Johannesburg, South Africa

Zhu Jianying, the owner of a home goods shop in southwest Johannesburg, plans to leave South Africa as soon as she can. Her store is making less than half of what it was two years ago when it first opened. She worries about security—Chinese traders like herself are often targeted. She and her family hardly ever leave the mall that houses her store and their apartment on an upper floor.

“It’s like we’re prisoners in our home,” Zhu says, standing by the cash register in her shop, “Forever Helen,” after the English name she adopted when she moved to South Africa in 2000. Stuffed animals hang from the wall. A digital sign by the entrance says: ”We stock furniture, toys, beds.” On a Sunday afternoon Forever Helen is empty, as are many of the neighboring shops selling electronics, fake flowers, curtains, and furniture brought over from China.

Zhu’s store is in one of South Africa’s many ”China malls,” shopping centers operated by Chinese entrepreneurs and used by Chinese traders across the country. These buildings have become one of the most visible reminders of China’s presence in South Africa, home to the largest Chinese community in Africa.

Africa’s most developed economy has been one of continent’s top destinations for Chinese investment for years. And traders like Zhu make up the bulk of the estimated 350,000 to 500,000 Chinese in South Africa, largely in the big cities of Johannesburg, Pretoria, and Durban.

Now, a relentlessly bad economy, a rising tide of xenophobia, and competition from new malls as well as African traders who have forged their own connections in China, are forcing Chinese traders and business people to consider leaving. The threat of a downgrade of South Africa’s debt, now a reality, and heavy regulations have also dissuaded Chinese businesses and investors from coming in the first place.

The traders who can afford to are returning to China or moving to Western countries like Australia, the United Kingdom, or the United States. Others say they’ll try their luck in nearby African countries. Many, with debts to pay off or without enough money to return home, are stuck where they are.

“What’s the point of working in South Africa where it is more dangerous and lonely when you could be making the same wage in China?” says Mingwei Huang, a doctoral student at the University of Minnesota, echoing sentiments expressed by traders during her research at the China malls.

An estimated half a million to more than 1 million Chinese live in Africa, many of them small-scale traders and entrepreneurs. Chinese traders in African countries from Botswana to Senegal are also struggling to make a profit in the once booming trade of importing cheap goods from China—a sign that the best days of an industry involving thousands of African and Chinese traders, agents, and middlemen across Africa and China might be over.

“Fong Kong”

The Chinese have always occupied an uneasy place in South African society. Some of the earliest Chinese migrants, who came from southern China after the discovery of gold and diamonds in the 1870s and 1880s, were barred from getting mining licenses. Later, Chinese laborers brought to work the gold mines of Witwatersrand in the 1900s were sent back after outcry from white miners.

Even South Africa’s former government, which assiduously classified and segregated its citizens by race, struggled to place the Chinese. Under the apartheid system, the Chinese were lumped together with the country’s Indian population and then with those of mixed race ancestry, in a category called ”coloured.” They were barred from living in certain areas and traveling without approval.

Today, South Africa’s Chinese community, a mix of waves of Chinese migrants from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and almost every province in China, is still not completely welcome. Some South Africans resent the fact that the Chinese are included in black economic empowerment policies established to repair damage done during apartheid. (Only Chinese naturalized or born in South Africa before 1994 are included.)

Locals accuse the Chinese traders of causing the decline of South Africa’s own textile industry. The electronics and other items sold at the China malls are known among South Africans as “fong kong,” a term synonymous with fake or poor quality. Critics of the government’s ties with China call president Jacob Zuma “Fong Kong Zuma.”

Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, the country has seen a new wave of Chinese migration from poorer Chinese towns and counties left behind by their country’s economic rise. They’ve come to work in the malls or in hopes of starting their own businesses selling Chinese-made goods.

Older generations of Chinese migrants criticize them as uneducated peasants. Many of them speak little English and keep to themselves, associating mainly with other Chinese from their same province or hometown.

These Chinese migrants have filled a niche in the country. As South Africa emerged from international isolation following the country’s first democratic elections in 1994, they were there to sell to the emerging middle and lower classes. The rand was strong, making goods sourced in China cheap. At the time, there were few other retailers.

“When we first came, people didn’t even have shoes. There was nothing to buy. Chinese people could sell them so much,” says Qian, a shopkeeper from Zhejiang province at another mall, China City, who moved to South Africa in 1995.

As South Africa’s middle class expanded and the country, helped by commodity exports, became one of the world’s biggest emerging markets, the China malls multiplied. By 2011, there were at least 18 Chinese-run shopping centers across Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town, in border cities like Musina between South Africa and Zimbabwe, and in some of the country’s less developed urban townships.

