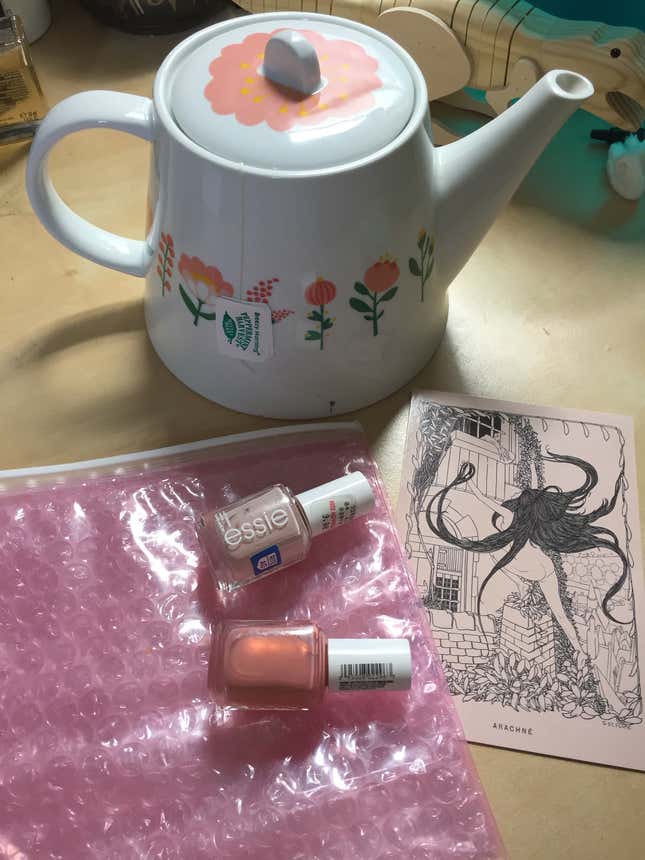

Last weekend, I was out and about in New York City. I picked up two bottles of nail polish, a cheap teapot from Flying Tiger, and a postcard from the Morgan Library, where I’d gone to see some Emily Dickinson manuscripts. It was only when I got home that I recognized a common theme. Although all of my purchases were theoretically different colors, every single one could reasonably called “millennial pink.”

The rise of “millennial pink” has been extensively chronicled. It is theoretically a pale pink with a neutral shade mixed in—either a pale grey-pink, like Pantone’s “Rose Quartz” (their color of the year for 2016, which may have kicked off the whole trend) or a browner pinkish-peach, which Pantone is calling “Pale Dogwood.” In practice, however, millennial pink is whatever shade of pink you want it to be. As Heather Schwedel noted at Slate, the term has come to cover nearly every iteration of the color, from traditional baby-nursery and bubblegum pastels (The Grand Budapest Hotel color scheme, Le Creuset cookware in “hibiscus”) to dusky salmon shades that are barely pink at all (Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter, pamplemousse-flavored La Croix cans). Ivanka Trump’s Republican National Convention dress is millennial pink; so is Drake’s sweater. It’s the color of choice for both cool-girl makeup brand Glossier and beleaguered period-underwear brand Thinx. Bite Beauty is selling a “millennial pink” makeup kit of three different colors, one of which appears to be glittery, iridescent orange. At this point, it’s harder to determine what is not millennial pink than what is.

I don’t question the color’s appeal. Pink is approachable; it’s wearable; it’s appropriate for springtime. What I object to is not the prominence of millennial pink—that is, pink—but our endless intellectualizing about the forces behind this phenomenon. In attempting to rationalize our attraction to the color, the media is revealing just how uncomfortable a lot of people are with liking something that’s associated with femininity.

Nearly every article written on millennial pink takes care to stress its gender-neutral qualities, and to dissociate it from the bad-taste, too-girly “Barbie” pinks of ages past. (Although I would defy you to look at certain examples, like the Pepto-Bismol pink interior of New York’s Pietro Nolita (complete with heart-shaped bathroom mirror!) without being mentally transported to a Malibu Dream House.) In fact, the idea that the shade isn’t girly seems to be the whole point of its appeal. “With Millennial Pink, gone is the girly-girl baggage; now it’s androgynous,” New York Magazine declares, quoting fashion editor Amy Larocca as saying that “[pink is] fundamentally a great color that had been gendered to the point where it became obsolete.” In The Ringer, Leatrice Eiseman of Pantone explains that, “With female consumers, pink is sometimes also seen as a little girl color… [the] Dogwood shade has a little bit of sophistication attached to it.”

