Rastafarianism is a religion, an idea, a sociopolitical movement, and an international pop culture phenomenon. For adherents, it’s a black-power Abrahamic faith with a reverence for ganja inspired by reefer houses of 1920s Harlem.

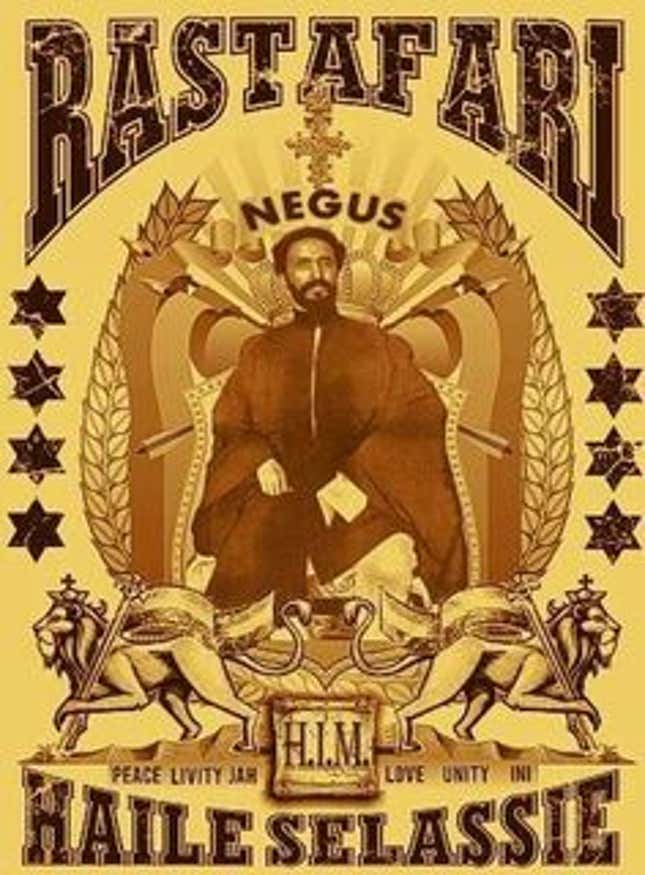

There are different strains of Rastafarian belief—it’s a necessarily loose and anti-authoritarian faith—but all identify symbolically with the twelve tribes of Israel and share one prophet: Ras Tafari, the given name of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I, crowned in 1930, the monarch of Africa’s only independent nation at the time.

His crowning fulfilled a prophecy, evidenced in verses in Psalms, believers say, that a king would come from Africa to lead black people everywhere—ultimately, to a return to Zion, the Promised Land in Ethiopia, which represents all of Africa. Some Rastas believe the emperor was a reincarnation of God, like Christ, and others that he was a destined emissary. Either way, the Ethiopian monarch is known to Rastas as His Imperial Majesty, or HIM, and revered universally.

The idea that the black king fulfilled a prophecy was supplied by Marcus Garvey and inspired by biblical verses. Garvey, a Jamaican writer and activist living in New York, began the black nationalist movement in the US. In 1928, he famously said, “Look to Africa, when a black king shall be crowned, for the day of deliverance is at hand.”

Leonard Percival Howell, a Jamaican preacher who worked in Harlem reefer houses as a teenager and then opened his own shop before being deported in 1932, was swayed by Garvey’s call but dismissed from the flock. Howell rented a space for his teahouse from Garvey’s organization in New York but the latter was alarmed by the reefer smoking and ejected Howell from his building and group.

Back in Jamaica (then under colonial British rule) Howell fused Garvey’s call for empowerment with a black Abrahamic faith he called “Rastafari”—not quite Christian, replete with Jewish symbols—and went door to door preaching to poor villagers and finding followers. For upper-class islanders, however, the religion’s disdain for the status quo was frightening. Howell was arrested and imprisoned in 1933 and his doctrine was deemed devilish.

He continued to write while incarcerated, and after his release in 1936 kept gaining followers. In 1940, the preacher established Pinnacle, a community of about 1,000 Rastas who followed a special vegetarian diet, shirking seasonings but for the sacred herb, marijuana. They grew ganja among their yams and greens.

In religious rituals, discussion groups called “reasonings,” they smoked cannabis, a holy weed which they believed grew on the grave of King Solomon and conferred wisdom. Howell preached that marijuana was encouraged in the bible, for example in Genesis 1:29:

And the Earth brought forth grass, and herb yielding seed after his kind, and the tree yielding fruit, whose seed was in itself, after his kind: and God saw that it was good.

