After the loss of Lahore to the newly-created Pakistan, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, envisioned the new capital of post-Independence Punjab as a city that would mark the beginning of a new era for the country.

“Let this be a new town, symbolic of (the) freedom of India unfettered by the traditions of the past…an expression of the nation’s faith in the future,” he said.

A futuristic city, then, was to be built in Chandigarh, near the foothills of the Himalayas—240km north of New Delhi. The location was chosen for its good water supply, moderate climate, and pleasant views. On Dec. 19, 1950, after the tragic death of the Polish architect initially chosen for the project, the Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, signed on to create the city’s masterplan.

Over the next decade, Le Corbusier and his team constructed Chandigarh from scratch, designing a meticulously planned city that stood in sharp contrast to the usual chaos of urban India. Le Corbusier “was insistent that it must be solely a seat of government, not of industry and manufacture: ‘One must not mix the two,’ he stipulated,” Sunil Khilnani writes in his 1997 book, The Idea of India.

Crucially, Le Corbusier agreed (paywall) to design the city for the relatively low salary of Rs2,000 a month (excluding expenses for whenever he made a trip to India, and a cut of the cost of any buildings he designed personally). And that made a big difference at a time when India was far from being the booming economy it is today.

With its array of Brutalist-style government buildings, grids of roads, self-contained residential sectors, and tree-lined boulevards and parks, Chandigarh was a significant, and sometimes controversial, experiment in urban planning that was observed with interest (paywall) in India and around the world. Decades later, its iconic Capitol Complex, which includes the state’s legislative assembly building, the secretariat, and the high court, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

However, over the years, a number of buildings have suffered neglect. Moreover, many important Le Corbusier-designed pieces, including manhole covers and chairs, have been taken away from Chandigarh, ending up at auctions in the West where they were sold for sizeable sums.

Now, the adaptation of Le Corbusier’s modernist architecture in India is the subject of a new book titled Chandigarh Revealed: Le Corbusier’s City Today by New York-based photographer and designer Shaun Fynn, published by the Princeton Architectural Press and Mapin Publishing in India. In his photographs, Fynn has documented the changing face of Chandigarh, capturing how a city initially designed for 500,000 residents, and now home to over a million, has evolved over the years.

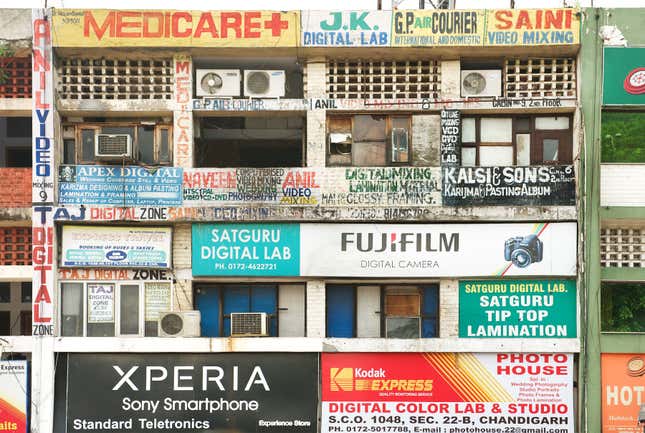

“Chandigarh remains fascinating today not only for the importance of Le Corbusier’s works but also for its patina of time and the changes that have shaped the city in ways he could never have foreseen,” Fynn, who once lived there, writes in the introduction to the book. “The rich legacy of Indian culture has emerged in the adaptation and decoration of buildings, and has imposed its own visual codes.”

Fynn notes that entreprenurial traders and shopkeepers have squeezed into the empty spaces left by Le Corbusier and his team, reinterpreting the city in their own way. Moreover, with tall buildings banned from the area, slums have emerged around the city to cope with the growing strain of an increasing population.

Here’s a selection of Fynn’s photographs of Chandigarh’s buildings today: