With other democracies in flames, Japan is saying “no thanks” to change

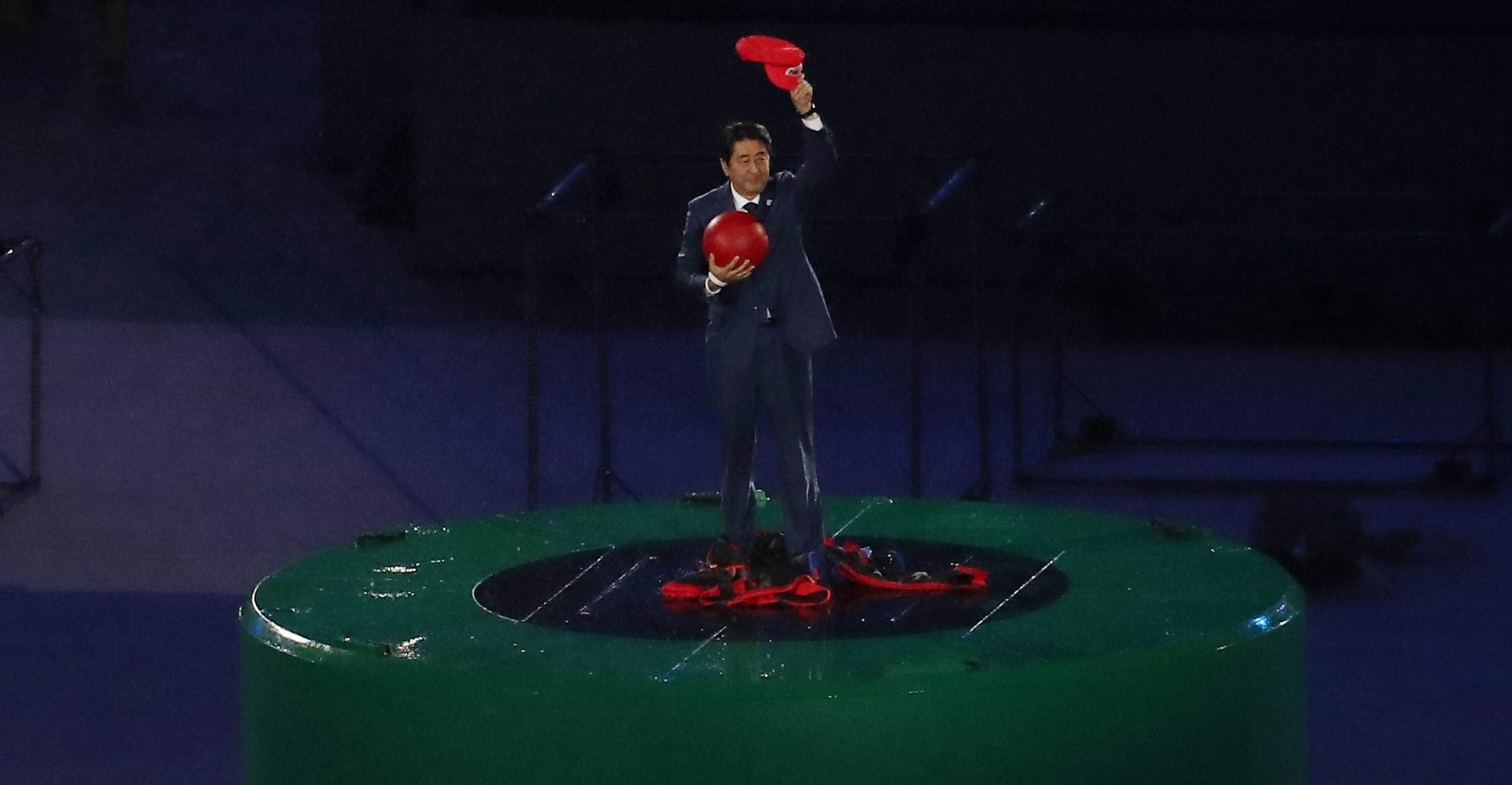

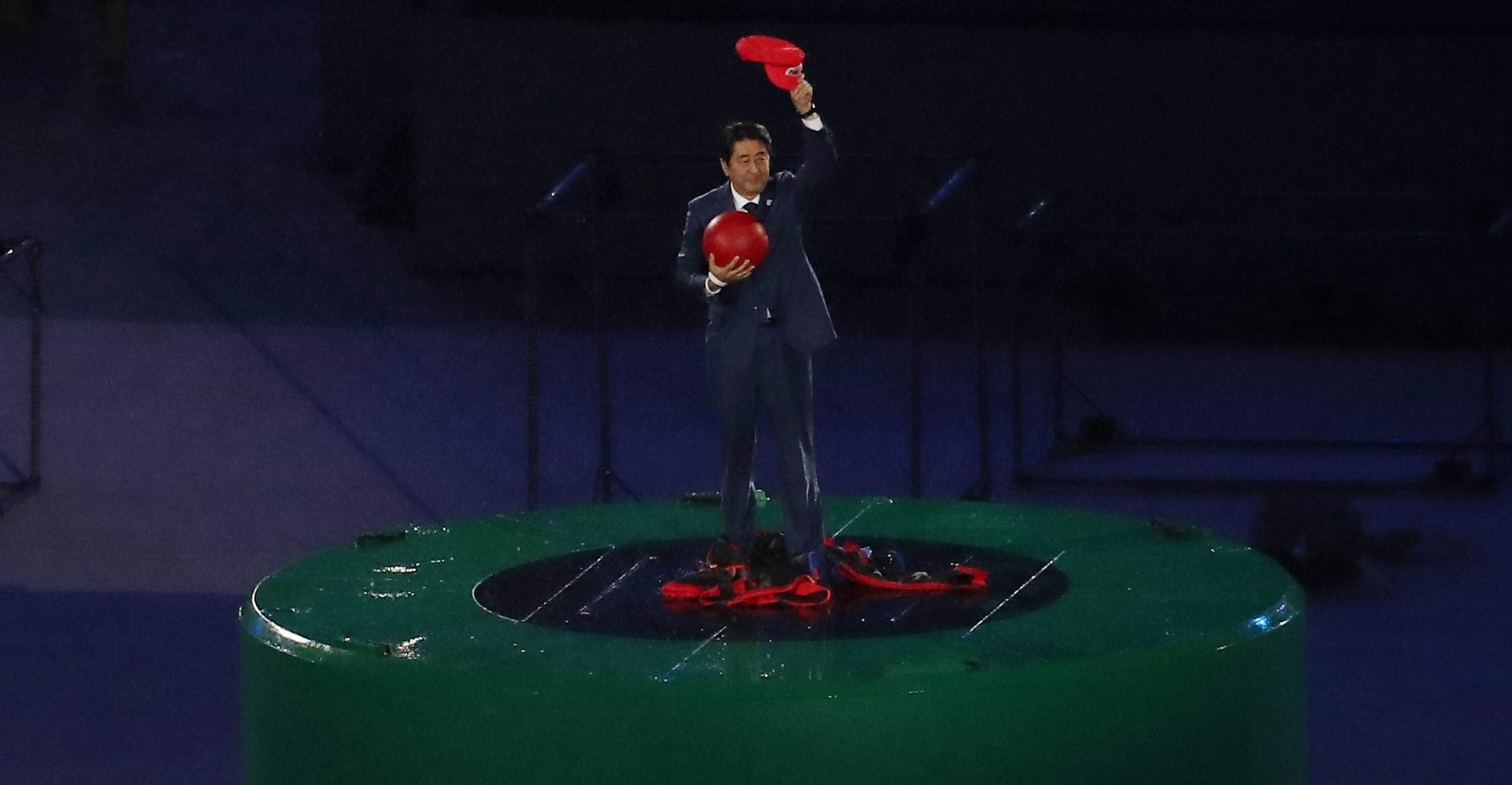

Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe made an appearance at last year’s Rio Olympics dressed up as Super Mario climbing out of a pipe. He is rarely that delightful or exciting.

Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe made an appearance at last year’s Rio Olympics dressed up as Super Mario climbing out of a pipe. He is rarely that delightful or exciting.

What he’s appreciated for in Japan is his steadiness, which is why his government consistently gets approval ratings of above 50%, a dream for any elected leader of a major world democracy.

No, his ambitious plan to reboot the Japanese economy, Abenomics, hasn’t yielded spectacular results. Yes, many are concerned with creeping nationalism and authoritarianism in his government policies. And indeed, Abe’s wife and his defense minister both are embroiled in a big scandal involving a far-right school operator, Moritomo Gakuen (paywall), that has taught children to be racist against Koreans and Chinese.

Still, Japanese people know that things could be a lot worse.

“His government has been so stable and pretty much every other advanced democracy looks so unstable… Voters aren’t even looking for him to shake things up,” said Tobias Harris, a fellow at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation in Washington DC. “After years of a revolving-door premiership, people are just happy there’s a stable pair of hands.”

