Let’s be clear: The transgender people currently entangled in America’s so-called “bathroom bill” debates aren’t asking for all of the US’s restrooms to be redesigned.

“They’re fighting for the right and dignity to use the restroom that they feel matches their gender identity,” says Maxwell Ng, an architectural designer at DiMella Shaffer in Boston and chair of the steering committee for the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition.

But the debate has raised some interesting questions for designers. If there was an easy way to make restrooms more functional (technically “bathrooms” have baths in them), why not explore it? As Matt Nardella, architect at Moss Design in Chicago, notes, “We can design restrooms in such a way that people of all genders feel safe. There is a better way.”

So what does that better way look like? “It’s a little bit like the Wild West out there,” says Ng. “Nothing’s been codified as far as best practices go.”

The biggest culprits are building codes that mandate sex-segregated restrooms, but some of those are being revised. The goal may be unisex, but there’s no “one size fits all” approach. “There are hundreds of small decisions that can make things more open,” says Stephen Cassell, principal at Architecture Research Office (ARO), who designed gender-neutral restrooms for Congregation Beit Simchat Torah in New York City.

Importantly, unisex restrooms already exist. They have quietly become more common in the benign, non-politicized form of “family bathrooms,” which are popular in high-traffic spots like airports and highway rest areas. These are full-service, wheelchair-accessible separate rooms with sinks, toilets, and changing tables. “The family bathroom was born out of necessity when fathers with young daughters didn’t want to bring their daughters to the men’s room, or mothers didn’t want to bring their sons,” says Ng. Family-style restrooms solve many of the problems we’re facing today, even if they are difficult to scale in high-traffic areas. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

The new multi-user, all-gender template

One way to create a practical, trans-friendly restroom is to divide each stall into a separate chamber. Ng points to Google’s offices in Cambridge, where he saw eight stalls: four rooms flanking a corridor, each with its own toilet, sink, and changing table. They were all identical with one common mirror in the hallway. “I found that to be incredibly utilitarian,” he says.

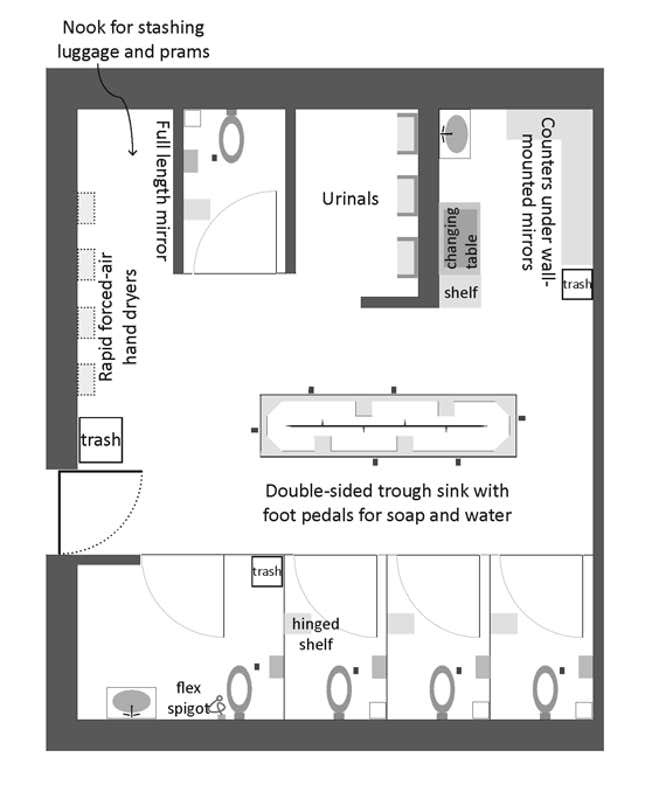

A similar plan was drawn up by Laura Norén, an ethnographer at NYU’s Center for Data Science and the co-editor of the book Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing. Norén’s ideal gender-neutral restroom looks like some of what’s out there today: An open line of common sinks and mirrors, with full-door stalls arranged along one or more walls. Unlike many other designs, she has included a separate section in the space for urinals, which she says can create a default gendered space within the restroom for those who want it. Urinals are also ”better for the environment and they’re faster,” says Norén, noting that entering a stall, closing the door and sitting down requires a time-consuming three-point turn. It also reduces the pee-on-the-seat situation (as least from cisgender men).