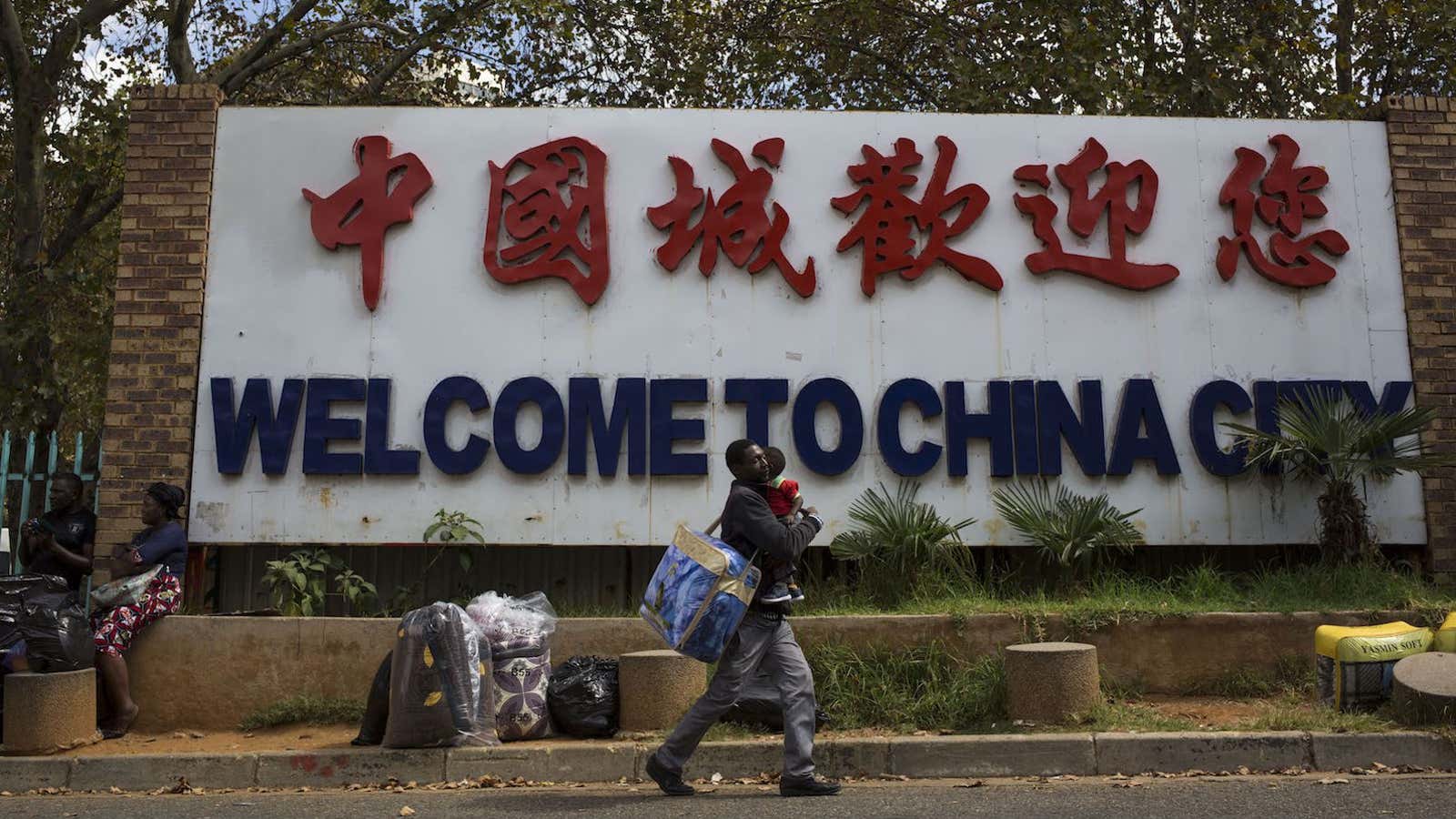

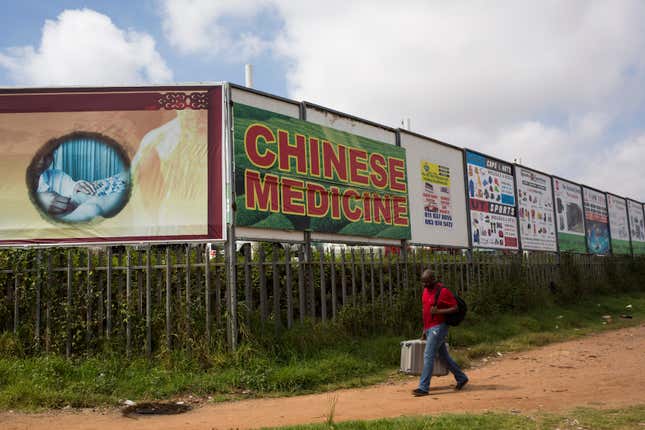

The malls are hard to miss: the large fenced-in complexes are manned by security guards with guns and flanked by billboards advertising their latest deals. Driving along Main Reef road along the old mining belt, between the township of Soweto and inner city Johannesburg, one can stop at any number of China malls: “China Cash and Carry” “China Multiplex,” “Dragon City,” and more.

