“A computer lets you make more mistakes faster than any other invention with the possible exceptions of handguns and Tequila.” — Mitch Ratcliffe

Soon every mistake you’ve ever made online will not only be available to your internet service provider (ISP) — it will be available to any corporation or foreign government who wants to see those mistakes.

Thanks to last week’s US Senate decision and yesterday’s House decision, ISPs can sell your entire web browsing history to literally anyone without your permission. The only rules that prevented this are all being repealed, and won’t be reinstated any time soon (it would take an act of Congress).

You might be wondering: Who benefits from repealing these rules? Other than those four monopoly ISPs that control America’s “last mile” of internet cables and cell towers?

No one. No one else benefits in any way. Our privacy (and our nation’s security) have been diminished so a few mega-corporations can make a little extra cash.

In other words, these politicians — who have received millions of dollars in campaign contributions from the ISPs for decades — have sold us out.

How did this happen?

The Congressional Review Act (CRA) was passed in 1996 to allow Congress to overrule regulations created by government agencies.

Prior to 2017, congress had only successfully used the CRA once. But since the new administration took over in January, it’s been successfully used 3 times — for things like overturning pesky environmental regulations.

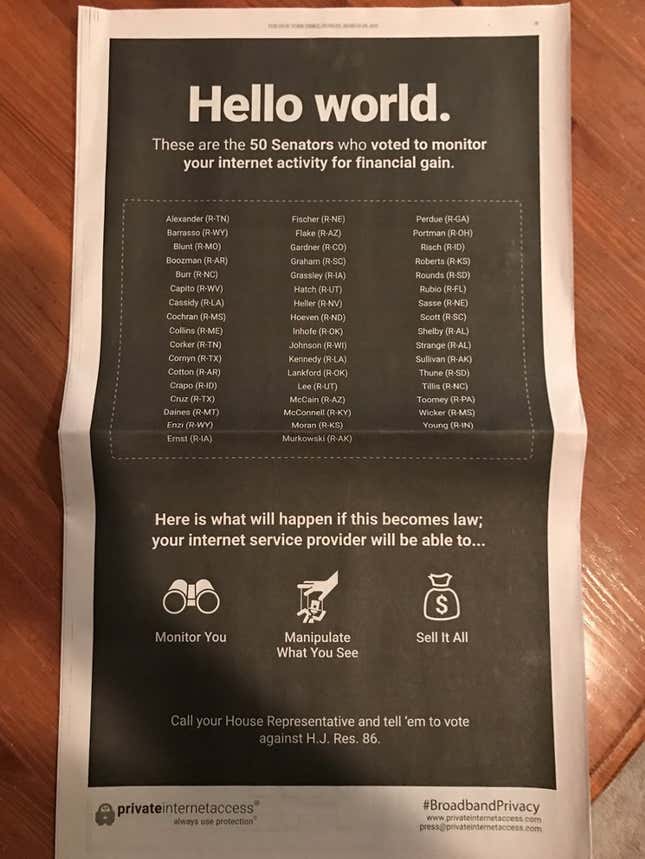

Senator Jeff Flake — a Republican representing Arizona — lead the effort to overturn the FCC’s privacy rules. He was already the most unpopular senator in the US. Now he may become the most unpopular senator in US history.

Instead of just blaming Flake, though, let’s remember that every single senator who voted in favor of overturning these privacy rules was a Republican. Every single Democrat and Independent senator voted against this CRA resolution. The final vote was 50–48, with two Republicans voting against the resolution, and another two choosing not to vote.

“Relying on the government to protect your privacy is like asking a peeping tom to install your window blinds.” — John Perry Barlow

The CRA resolution passed yesterday in the House of Representatives, where 231 Republicans voted in favor of removing privacy protections against 189 Democrats who voted against it. (Again, not a single non-Republican voted to remove these privacy protections.)

All that’s left is for the Republican president to sign the resolution, which he most certainly will do.

So what kind of messed-up things can ISPs now legally do with our data?

According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, there are at least five creepy things the FCC regulations would have made illegal. But thanks to the Senate, ISPs can now continue doing these things as much as they want, and it will probably be years before we can do anything to stop them.

- Sell your browsing history to basically any corporation or government that wants to buy it

- Hijack your searches and share them with third parties

- Monitor all your traffic by injecting their own malware-filled ads into the websites you visit

- Stuff undetectable, un-deletable tracking cookies into all of your non-encrypted traffic

- Pre-install software on phones that will monitor all traffic — even HTTPS traffic — before it gets encrypted. AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile have already done this with some Android phones.

So how do we have any hope of protecting our privacy now?

According to a study by the Pew Research Center, 91% of adults agree or strongly agree that “consumers have lost control of how personal information is collected and used by companies.”

But we shouldn’t despair. But as the same British Prime Minister who cautioned us to “hope for the best and prepare for the worst” also said:

“Despair is the conclusion of fools.” — Benjamin Disraeli in 1883

Well we are not fools. We’re going to take the actions necessary to secure our family’s privacy against the acts of reckless monopolies and their political puppets.

