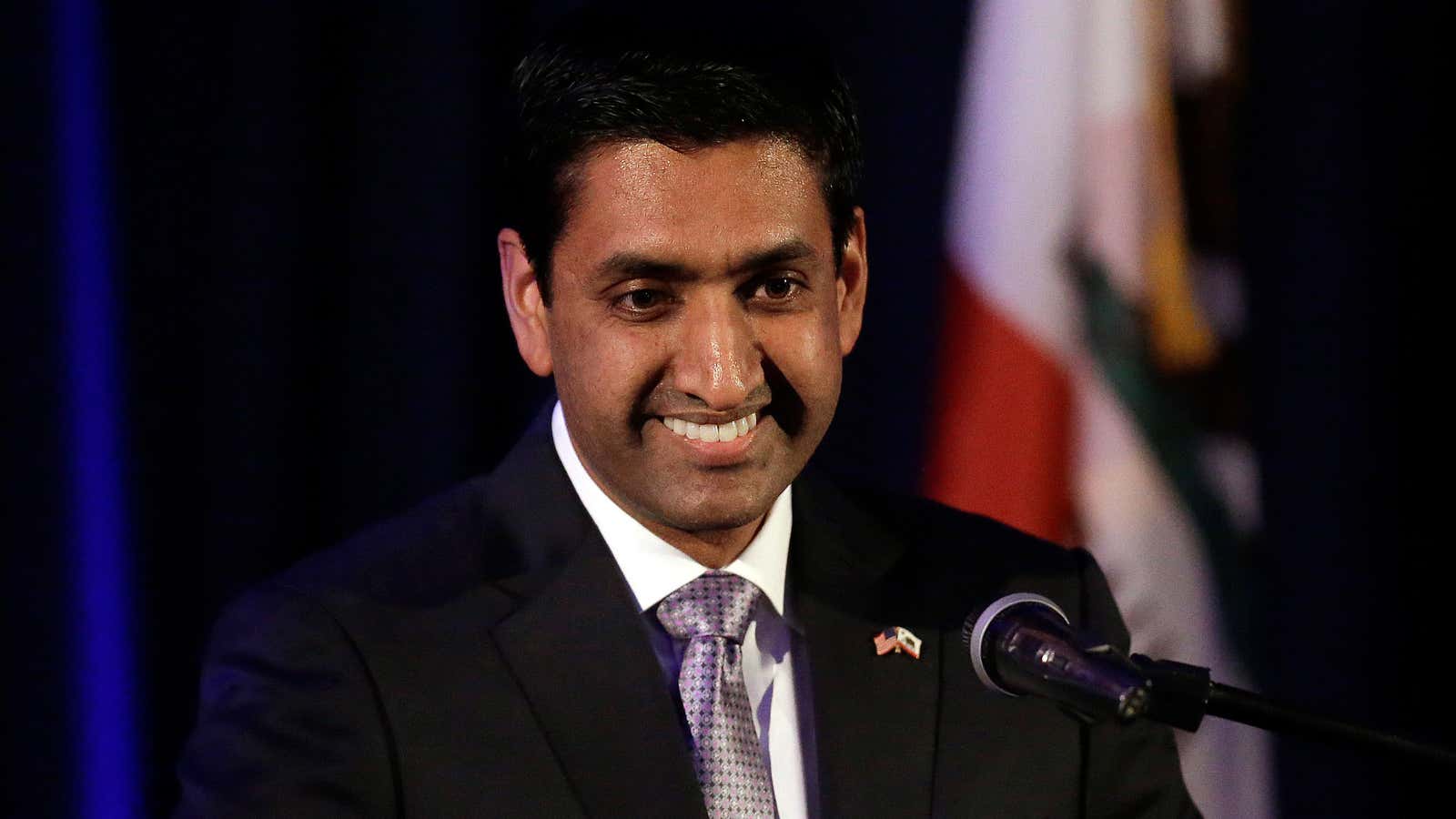

A newly elected democratic congressman from Silicon Valley has an ambitious alternative to the republican’s corporate tax cut: a giant negative income tax for the average American. Under Ro Khanna’s still-forming plan, the government would massively expand its existing annual income matching program, giving out roughly 60 cents for every dollar earned on the job, up to $6,000 for singles and $12,000 for families.

