Five years into an economic depression, Greek stocks have been plunked into the same basket as Peru, Poland, Thailand and Turkey.

MSCI, the firm that oversees the family of global equity market indexes that bear its name, just stripped Greece’s stock market of developed market status, citing shortfalls in “market accessibility.”

Market participants have commented that in‐kind transfer and off‐exchange transaction‐like facilities that were introduced in 2008 by the Greek authorities and the Athens Stock Exchange are so restrictive that they are, in practice, unusable. In addition, the long standing absence of well‐established stock lending as well as short selling practices also make the Greek equity market incompatible with the standards of other developed equity markets.

This is bunk. MSCI says itself that its “reasons” for bumping Greece from the developed markets club aren’t exactly new. The real reason is that the Greece’s economy has been so disrupted and damaged by its debt crisis and currency questions it’s just become untenable to class the country among the world’s more functional economies. What’s more, it’s also difficult to find large, easy-to-trade Greek public companies to include in any kind of Greek index. In fact, the MSCI Greek index itself only consists of two companies, and that was only because MSCI made an exception for Greece back in 2012. Since then one of them, Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling, has fled to Switzerland.

For the record, there really is no good definition of what constitutes an “emerging” or “developed” market. Some say it has to do with GDP levels per capita. Some say it has to do with how easily its currency can be traded. Some say it’s just a matter of where a country appears on the World Bank’s economic rankings.

Greece has long fallen somewhere in between the traditional descriptions. Not too long ago there were strong reasons to consider it an emerging market. Its government bonds were traded on Wall Street emerging markets desks. And when in 1999 JP Morgan launched the EMBI Global—a now a key bond benchmark for emerging market debt—it included Greece.

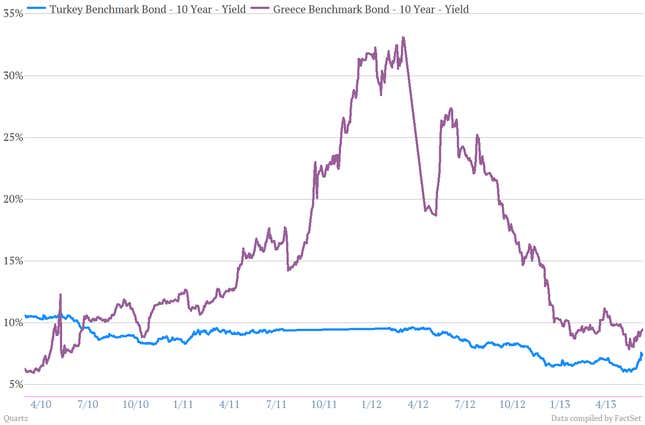

But somehow over the next few years, Greece made the jump into the ranks of developed markets. It adopted the euro in 2001, becoming the twelfth country to do so. Despite—and likely because—Greece was running large deficits, growth was good. The markets decided that Greece was a lot like other of euro countries, such as Germany, and the borrowing costs of the Hellenic Republic collapsed until Greece could borrow almost as cheaply as Europe’s largest economy. Then the debt crisis hit and its borrowing costs exploded. Here’s a how it went down.

So where does Greece figure now? Well, its borrowing costs certainly suggest the market sees it as a riskier proposition, akin to emerging market nations. For example, here’s a look a Greek 10-year yields compared to Turkey 10-year yields over the last couple of years.

And while Greece’s economy is still too wealthy by some measures to be considered a proper emerging market nation, that is changing—fast. Moody’s estimates that Greece’s GDP per capita may fall to $19,500 by 2014, which would be a 36% collapse since 2008. When Greece’s economy gets off this painful roller coaster, it will likely look a lot more like an emerging market nation than its euro zone counterparts.