China is about to make a major change to how it uses a last-resort antibiotic called colistin. As part of its efforts against antibiotic overuse, a global problem that has caused some bacteria to become resistant to drugs, China will entirely stop using the drug in animal feed from the end of this month (April 30). The change, announced late last year (link in Chinese), will also be accompanied by China switching to using the drug for human therapy, according to a paper in the Lancet published in January.

China’s doing the responsible thing, scientists say. And yet the shift could still be very bad for humans.

Colistin, which dates to the 1950s, is an antibiotic with serious side effects, particularly kidney damage, but doctors still turn to it when other options have failed, for example, for sepsis, or for lung and post-surgical infections.

China’s move will see more than 8,000 metric tons of colistin withdrawn from agricultural use. (Although China isn’t the only country to use antibiotics in animal feed, it is by far the largest user, followed by the US.) Antimicrobials are added to animal feed to prevent disease, and promote growth.

The worry is that when colistin is prescribed to humans in China, conditions will be ripe for the spread of colistin-resistant infections in people.

“The rest of the world has not used colistin as a growth promotor. Because of that, you have colistin resistance in the farming sector at a very high level,” says microbiology professor Timothy Walsh at the University of Cardiff, who participated in the Lancet study along with Professor Jianzhong Shen of China Agricultural University.

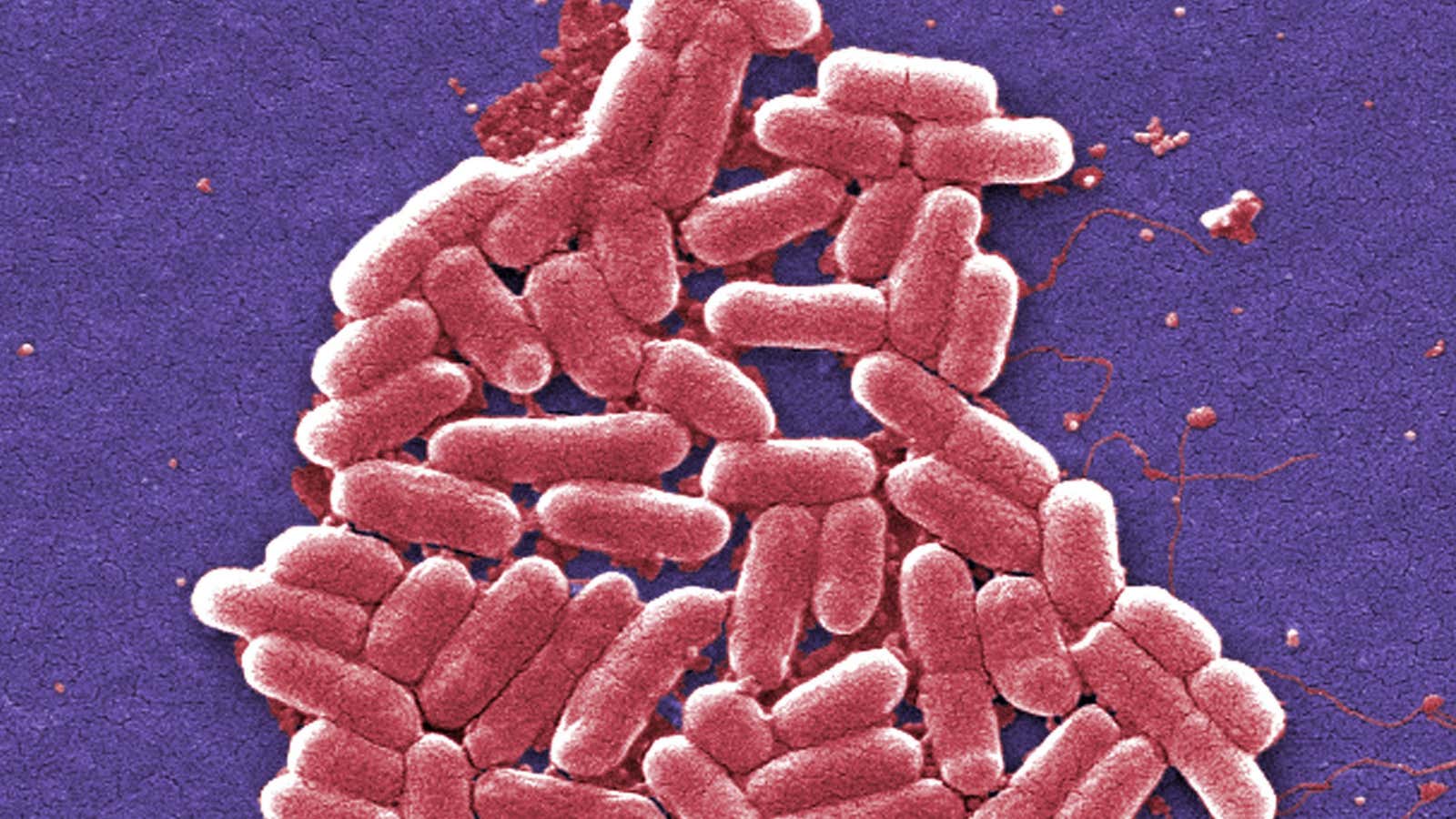

The drug’s decades-long widespread use in agriculture has helped bacteria in animals become resistant to it. Some bacteria have been found to have a colistin-resistant gene known as “mcr-1,” located on a small bit of DNA that can readily transfer from one bacteria to another.

The Lancet paper, funded by scientific institutions in China and the UK, looked at the prevalence of bacteria with the colistin-resistant gene in human infections in two hospitals in China, as well as risk factors for the presence of such bacteria. Research on the mcr-1 gene persuaded the Chinese government to impose the animal-feed ban, although colistin is still approved for treating sick animals, which Walsh also advocates stopping.

The mcr-1 gene was first detected in China in 2015; shortly after that, the gene was also found in bacteria in humans and food in countries like the US and Denmark.

China’s Food and Drug Administration referred Quartz to China’s Health and Family Planning Commission, the top lawmaking state agency for health. The commission hasn’t yet responded to a query about colistin use in humans. Liu Xiaolin, spokeswoman for China’s Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System, an organization founded in 2005 that answers to the health commission, said she did not have information about plans for the drug’s application.

While it’s unclear how China plans to instruct doctors to prescribe colistin, Walsh says it’s likely China will reserve it for the most difficult-to-treat cases, when tests show extensive resistance to other types of antibiotics, particularly the important class of antibiotics called carbapenems.

As other drugs increasingly fail to work, though, doctors in China may find that they have turned more frequently to colistin, like their counterparts in other parts of the world, as the development of new antibiotics has stagnated. ”China has a growing problem in carbapenems resistance, so you are running out of options,” says Walsh.

This could also speed the impending arrival of another form of resistance scientists worry about—bacterial infections that don’t respond either to colistin or to carbapenems.

Biological sciences professor Michael Gillings of Australia’s Macquarie University, who was not involved in the Lancet study, says there are some steps that could help delay the appearance of new superbugs with resistance to both kinds of antibiotics.

The first thing, he says, is to use it judiciously: “Test people beforehand, to see if they have the mcr gene before [doctors] prescribe colistin,” says Gillings.

“The best possible thing is not to use colistin at all,” says Gilling, “But you know, I am not treating a dying patient.”