In a way, the China malls and the people who work in them are a kind of proxy for China and its growing role in South Africa. For almost a decade, China has been South Africa’s largest trading partner and an ally of the ruling African National Congress (ANC), inviting the country to join the BRIC economic bloc in 2011. The ANC has sent several delegations to study China’s economic model and recently said the Chinese Communist Party should be a “guiding lodestar of our own struggle.” There are more than 300 Chinese businesses in South Africa, in finance, mining, telecom, automobile, and logistics.

For most South Africans, “what ‘China’ represents is still pretty abstract and behind doors when it comes to large-scale investment and diplomacy,” says Huang, the doctoral candidate at the University of Minnesota. “These malls are the everyday face of Chinese investment and capital to South Africa. They are small traders, but they are stand-ins for larger geopolitical forces.”

“Not just for white people”

China City is a darkly lit warren of wholesale stalls in central Johannesburg. Signs direct customers to stores selling sneakers, luggage, wigs, and furniture. Music blares from a nearby stall as people sell popcorn and ice cream at the entrance. The center, the first China mall to open in 1995 when a Hong Kong businessman converted an old supermarket into storage and retail space, has been manned almost entirely by Chinese shop owners for years.

“It used to be that there were more [Chinese] people coming than leaving. Now it’s the opposite,” says Qian, the shopkeeper from Zhejiang province. She sits behind a display counter of watches at her store, identified by a half torn sign with her shop number, that she’s operated for most of the last two decades.

Now, almost as many African traders as Chinese are running stores at the mall. More Africans have forged connections in China and can go directly there to source their goods. Others haven’t been as affected as the Chinese have been by the weakening rand since they buy their goods in South Africa.

“It’s better because then the business is not just for one country, not just for white people,” says Mathew Thyah, 26, from Malawi who manages a sneaker shop owned by a Senegalese entrepreneur. He’s referring to the Chinese as white.

Thyah may get his wish. China malls across the city are increasingly deserted. At China Mart, a fortress-like shopping complex also in the Crown Mines industrial area, several stores sit empty. Qin Hans and his wife, who arrived in South Africa almost 30 years ago from Nanjing, sell clothing from traditional African wear to golf t-shirts.

On a recent Friday afternoon, they had just one customer who spent 600 rand (about $45). In the past they would expect at least 15 customers a day. The owners of a store across the hall selling panty hose and lingerie didn’t even bother coming in. Another neighbor has left his store shut for the last two months. Switching to English from Mandarin, Qin says, “Not sustainable.”

Most Chinese traders say the rand, one of the world’s worst performing currencies last year, has been their biggest obstacle. Last year, it reached a record low and is tumbling again as protesters call for Zuma to step down and the country’s economic outlook stays bleak.

Jeremy Zhao, who runs a party decoration store in China City, says the rand is hurting his business, which depends on people’s willingness to splurge. “There are too many Chinese malls. That and the rand isn’t so strong so people have less money to spend on parties.”

In the face of inflation, low wage growth, and a prevailing sense of job insecurity, people are feeling squeezed. A McKinsey survey last year of about 1,000 South Africans found that 70% were afraid of losing their jobs and half were living paycheck to paycheck.

In some ways, the China malls that once filled the void of affordable consumer goods aren’t as needed anymore. With 2,000 shopping centers, many of which have been built in the last 10 years for its population of 53 million, both middle and lower class South Africans have more options. South Africa is now seventh in the world in terms of space devoted to shopping centers.

It’s not just the Chinese in South Africa who are struggling. In Senegal and Ghana, the Chinese find themselves competing in markets already saturated with Chinese goods. Chinese in Botswana are facing competition from local traders and a weakening local currency, according to researchers.

The number of Chinese in Angola has fallen to about a quarter of what it was four years ago, according to the Angola-China Industrial and Commerce Association. African traders based in China or on the continent importing Chinese goods are also seeing business slow.