And we’re going to do this using the most effective tools for securing online communication: encryption and VPNs.

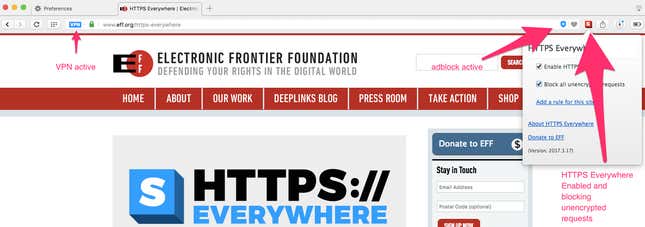

Step 1: enable HTTPS Everywhere

As I mentioned, ISPs can work around HTTPS if they are able to factory-install spyware on your phone’s operating system. As long as you can avoid buying those models of phones, HTTPS will give you a huge amount of additional protection.

HTTPS works by encrypting traffic between destination websites and your device by using the secure TLS protocol.

The problem is that, as of 2017, only about 10% of websites have enabled HTTPS, and even many of those websites haven’t properly configured their systems to disallow insecure non-HTTPS traffic (even though it’s free and easy to do using LetsEncrypt).

This is where the EFF’s HTTPS Everywhere extension comes in handy. It will make these websites default to HTTPS, and will alert you if you try and access a site that isn’t HTTPS. It’s free and you can install it here.

One thing we know for sure — thanks to the recent WikiLeaks release of the CIA’s hacking arsenal — is that encryption still works. As long as you’re using secure forms of encryption that haven’t yet been cracked — and as far as we know, HTTPS’s TLS encryption hasn’t been — your data will remain private.

“The average busy professional in this country wakes up in the morning, goes to work, comes home, takes care of personal and family obligations, and then goes to sleep, unaware that he or she likely committed several federal crimes that day.” — Harvey Silverglate

By the way, if you haven’t already, I strongly recommend you read my article on how to encrypt your entire life in less than an hour.

But even with HTTPS enabled, ISPs will still know — thanks to their role in actually connecting you to websites themselves — what websites you’re visiting, even if they don’t know what you’re doing there.

And just knowing where you’re going — the “metadata” of your web activity — gives ISPs a lot of information they can sell.

For example, someone visiting Cars.com may be in the market for a new car, and someone visiting BabyCenter.com may be pregnant.

That’s where using a VPN comes in.

How VPNs can protect you

VPN stands for Virtual Private Network.

- Virtual because you’re not creating a new physical connecting with your destination — your data is just traveling through existing wires between you and your destination.

- Private because it encrypts your activity before sending it, then decrypts it at the destination.

People have traditionally used VPNs as a way to get around websites that are blocked in their country (for example, Medium is blocked in Malaysia) or to watch movies that aren’t available in certain countries. But VPNs are extremely useful for privacy, too.

There are several types of VPN options, with varying degrees of convenience and security.

Experts estimate that as many as 90% of VPNs are “hopelessly insecure” and this changes from time to time. So even if you use the tools I recommend here, I recommend you take the time to do your homework.

Browser-based VPNs

Most VPNs are services that cost money. But the first VPN option I’m going to tell you about is convenient and completely free.

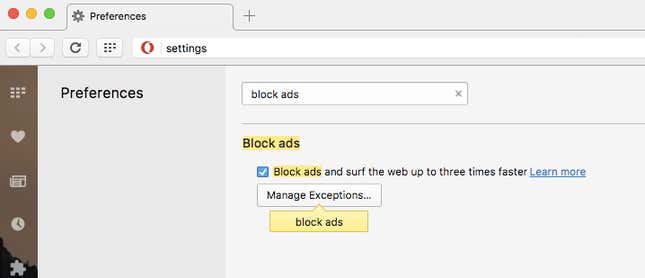

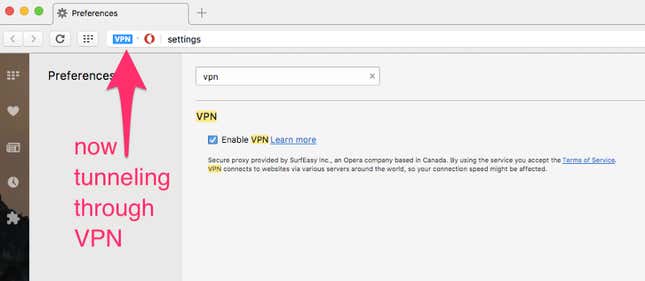

Opera is a popular web browser that comes with some excellent privacy features, like a free built-in VPN and a free ad blocker (and as you may know, ads can spy on you).

If you just want a secure way to browse the web without ISPs being able to easily snoop on you and sell your data, Opera is a great start. Let’s install and configure it real quick. This takes less than 5 minutes.

Before you get started, note that this will only anonymize the things you do within the Opera browser. Also, I’m obligated to point out that even though Opera’s parent company is European, it was recently purchased by a consortium of Chinese tech companies, and there is a non-zero risk that it could be compromised by the Chinese government.

