Boycotting Mexican shrimp could be our last chance to save this tiny, endangered porpoise

The vaquita porpoise is an adorable but elusive creature. The smallest of cetaceans at just four or five feet long, the friendly-looking mammals swim exclusively in the Gulf of California, off Mexico’s Pacific coast. It’s also the most endangered species of porpoise: In 2014, biologists estimated there were just 97 individuals left in the wild, and the population has declined by a precipitous 40% each year since then. This year, the US Navy started training dolphins to locate the last two or three dozen surviving vaquitas, with the goal of relocating and breeding them in captivity. A group of international conservation advocates had decided that keeping the species alive in captivity—a practice that many marine mammal advocates disdain as cruel—was preferable to letting it die out in the wild.

The vaquita porpoise is an adorable but elusive creature. The smallest of cetaceans at just four or five feet long, the friendly-looking mammals swim exclusively in the Gulf of California, off Mexico’s Pacific coast. It’s also the most endangered species of porpoise: In 2014, biologists estimated there were just 97 individuals left in the wild, and the population has declined by a precipitous 40% each year since then. This year, the US Navy started training dolphins to locate the last two or three dozen surviving vaquitas, with the goal of relocating and breeding them in captivity. A group of international conservation advocates had decided that keeping the species alive in captivity—a practice that many marine mammal advocates disdain as cruel—was preferable to letting it die out in the wild.

It’s no mystery why vaquitas are vanishing. The porpoises keep getting killed by fishermen using gill nets throughout their home waters in the Gulf of California. Now a coalition of more than 50 conservation groups is urging consumers to boycott Mexican shrimp as a last resort for saving vaquitas from extinction.

“This is the vaquita’s very last chance,” said Sarah Uhlemann, international program director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “For decades, Mexican officials have failed the vaquita, and now only the strongest of actions will get their attention. To save these wonderful little porpoises, we have to boycott Mexican shrimp.”

For decades, fishermen have been casting gill nets in the Gulf of California to catch jumbo blue shrimp. These nets are practically invisible to vaquitas, which swim into them blindly and then find themselves unable to get away or reach the water’s surface. Like humans, porpoises (and dolphins and whales) cannot breathe underwater. If a porpoise gets trapped in a net, it drowns—and becomes “bycatch,” a superfluous and frequently unvalued part of a fisherman’s haul.