Steady does it

Abe is now in his third term as prime minister of Japan. His first term lasted from 2006 to 2007 and his second from 2012 to 2014. Between the first and second, Japan cycled through five different prime ministers. The last leader in recent memory with such a lengthy tenure and high levels of support—and genuine popularity—was Junichiro Koizumi, the hirsute maverick who for a while seemed to be able to shake things up in Japan during his prime ministership from 2001 to 2006.

Abe is no populist, and he certainly lacks Koizumi’s dramatic flair. But he may be just what Japan needs at the moment. Across the sea, South Korea recently ousted its president and is without real leadership at a time when tensions are running high on the Korean peninsula. Nobody really knows what US president Donald Trump’s Asia strategy is, and so far Washington’s actions haven’t exactly inspired confidence (paywall) among its Asian allies. And in Europe, Japanese people see a continent that is racked by problems like terrorism, migration (of which Japan has little), and Brexit.

But polling shows that Japanese people are dissatisfied with the prime minister on a whole range of domestic issues. They are deeply unhappy with the way the government has explained the Moritomo Gakuen scandal, for example. The school operator was able to purchase public land in Osaka prefecture at a large discount to build a future school of which the first lady, Akie Abe, was supposed to be honorary principal. According to a poll (link in Japanese) conducted by the Yomiuri newspaper released on April 17, 82% of people did not find the government’s explanation of the land deal in the scandal convincing—the corruption allegations in question have gone far beyond the traditional type of structural cronyism that has been so prevalent in Japanese politics.

People also continue to feel pessimistic about the economy, despite attempts by the government to push through reforms relating to labor practices and women in the workplace. Other policies, such as restarting Japan’s nuclear reactors and Abe’s long-held dream to revise the pacifist clause in the constitution that restricts the military activities of the Self-Defense Forces, are also not popular.

Slim pickings

But there is simply no one else that voters can turn to. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has dominated Japanese politics almost continuously since it was formed in 1955, with opposition parties making only brief dents into the LDP’s monopoly on power. The Democratic Party of Japan’s (DPJ) last tenure in power from 2009 to 2012 was seen as a failure, and it is not something that many Japanese voters want to revisit.

“I would hesitate to call [support for Abe] ‘popularity’ because it’s too strong a term. Opinion polls indicate invariably that people support his cabinet because there’s no alternative,” said Koichi Nakano, a professor of politics at Sophia University in Tokyo. “That’s the number one reason.”

Many liberals are concerned about how powerful Abe has become. The media has been effectively muzzled from being critical (paywall) of his government. In a recent column, the Financial Times (paywall) argued that the Moritomo Gakuen scandal was the result of the practice of sontaku—a Japanese term referring to people who perform pre-emptive acts to ingratiate themselves to their superiors—which is the “a direct consequence of the way in which (Abe) has successfully consolidated huge individual power.”

Within the LDP, which functions as a collection of factions, there are whispers of a possible challenge from foreign minister Fumio Kishida at some point down the line, but Abe’s grip on power means that “he has no rivals in the political system,” said Nakano. Tokyo’s female mayor, Yuriko Koike, is immensely popular—not least because she has staked her career on standing up against the conservative cabal of men in Japanese politics—but it would be difficult for her to translate her local political power to a national level.

Better the devil you know

Meanwhile, the recent geopolitical chaos on the Korean peninsula has given Abe a further leg up.

“This plays right into Abe’s wheelhouse. Over 90% of Japanese feel threatened [by North Korea] to one extent or another. Abe made his name as a North Korea hawk,” said Harris. “If there’s one thing that he’s going to be good on, it’s standing firm against North Korea.”

Abe has made the resolution of North Korea’s abduction of Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s a priority for his administration. Earlier this month Japan extended sanctions against North Korea that have been in place since 2006.

The LDP recently revised its rules for term limits on party leaders, such that Abe could in theory run for another term and remain in power until 2021—meaning he could become the longest-serving prime minister in Japanese history. Some analysts cast doubt on whether even Abe could last that much longer in power, but at least in the near future, Abe is the devil that Japan knows.

“Japanese people do look at places like South Korea and Europe and shake their heads and say, ‘Compared to that we’re in pretty good shape,’” said Michael Cucek, an adjunct professor at Tokyo’s Waseda University. “‘We may not like individual programs that have been proposed, we may even think that Abe and his cronies do some self-dealing… But still, is it worth throwing everything off the side of the boat for trying out somebody new?’”