Asia’s richest man, Li Ka-shing, is pouring money into burning trash. The real estate tycoon is leading a consortium to buy Dutch waste treatment company called AVR for $1.26 billion (pdf) from private equity groups Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and CVC Capital Partners. AVR is the biggest “waste-to-energy” company in the Netherlands, which burns trash to generate thermal electricity.

In January, Li’s Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings (CKI) made a similar investment in New Zealand when it snapped up diversified waste management company EnviroWaste for $501 million. (In addition to waste-to-energy, EnviroWaste also manages landfills.) At the time, Kam Hing Lam, CKI’s managing director, praised the waste management industry as a solid source of growth because the ”rate of increase in waste is fundamentally linked to growth in population, GDP and consumption.”

It seems like a safe bet. Waste produced by city-dwellers has almost doubled in just 10 years. By 2025, the 1.3 billion tons of trash generated each year will grow to 2.2 billion tons annually, according to a recent report by Daniel Hoornweg and Perinaz Bhada-Tata (pdf).

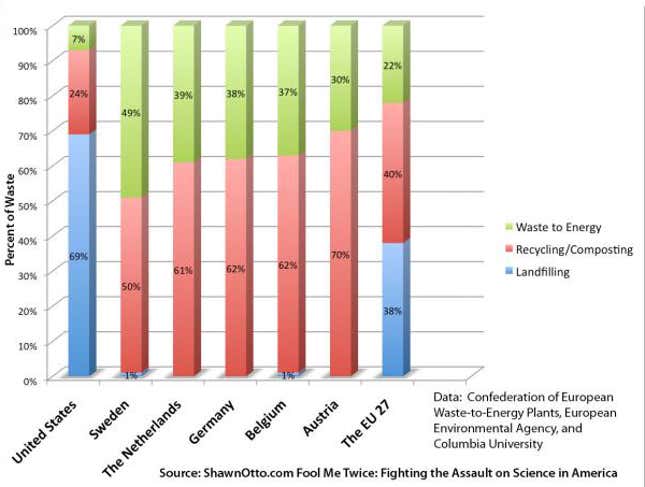

Along with several other European countries, the Netherlands is at the forefront of the waste-to-energy business. Here’s how it compares with the US:

The waste-to-energy business is sure to grow. The European Union has set stringent targets for use of renewable energy by 2020. That also means trash reduction, which is why some cities leading the waste-to-energy charge have been importing trash to meet their thermal energy needs.

Many Northern European countries have so reduced their trash production that waste-to-energy plants need to import from other areas. Oslo residents produce so little usable trash that the city now imports garbage to fuel its thermal energy plants. The same goes for Sweden.

Often trash importers are willing to pay for outside waste. As we’ve discussed in the past, the US doesn’t recycle very much of its trash; instead it sends it to China and other countries to do the recycling, which boosts its exports. China uses disposed plastic resin to produce its own plastics.

In other cases, trash producers have to pay to dispose of their waste. For instance, Naples, Italy, which produces more trash per square meter than anywhere globally, sends hundreds of thousands of tons of trash to Germany and the Netherlands, including to AVR. The city’s trash crisis is so severe that it has paid other cities dispose of its waste.

Hong Kong’s landfills will start overflowing as soon as next year (paywall); it already exports a lot of its recyclable trash. Its trash overflow is partly due to the fact that nearly nine out of 10 people live in buildings that are 10 or more stories tall. Shared garbage chutes and city-paid trash collection incentivize residents to produce more trash. Li Ka-Shing might want to consider some trash investments at home.