Facebook, the world’s largest communication platform, doesn’t appear to understand what “conversation” means.

The tech giant strives to ”connect the world” and enable people to “share what matters to them.” And, with the platform expecting to reach 2 billion monthly active users by mid-2017, it’s undeniably successful. (Even if plenty of what’s shared includes fake news, an issue Facebook plans to remedy with new ”social infrastructure.”)

Yet there’s a fundamental difference between sharing (posting) and actual conversation—one that Facebook is intent on muddling with new features that turn all comments into pop-up messages.

Conversation demands time, attention, and sustained interest. To a company whose revenue is dictated by the time users spend on its site, these values translate to cash, cash, and more cash.

Through Messenger, Facebook has used the basic human need for direct communication to increase usage of their service. Now they’ve gone a step further, testing new comment-turned-message features on an undisclosed number of users.

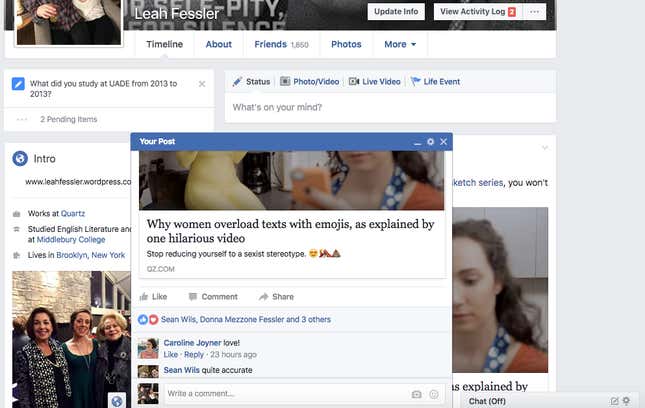

The first new feature affects desktop users only, automatically turning comments into pop-up tabs when your News Feed is open.

The second new feature also automatically turns post comments to messages, but re-formats them as text bubbles, making the thread look nearly identical to a personal message on the Facebook Messenger app. This feature was first spotted by The Next Web’s Matt Navarra:

Here’s another version of the comment bubbles:

When asked to explain these features, Facebook said: “We are always working to make Facebook a more visual and engaging place to have conversations. So we’re testing multiple design updates in News Feed, including a more conversational way to comment on posts.”

Comment threads are often ”bulletin boards of zingers” and plagued by trolls, says technology ethicist David Ryan Polgar. This makes them often inhospitable to meaningful dialogue. Thus Facebook’s drive to make comments more dynamic is neither surprising nor illogical.

Yet these new features reveal how, by trying to make digital dialogue more like “real” conversation, we often overlook the unique properties that constitute conversation, says Sherry Turkle, author of the New York Times Bestseller Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in the Digital Age.

Comments are not conversation, Turkle explains, because people use comments to add information—to digress and insert thoughts on the topics being discussed. ”This means that comments don’t have the empathic reactivity of conversation, and why it seems somehow odd to see them in ‘bubbles’ as though they were conversational elements,” she says.

By turning comments into bubbles that appear like messages, people will likely begin making shorter, more immediately reactive comments like the kind we make when conversing in person—comments like “totally,” or “really?”

“But if this happens, they may lose something really valuable they had as comments,” says Turkle, ”They had their own integrity. They gave their own kind of space.” Ironically for Facebook, this space is what actually inspires conversation. Conversation requires agency and intention from both or many parties; it’s sparked when two people are interested in the same stimuli, and actively decide to discuss it. Comments can provide that, motivating people to reach out and converse with one another. By forcing these comments into a pop-up message instead, Facebook effectively takes conversational agency for us, which is off-putting at best.

More, conversation fosters closeness, a reality this feature also overlooks by implying that all commenters are deserving of conversational intimacy. Whether the visual of a pop-up message actually changes the privacy of the comment thread is somewhat irrelevant, says ethicist Polgar, because the visual appears to cross the line between intimate messaging and public comments. That’s enough to trigger many users’ discomfort.

More often than not, the dialogue we have on Facebook isn’t with other users, it’s with ourselves. Inherently self-presentational, Facebook allows us to curate our image, intellect, social circles, and frankly, our lives. Thus, if our aversion to these forced comment messages spurs any question, it’s this: We want to share, but do we really want to talk?

Until Facebook realizes the answer, its ”conversational” features may continue to fall flat.