While this plan may appear like typical liberal welfare at the expense of corporate America, it may, in fact, promote greater job growth than giving giant corporations hundreds of billions of dollars in tux cuts.

According to the Kansas-based economic think tank, The Kauffman Foundation, high-growth startups—companies with double digit growth—account for a disproportionate share of net new jobs.

Kauffman research analyst Arnobio Morelix tells me this is because older industries tend to shed more jobs than they generate; now passed their most innovative period, established giants are focused more on making their existing business operations more efficient with robots and outsourcing (think Uber’s self-driving cars or auto manufacturers).

“US corporate profits have been robust, companies’ domestic cash reserves are high, and interest rates have been quite low,” explains MIT economist Andrew McAfee, author of the new book on automation, Machine, Platform, Crowd. “In short, US firms have not been hobbled by a lack of money to invest in, for example, new facilities. So I don’t see how a corporate tax cut would quickly and directly cause them to start hiring more.”

When asked about the possibility of an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit, McAfee was bullish on the idea: “The EITC is a direct incentive to enter the labor force, and to work more hours (up to a limit). The research is pretty clear that it works as designed. So I support expanding it: making it both bigger and available to more people”

After 2004, when America’s largest corporations were enticed to repatriate their overseas cash holdings with a generous a tax holiday, many of the tech giants ended up cutting jobs, according to a Senate report led by then-democratic chair Carl Levin. Hewlett Packard shed 8,000 US jobs. IBM shed 12,000.

Congressman Khanna’s plan will end up costing roughly the same amount of money the republican’s tax cut plan (between $1-2.5 trillion over the next decade, according to the Tax Policy Center, a nonprofit think tank).

Theoretically, a quasi-basic income in the form of a giant tax credit could give ramen noodle-fueled startup founders the economic security necessary to take risks.

During the course of the story, I reached out to several startup founders that had gone through the famous Bay Area Y Combinator entrepreneurship program, asking them about whether a tax credit of $6,000 would have realistically made any difference.

For many startup founders living in San Francisco, $6,000 wasn’t a whole lot of money. However, for middle America, it is quite a sum. For instance, YC Alum Jesse Vollmar built his own Michigan-based agricultural data analytics firm, Farmlogs, with just $500 in 2012. Though Vollmar says the company is set to double its workforce over the next year, most of his revenue gets plowed back into the business.

“For FarmLogs, the business demanded that we operate at a loss for the first few years. In that case, a lower tax rate would not have helped us at all and a tax credit would have,” he tells me.

That is, if scrappy startups are the future of work and growth in middle America, tax credits might be more pro-business than a tax cut.

Not everyone economist I spoke to, however, was convinced.

The American Enterprise Institute’s Stan Veuger told me that he wasn’t terribly optimistic that $6,0000 would be sufficient, especially since targeted tech policy might be cheaper. “I think more money for R&D, funding for high-end STEM training and research, and increased high-skilled immigration would be more effective,” he tells me.

The idea of massive cash transfers are a relatively under-researched idea; now that basic income is going from theory to policy, the details matter. It’s clear though that economists do not necessarily view corporate tax cuts as the only “pro-market” solution, especially in the age of automation and high-growth startups.

This is a major reason why the head of Silicon Valley’s Y-Combinator, Sam Altman, is starting to research the effects of basic income, with an experiment giving out unconditional cash in Oakland, California.

“I think there are new novelists that are right now driving for Uber that could contribute more to the sum output of humanity; there are great artists, there are people that just have new ideas about how to build communities that make people happy, that have nothing to do with tech or startups at all, but are currently not able to do what they want to do,” argued Sam Altman, at a Bloomberg talk last year.

Altman’s hunch about cash transfers is still a theory. But, as Khanna introduces his plan into the House Budget Committee later this year, it’s worth economists and his fellow democrats taking seriously.

Details of the revenue estimates are provided by Elaine Maag of the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, based off a plan first popularized by Chuck Marr, a finance expert at the Denver-based fiscal think tank, The Center for Priority Based Budgeting. In disclosure, Ferenstein helped craft Khanna’s policy, as part of on-going project to bring together congressmen and ideas from Silicon Valley together. The work was unpaid.