“Strategic patience.” It’s a phrase almost as infamous in the foreign policy lexicon as president Barack Obama’s “red line” or president George H.W. Bush’s “line in the sand.” And yet if “red line” is a connotation for America’s failure to meet a commitment and “line in the sand” connotes US military strength, “strategic patience” is a synonym for policy failure, ineptitude, and an inability of the most powerful nation in the world to bend a small, rogue, nuclear-armed nation to its will.

North Korea is the foreign policy crisis that never goes away. Every single policy option short of a preemptive military strike has been embraced by US officials to put the Kim dynasty in its box and limit its capacity to threaten its neighbors—and US military forces stationed in South Korea and Japan—with nuclear holocaust. Needless to say, none of them have been particularly successful in mitigating the threat. President Bill Clinton’s diplomacy with Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-il in the mid 1990’s provided a temporary reprieve, culminating in an Agreed Framework that shut down North Korea’s plutonium weapons program for about eight years. But diplomacy since then has been erratic at best; the Bush administration only got seriously invested in the process during the two years of its second term, and president Obama largely gave up once Pyongyang violated a missile moratorium in March 2012.

The strategic patience policy, solidified by the Obama administration, was a fancy way of saying that Washington would no longer be itching to talk with the North Koreans. The US was going to lean on China to get tougher on the Kim dynasty; missile defense would be beefed up and US-South Korean-Japanese intelligence and defense collaboration would increase; and Kim Jong-un would have to be serious about denuclearization before US diplomats would waste any political capital on negotiating. The approach sounded rough and resolute and should have been produced smiles on the faces of hawkish Republicans—in response to a 2016 offer from North Korea, president Obama waved it away, saying Kim would “have to do better than that”—but in reality it produced nothing of consequence. Pyongyang simply grew its program, continued to refine its ballistic missile technology, and continued violating UN Security Council resolutions every year. By the time Obama handed over the reigns to Donald Trump, one of the most respected nuclear physicists on the planet estimated that North Korea had “sufficient plutonium and highly enriched uranium to build 20 to 25 nuclear weapons.”

One can see why the Trump administration would want to do things a little differently.

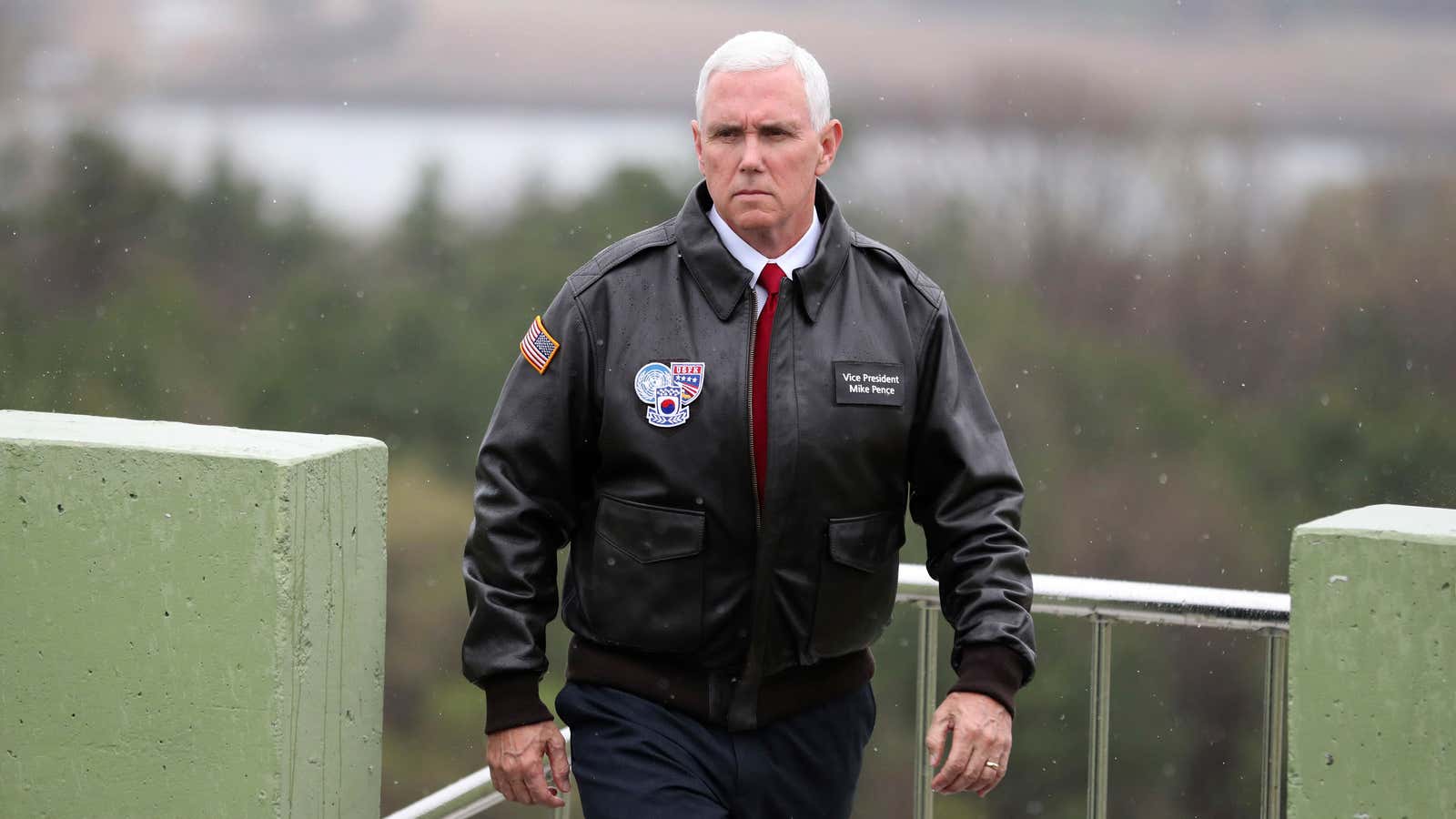

And indeed, secretary of state Rex Tillerson, vice president Mike Pence, and White House press secretary Sean Spicer have all hammered home the point that strategic patience is a thing of the past. Tillerson publicly stated last month that Washington has nothing to show for “20 years of a failed approach,” concluding that the US wouldn’t sit down with North Korean diplomats unless they would be wiling to eliminate their nuclear weapons program entirely. The “era of strategic patience is over,” vice president Pence declared during his first trip to South Korea. From the rhetoric, it sounds like the Trump administration is pursuing a 180-degree course correction from its predecessors.

And yet, there is very little evidence to date that would suggest that the era of strategic patience is in fact over. The two-month North Korea policy review that was recently completed by the National Security Council is essentially a continuation of the Obama administration’s North Korea strategy, but with more bellicose rhetoric attached. Speaking to the Washington Post, a senior administration official described the Trump policy as one of “maximum pressure,” whereby more stringent multilateral and unilateral economic sanctions will be implemented in an attempt to starve Pyongyang of the cash it needs to keep building its weapons of mass destruction program. Eventually, this reasoning goes, Kim Jong-un would have no plausible choice but to swallow his pride and dispatch his diplomats to new talks with the Americans. The goal, much like Obama’s, is the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. No short-term suspensions, missile moratoriums, or testing freezes will suffice.

This is a policy that Obama would could be proud of.

How exactly is the 45th president’s approach any different from the 44th president’s? If one takes away the blustery warnings to the Kim regime of Trump and his cabinet members, there really aren’t any differences at all. During his eight years at the helm, Obama hoped that the Chinese would shut down oil exports to Pyongyang, cut off coal imports, and decrease normal trade between the two nations. And now that Trump is the commander-in-chief, he’s hoping for the same exact thing.

The Trump administration may not want to admit it, but they are following in the footsteps of the strategic patience policy that the Obama administration established years before Donald Trump was even seriously thought of as a presidential candidate. Strategic patience is far from dead.