What was not so good, in the eyes of authorities, was the fact that Howell’s people sold weed all over the island. In 1941, he was again arrested, this time in a raid on Pinnacle’s marijuana plants.

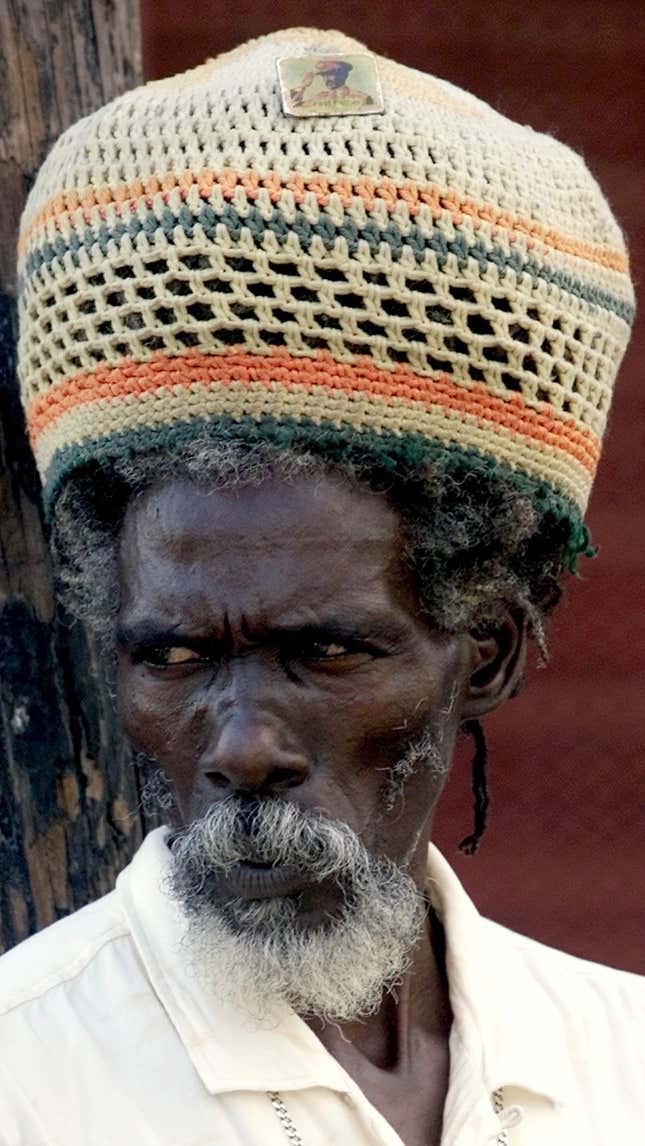

Some Rastafarians say that a group of Howell’s guardsmen grew dreadlocks then, to symbolize their warrior status. But there’s no proof of that, at least not in photos, and Howell kept his hair short after his release in 1943. Nonetheless, locks became synonymous with Rastafarianism and with fighting the power. Raids continued through the next two decades—but the religion persisted in spreading. In 1962, when Jamaica gained independence from Britain, Rastafarianism was gaining ground with people.

On April 21, 1966, came the big day for Rastafarians. That’s when their prophet, emperor Haile Selassie, returned to Jamaica. He was greeted by an overwhelming crowd of believers at the airport, and was moved, some say to tears, by their fervor. The Ethiopian monarch—a symbol of black power and freedom—refused to walk on the red carpet rolled out for him, walking on the ground instead like a common man to the delight of Rastafarians. On that visit, he honored the religion’s leaders, awarded them a land grant in Ethiopia, and helped to give them legitimacy in the newly independent nation. The Ethiopian never said he was their messiah, not publicly, but he also didn’t deny it.

Around that time, the man who would make Rasta go global was converting to the faith. Bob Marley, the charming emissary and musician, would, in the 1970s sell the world on reggae, dreadlocks, poetic political formulations in a Jamaican accent, and of course, marijuana.

On 4/20—when Americans celebrate cannabis—there’s likely to be lots of Bob Marley and the Wailers playing as spliffs are smoked. But Rastas don’t honor 4/20, despite their love of marijuana. So in the name of a musical legend and freedom itself, smoke the holy grass on 4/21, which is celebrated by Rastafarians as Grounation Day—the return of their prophet to Jamaica.

It is a tradition. As the Jamaica Observer reported last year, Grounation Day in 1966 was a momentous occasion, with ganja in the air and the authorities in a rarely forgiving mood about marijuana. “Man a smoke herb all over the place,” Rasta Michael Henry told the paper. “I hear a police seh, ’lef dem. Fi dem day dis’.”

In other words, people were smoking weed freely and even the cops said, “let them be just this one day.”

Amen. Respect.