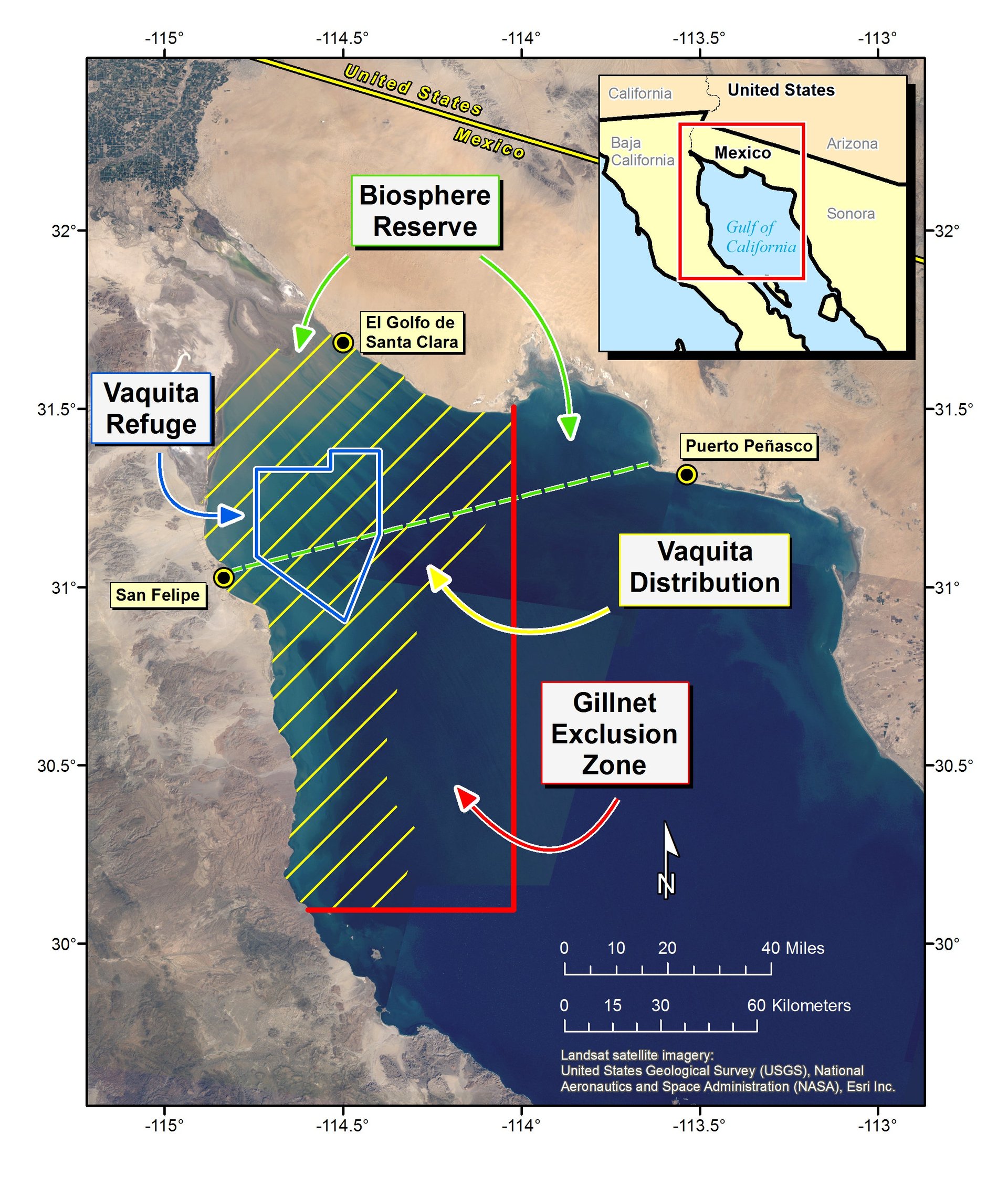

In 2005, well aware that these nets were killing vaquitas, Mexico established a small vaquita refuge in the area where all commercial fishing was off-limits. Ten years later, in 2015, bowing to pressure from conservationists who noted that the vaquita population had been nearly wiped out, Mexico established a two-year ban on gill nets throughout the vaquita’s entire range in the tiny northern section of the Gulf of California.

But according to conservation advocates, enforcement of that ban—which expires next month—has been dismal. “Mexico’s half-hearted baby steps are wiping the vaquita out,” said Zak Smith, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council. ”The lives of vaquita are in the hands of people who’ve known for years that their actions are driving this species to extinction,” he added, citing “the Mexican government, shrimp fisheries and U.S. seafood importers.”