Today, most same-sex restrooms have stalls constructed out of durable (and expensive) materials like powder-coated stainless steel. In this model, the doors and walls are usually only tall enough to cover someone from the calves up. There are advantages to this design, such as being able to see if the stall is occupied, or if someone is having a health emergency. But full-length doors offer a self-contained experience and privacy within a larger shared space. As Cassell points out, “They also offer acoustic privacy,” and hopefully some olfactory privacy too. Another advantage of full-length doors is that “the cost of the actual partitions in multi-stall restrooms are very expensive,” says Nardella. “If we can build them out of wood, drywall, or tile, it’s less expensive than building partitions that don’t give privacy, and they take up less room.”

Another small tweak that can make a big difference has to do with functional décor. “A lot of transitioning people don’t want to do their makeup or adjust their clothes in the public parts of bathrooms,” says Cassell. “We want to make sure they have safe places to do that.” A mirror within the stall provides that option, but common mirrors in shared spaces should still remain.

In the ideal unisex restroom (and the most flexible budget), some stalls will have it all: a urinal, a toilet, a shelf for your phone (“So you won’t drop it into the toilet,” says Norén), a nursing chair, a mirror, and fixtures for wheelchair accessibility.

Larger establishments should be able to offer a mix of multi-user restrooms and some standalone rooms. Norén advocates keeping urinals in the larger unisex restroom, but cordoning them off to one side, perhaps with a privacy wall. “The urinals can direct a kind of gender division within the room,” she says.

The return of the powder room

Designers also should think about the areas where people wait for access to stalls, says Nardella, such as creating anterooms or the powder rooms of yore, but for all genders.

“The waiting area in our scenario becomes a public gathering place for men and women, which makes it inherently safer; there are more eyes on this waiting space,” he says. It also provides more incentive to make those anterooms into welcoming, well-designed spaces. “You’re not just putting in toilets and changing the signage,” says Cassell. “You want people to have a good experience.”

Sending the right sign

How do we advertise that a space is friendly to people of all gender identities? The pants/skirt divide so typical of restroom signage has long felt out of date, anyway. Graphic designers have already created several icons that communicate gender inclusivity, including a figure with pants on one side and a skirt on the other, or a picture of a commode above the words “all-gender restroom.” Then there’s the classic male and female figures with the words: “We don’t care.” Cassell has also seen signage with directions. “It asks everyone not to comment on people’s gender, looks or dress inside,” he says.

Sam Killerman, a graphic designer and the author of A Guide to Gender, has even created what he calls an inclusive, uncopyrighted, easily identifiable sign for gender-netural restrooms. It’s an image of a toilet. Simple, yes, but it says a lot by saying so little.

Bringing restrooms to the forefront, literally

Restrooms aren’t normally given prime positions in building planning. “There’s a tendency in architecture where bathrooms get the least thought; you just work by code,” says Cassell. This is a problem on multiple levels and contributes to a lack of interest in their design. Then there are the safety concerns. As Nardella notes, “Usually they end up in the back corner of the building, the least safe part. No one is there to see them, monitor them. We should be asking: How can we make them appear better so we can integrate them into the rest of the building’s public space?” If they’re beautiful spaces, with welcoming anterooms, there’s no need to tuck them away.

* * *

Ultimately, these changes are relatively simple to conceptualize. And while there is value in same-gendered spaces, expanding unisex restrooms offers safety and protection to far more than just transgender people—from the mom who doesn’t want to send her 8-year-old into the men’s room alone to an elderly person who might need a caretaker of the opposite gender’s help when using the facilities. In this way, unisex restrooms address a whole host of demographic changes and design problems.

“This is just better design,” Nardella says. “Better for everyone.”