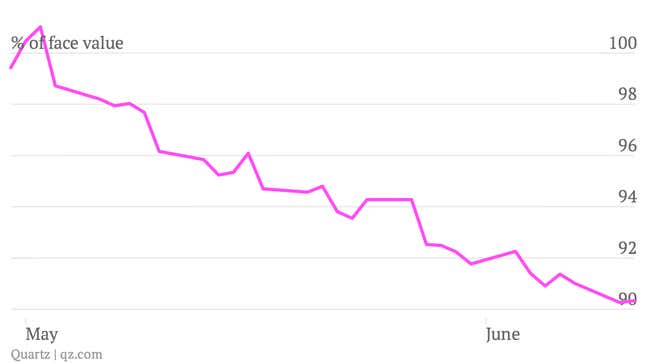

None of which is a big deal for anybody who plans to hold the 30-year bonds for 30 years. But for everybody else, that means they can’t get rid of the stuff fast enough: The price of Apple’s 30-year bonds—long term bonds are most sensitive to rising rates—has fallen to 90.33% of their face value, or par in bondspeak. We don’t think the bond rout will last, but for the time being, those other two-thirds of wannabe Apple bond-buyers must be pretty pleased with themselves.