Having said that, here’s how to browse securely with Opera:

Step #1: Download the Opera browser

Step #2: Turn on its ad blocker

Step #3: Turn on its VPN

Step #4: Install HTTPS Everywhere

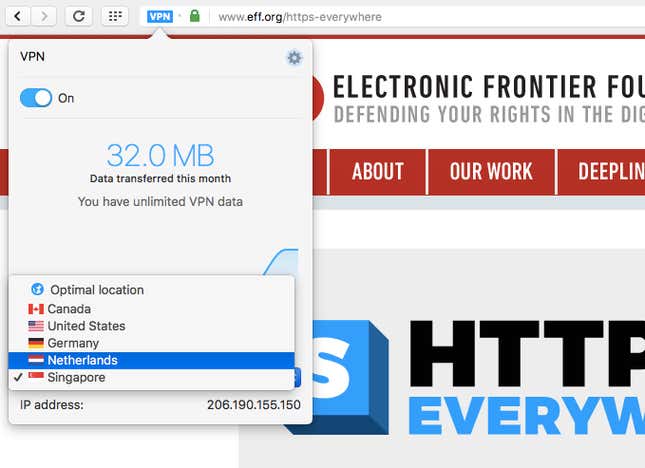

When you’re done, Opera should look like this:

Presto — you can now browse the web with reasonable confidence that your ISPs — or really anyone else —don’t know who you are or what you’re doing.

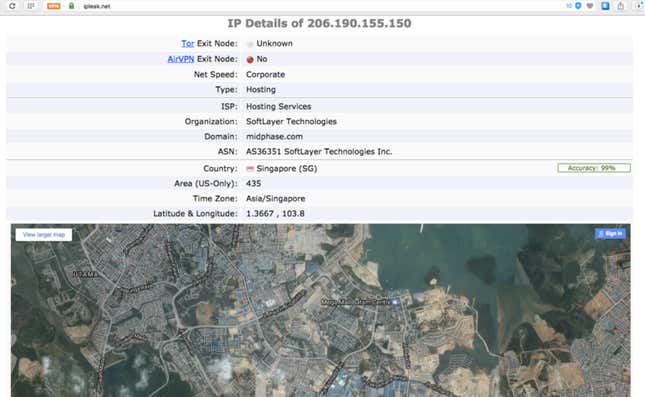

You can even set your VPN to a different country. Here, I’ve set mine to Singapore so websites will think I’m in Singapore. To test this out, I visited ipleak.net and they did indeed think I was in Singapore.

Since the internet is complex, and data passes through hundreds of providers through a system of peering and trading traffic, US-based ISPs shouldn’t be able to monitor my traffic when it emerges from Singapore.

If you want to take things next level, you can try Tor, which is extremely private, and extremely hard to de-anonymize (though it can be done, as depicted in the TV show Mr. Robot — though it would require incredible resources).

Tor’s a bit more work to set up and use, and is slower than using a VPN. If you want to learn more, I have a getting-started guide for Tor here.

VPN Services

The most common way people get VPNs is through a monthly service. There are a ton of these. Ultimately, you must trust the company running the VPN, because there’s no way to know what they’re doing with your data.

As I said, some VPNs are improperly configured, and may leak personally identifying data.

Before you buy a VPN, read up on how it compares to other here. Once you buy a VPN, the best way to double check that it’s working properly is to visit ipleak.net while using the VPN.

Even though most users of VPNs are companies with remote employees, the NSA will still put you on a list if you purchased a VPN. So I recommend using something anonymous to do so, like a pre-loaded Visa card. (By the way, Bitcoin is not anonymous.)

There are dozens of VPN services, and there’s no clear “winner.” I asked people on Twitter which VPNs they were using and got a variety of answers:

Some routers are designed to work with VPNs at higher speeds than others. If you want to use a VPN at the router level, and your internet connection is less than 100 mps, this router will probably suffice. Otherwise, you’ll need to pay a bit more for a router like this one.

If you don’t trust the router companies, you can modify a router using Tomato USB. It’s an alternative open source Linux-based router firmware that’s compatible with some off-the-shelf routers.

Privacy is hard. But it’s worth it.

Privacy is a fundamental human right, and has been declared so by the United Nations.

Still, many people believe we live in a “post-privacy” era. For example, Mark Zuckerberg claims privacy isn’t that important any more. But look at his actions. He paid $30 million to buy the 4 houses adjacent to his Palo Alto home so he could have more privacy.

Other people are just too jaded and shell-shocked by all the data breaches around us to believe that privacy is still worth the fight.

But most people who say they don’t care about their own privacy anymore just haven’t really given it much thought.

“Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.” — Edward Snowden

Last week’s US Senate vote is just the latest in a series of events that show how we can’t trust governments to act in the interest of consumers when it comes to their privacy.

We need stronger privacy protections enshrined in the law.

In the meantime, we’ll just have to look out for ourselves, and educate other people to do the same.

This post originally appeared on Medium. Follow Quincy on Twitter @Ossia. Learn how to write for Quartz Ideas. We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.