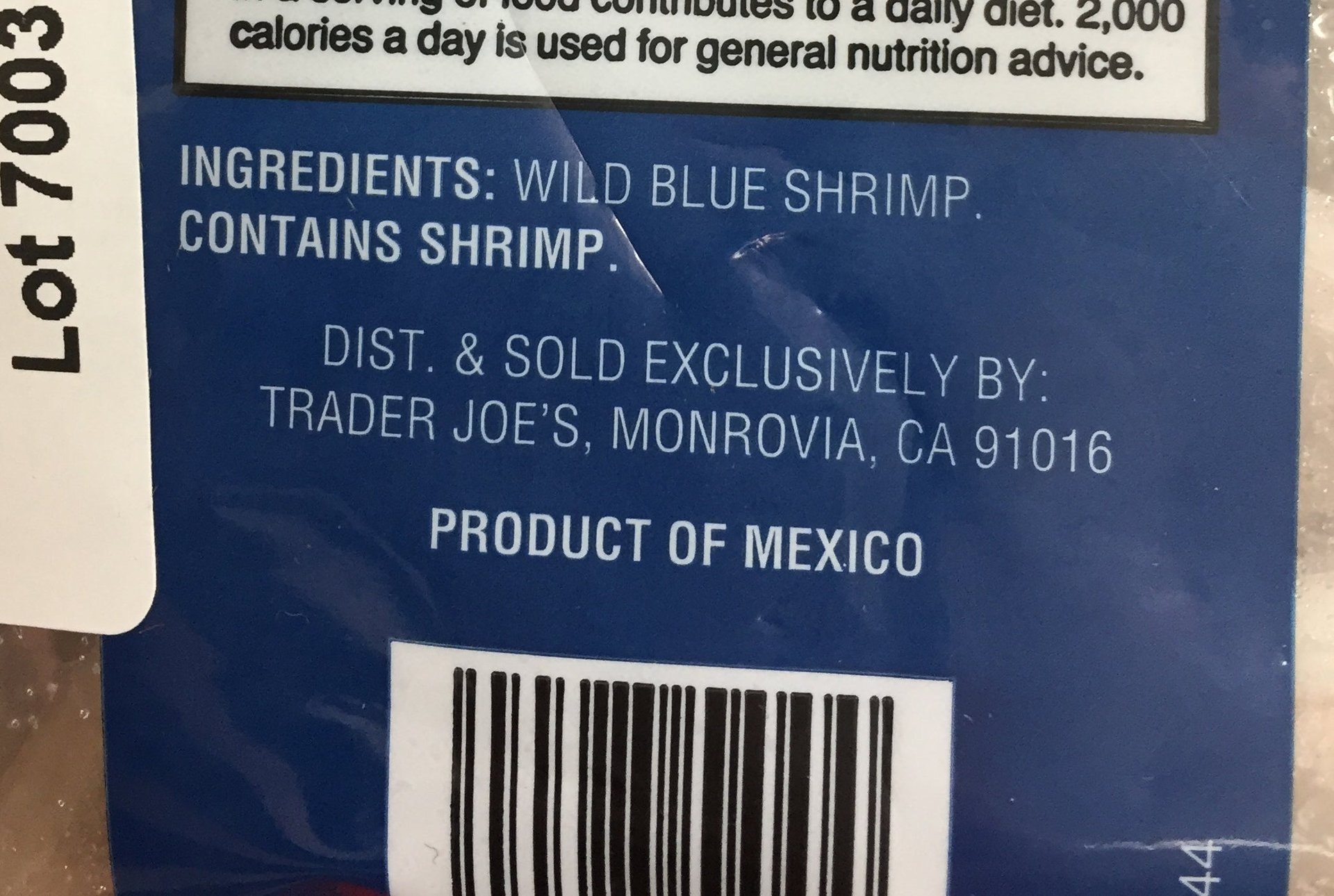

The US is the main buyer of Mexican shrimp, importing about $275 million worth of the seafood in 2016. The conservation coalition hopes that consumers can force Mexico to finally crack down on gill net fishing in the vaquita’s waters. It will be toting a billboard advertising the boycott around Boston next week, targeting businesses participating in one of the seafood industry’s largest annual trade conventions, “Seafood Expo North America”) as well as the local Trader Joe’s, “a known retailer of Mexican shrimp” throughout the country.

Shrimp fishermen aren’t the only ones who use vaquita-killing gill nets in these waters. As Quartz has reported, Chinese demand for totoaba, a rare type of fish also found only in the Gulf of California, has taken a heavy toll in recent years. Totoaba fishing has been outlawed by Mexico, but totoaba bladders still sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars in China—and Mexico hasn’t been vigilant about patrolling its waters to enforce the law.