As importing from China has become easier, competition has gotten worse. It’s now much easier for a trader in Nairobi to go to Guangzhou, buy goods and ship them back. More Africans traders have brokers in China with whom they can place their orders over WhatsApp or email, eliminating the need for Chinese middlemen on the ground in Africa.

“Knowledge of China and how to get there has increased dramatically,” says Emma Lochery, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Liege in Belgium who has researched trade between Eastleigh and Guangzhou.

“It starts with words”

Life in South Africa is hard in other ways for the Chinese. Competition is fierce among traders and the Chinese community is far from unified. There are more than 100 different Chinese associations just in Johannesburg and various factions based on when and from where one moved to South Africa.

The Chinese haven’t been attacked the way African migrants from elsewhere on the continent have. But they’re often the target of robberies and hijackings, and growing anti-Chinese sentiment is a concern. As the South African economy has worsened, hostility towards the Chinese along with other foreigners has increased, according to Erwin Pon, head of the Chinese Association of Gauteng.

The association has filed hate speech lawsuits as well as a complaint with South Africa’s Human Rights Commission over comments left on their Facebook page last month. After the association organized a Chinese New Year celebration, advertised on its page, users left remarks calling for the Chinese to be banned, “wiped out,” or for their children to be killed. “Can we not stop these slant eyed freaks from coming into the country?!” one comment said.

“It always starts with words. Once those words become more angry, anger turns into violence,” Pon says.

The trading economy

The departure of Chinese traders doesn’t bode well for the thousands of traders, hawkers, and owners of small shops in South Africa and across southern Africa. Less than a few kilometers from China City is Park Station, a hub of trains and buses where traders transiting from Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia and other nearby countries come into the city to buy goods.

They can walk over the China City, make their purchases, head back to the bus station and go straight home to sell them. In South Africa, hawkers that sell goods in traffic, Ethiopian traders downtown, and South Asian shopkeepers all buy their goods from the Chinese.

Satiad Hussain sells gauzy fabric and rhinestone-studded chairs for weddings at China Mall, which also houses Zhu’s home goods shop. He buys all his materials from the Chinese and takes their departure as a sign things aren’t likely to improve. ”It’s really bad if the Chinese are going,” he says.

These networks are important. In sub-Saharan Africa, the size of the informal economy as a percentage of gross domestic product is 41% on average, according to the International Labour Organisation. In South Africa that figure is around 30%, but the informal economy is even more important here given high rates of unemployment.

Right now, South Africa’s Chinese community is “providing a particular service or function that is important to people involved in that business within trading communities,” says Romain Dittgen, an urban studies researcher at Wits University in Johannesburg.

The overall Chinese community is feeling the effects of South Africa’s slowdown and increasing hostility to foreigners. Chinese residents whose families have been in South Africa for generations have also decided to move on. Pon, who was born in South Africa, says that as much as half of younger Chinese residents, those between the ages of 30 and 50, have left for the United States, the United Kingdom, or mega-cities in China where they believe they’ll have more business opportunities.

Pon, also head of the China division at Rand Merchant Bank, part of one of the five largest banking groups in the country, says Chinese companies have become less interested in South Africa over the last four years. Chinese investment in the country, after peaking before the financial crisis, is still growing but more slowly now.

Officials at the Chinese Embassy in Pretoria say the number of Chinese in South Africa has always fluctuated, but Chinese businesses are still committed to the country. “The Chinese are everywhere in South Africa—from Chinatown in Johannesburg, to factories, mines, restaurants, and shops. These people have taken root and are working hard in South Africa,” the embassy wrote in an email to Quartz.

The embassy blamed current struggles of the Chinese community on the slow recovery of the global economy after the financial crisis. “South Africa’s economy is also sliding, which affects Chinese people’s investment and businesses in South Africa.”

You can’t go home again

Not all the Chinese who’d like to go home can. Many can’t afford the costs of going back to China and starting over. Others find that after years of being away they’ve lost the contacts or guanxi they need for doing business or finding work. Some are too enmeshed here, with children in school, property to pay off, and goods left to sell.

Wei Zhihong, who runs a shop in Johannesburg’s China City selling hats and belts says he can’t afford to live in China where living costs have risen and inequality is among the highest in the world. “Business is bad but the opportunity is still better here than at home.”

Many feel like they have more opportunity in African countries, even those whose economies are a fraction of the size of China’s. Wang, a man from Guangdong province sells electronics at China Mall, down the hall from Zhu. Even though his business is struggling, he won’t go back to China. “Comparing South Africa with China, there are good and bad sides. For poor people,” he says, like him, “South Africa is better.”

Additional reporting by Echo Huang and Zizhu Zhang.