The Great Barrier Reef is in the midst of its fourth major bleaching event in the past 20 years, according to observations published Monday, and scientists are despairing. For the first time, the bleaching event immediately followed another the year before—which was the most widespread and damaging bleaching ever recorded on the reef.

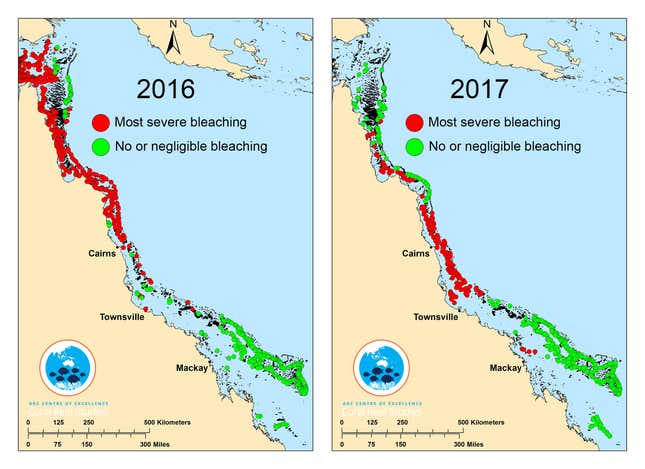

The 2017 bleaching event is mostly affecting the central region of the reef, while the 2016 bleaching was concentrated in the northern part. There are some areas that were affected in both years. Bleached corals are not necessarily dead, but the one-two punch of consecutive bleaching events all but seals a deathly fate for large swaths of the reef. Combined, two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef are in critical condition. The portion affected in 2016 is all but sure to die.

“It takes at least a decade for a full recovery of even the fastest growing corals, so mass bleaching events 12 months apart offers zero prospect of recovery for reefs that were damaged in 2016,” Terry Hughes, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, said in a press release. Hughes and his team conducted the aerial survey that confirmed both 2016 and 2017 bleaching events.

Rising sea temperatures driven by global warming are primarily to blame for the widespread and rapid degradation of the reef. Four mass bleaching events in the Great Barrier Reef have now occurred since just 1998; none had ever been recorded before that year. The 2016 event was the most severe.

Corals bleach when the water warms to a temperature above what they can tolerate. The stressed coral polyps react by expelling the algae that live on them—and which give coral reefs their color. Naked of their algae, the coral polyps become transparent, appearing white due to the calcium structure behind them.

But the algae is the corals’ main energy source—so without it, it starts to starve. This is a critical time period; if water temperatures cool in time, the algae could return and the reef could recover. If the warm temperatures persist, the chance of recovery goes down.

And to have a greater chance at recovery, bleached reef must be connected with healthy reef, so the reef can repopulate with new coral polyps. The rapidity of the bleaching, without much pause between events, does not leave much hope.

Other factors contribute to reef death, including water pollution—but global warming has eclipsed those factors in terms of devastation. Jon Brodie, a scientist who has spent his career on water quality issues affecting reefs, told the Guardian the Great Barrier Reef is now in a “terminal stage.”

“We’ve given up. It’s been my life managing water quality, we’ve failed,” Brodie told the Guardian. “Even though we’ve spent a lot of money, we’ve had no success.”