Esquire, wrestling manfully with the existence of pink sneakers and shorts for men, notes that “the crossover of these traditionally feminine tones perhaps shows we’re at a post-gender point with color,” ultimately going full Masters’ thesis to declare pink “an emblem of an age both ostensibly post-gender and, at the same time, obsessed with gender politics, a palette of ‘wokeness’ and a soft-hued sign of the times.”

Yes, surely, this trend must be a sign of this gender-free, millennially woke new age. Unless, that is, you’ve ever seen an episode of Miami Vice, in which case you’ve surely spotted Don Johnson and Philip Michael Thomas, guns a-blazing, relentlessly murdering drug lords while wearing pastel t-shirts and fetching salmon suit jackets. Ultimately, pink’s gender associations less immutable than we suppose. “Pink for girls and blue for boys” was codified at some point in the 1940s, but it didn’t really take off until the mid-1980s, when prenatal gender testing became common enough that parents could buy gendered nursery furniture in advance.

Without that lingering gender panic, there is nothing particularly unusual about millennial pink. Every era has its own color fetishes, and they are often far more inexplicable. The “avocado” and “mustard” shades of the 1970s, once thought to signal a tasteful earthiness, lived on for decades in high-school lockers and dishwashers that looked as if they had been ritualistically coated in baby crap. In 1988, the New York Times ran a feature on the mainstreaming of chartreuse, though they noted that the intense, radioactive-bile green was so divisive that designers had to call it something other than “chartreuse” to sell it. (“Nobody looks good in it. Because of the high condensation of green and yellow, it is lethal, I repeat, lethal. The teeth look yellow. This is just a deadly thing,” said makeup artist Pablo Manzoni.) In the late 2000s, I recall being swept up in a fad for pairing baby-blue with dark brown.

By contrast, pink is actually a fairly classic, traditional shade. It’s not always fashionable, but it also never goes out of style. It really was ubiquitous throughout the 1980s; one millennial-ish pastel shade was used in seemingly every sweater sold by JC Penney between 1979 and 1990. In the 2000s, pastel and fuchsia pinks were the go-to signifier of young women (as in Mean Girls) and glittery baby pink was indelibly associated with a particular, Paris-Hilton-ish brand of high-gloss femme. Pink Juicy Couture track suits, pink rhinestone flip phones, and sparkly pink lip gloss were everywhere. The only decade in my lifetime that I can recall as not being notably pink was the 1990s—and that’s only if you discount the extremely pink Clueless, the sometimes-pink pastel nail polish trend, or the “edgy,” acidic Day-Glo pink that decorated most of the “cool” products aimed at tweens throughout the first part of the decade.

There are plenty of reasons for pink’s longevity, but the most obvious, and least think-piece-friendly reason, is just that pink, well, looks nice. It comes in a wide variety of shades, so it flatters pretty much any skin tone. Unlike mustard, or chartreuse, or any other color-of-the-moment, there’s really no one who looks terrible in some variation of pink. In fact, most people look better: Women who want to look younger have been stocking their apartments with pink lightbulbs for ages. If, like me, your skin reads as “jaundiced” or “corpse” throughout the winter months, wearing pink is a quick cheat to looking healthier, or at least less like a murder victim who’s been recently drained of blood and propped up at a computer desk. You can wear it to the office, or wear it out, without looking out of place. Stripped of its gender baggage, pink is basically just another neutral; a color, like gray or brown, that is universally wearable, inoffensive, and requires very little thought to pull off.

Yet we keep obsessing over millennial pink, including, yes, this piece right now. The response seems to betray our culture’s fundamental assumption that what is feminine is always, somehow, suspect—the same logic that leads us to condescension about “chick flicks” and women’s magazines. The underlying idea here is that “women’s tastes” are not quite “taste,” and that for girls’ interests or preferences to have any real legitimacy, they need to be somehow de-feminized.

But just as femininity should not be mandatory for any woman, it shouldn’t be treated as an automatic negative either. So friends, let’s admit it: Millennial pink is simply pink. You like it, and, thanks to marketing, so do a lot of little girls. But people always have liked pink; people probably always will like pink; if you like pink, whoever you are, it is not remotely a big deal. Just go ahead and embrace it, without worrying that it makes you tacky, or basic, or girly, or shallow. Pink is a pretty color. And the sooner we all stop making a fuss over it, the sooner that “post-gender” era can actually begin.