On the afternoon of May 26, 1987, a New Jersey state trooper doing routine stops on the Garden State Parkway pulled over a rental car carrying two men. The infraction was an open can of St. Pauli Girl beer, part of a six-pack from a nearby convenience store. When the window was rolled down, the trooper smelled marijuana. The driver admitted there were a few joints under his seat.

“Hands on the hood, feet back, and spread ’em,” the driver later remembered the trooper saying before he radioed for backup. Handcuffing the driver took two pairs of cuffs; he was a very big man. The troopers then pulled the passenger from the car and searched his bag. They found a vial of white powder. The passenger was arrested too.

They were taken in separate cars to the police station, where the driver was identified as James Edward Duggan Jr., better known by his professional wrestling identity, “Hacksaw.” The passenger’s ID said he was named Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri, but even the arresting officer recognized the popular World Wrestling Federation character The Iron Sheik. The powder tested positive for cocaine. But within a few hours Duggan was released, and so was Vaziri after signing an appearance bond. They returned to their car and continued southbound to Asbury Park, where they were scheduled to beat each other up before a crowd of thousands later that night.

The next morning Hacksaw called Vince McMahon, the WWF’s CEO (and sometimes in-story face of WWF management). “Jim,” said the voice on the other end of the line, “What have you done to us?

In the theatrical world of professional wrestling, Duggan was a “face,” short for babyface. He was a hero character—the wrestler the audience is supposed to root for. Despite Duggan holding a degree in applied plant biology, Hacksaw had a brawny, patriotic, good-ol’-boy persona. He often entered the ring carrying a two-by-four piece of wood and an American flag.

The Iron Sheik was a “heel”: the character the audience is supposed to root against. Vaziri had played a number of face characters, but he eventually found fame as a heel by adopting a heavy accent, growing an evil mustache, and wearing a vaguely Middle Eastern outfit. His gimmick was to antagonize fans with anti-American taunts before each match.

In the spring of 1987, the two characters were supposed to be in the middle of a feud: the Iron Sheik’s evil foreigner vs. Hacksaw’s red-blooded patriot. Just two months earlier they had faced each other in Wrestlemania III, a pay-per-view event that broke all previous attendance and revenue records. For the two mortal enemies to now get caught together, in the same car, without some type of in-story plot device to explain their friendly presence, was trouble.

The following week, the media was reporting that both actors had been fired for “drug violations.” “The ‘heroic’ Hacksaw and ‘villainous’ Sheik, who have been carrying on like mortal enemies in arenas across the country, committed the deadly misdeed of being caught having a good old time like a couple of buddies,” gloated the Chicago Sun-Times.

At a TV taping in Buffalo on June 2, McMahon issued a furious warning to the remaining wrestlers. Mandatory drug testing for cocaine would begin immediately—and faces and heels must shun each other in public. “This job is bigger than a six-pack and a blow job! Duggan and Sheik will never, ever work for the WWF again!” he shouted as he pounded the podium. It’s unclear if the CEO was speaking in or out of character.

Suspending your disbelief

The word “kayfabe” describes the pretense that pro wrestling is a sport, not a performance. While the etymology of the term is lost in the mists of early carny slang, to maintain kayfabe is to stay in wrestling character at all times, and to insist on the legitimacy of plot lines and trappings. At the time, kayfabe was the official policy for all WWF wrestlers, even though the choreographed nature of matches was an open secret. Without it, perhaps McMahon feared that the willing suspension of disbelief would dissolve.

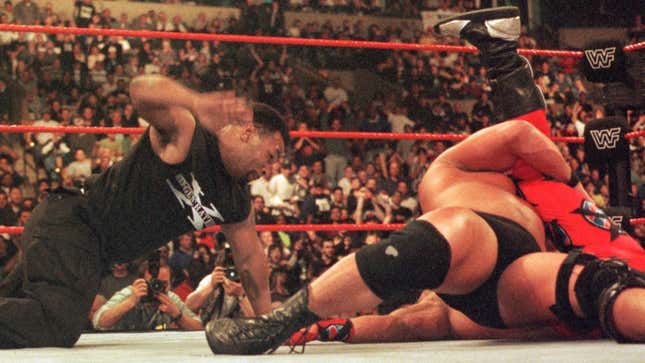

Modern professional wrestling shares its roots with early traveling-circus sideshows and burlesque. It’s a theatrical performance that combines scripted plot elements, improvisation, soliloquy, colorful characters, and over-the-top physical choreography. While there is a real sport called wrestling where the goal is to use grappling and holds to immobilize an opponent, early-on enthusiasts learned it was safer, and more exciting, to turn the wrestling ring into a type of stage where a carefully scripted performance of athleticism could take place

“Don’t they know it’s not real?” is the oft-repeated question. Of course the audience knows it’s not real—but what of it? When audiences see a magic show, it’s fun to pretend that the person on stage really is a sorcerer and to gasp at the miraculous feats they perform; it doesn’t mean the viewers truly believe that the laws of physics have been suspended. Pretending the action in the wrestling ring is real is likewise part of the experience.

In one recent incident, the notorious heel Triple H stopped in the middle of the show and broke character to go comfort an upset child in the audience. He gave the young fan a hug and ruffled his hair. “Hey, buddy, it’s OK,” he told the kid. “I’m just playing around.”

Wrestling fans who understand what’s going on behind the scenes are sometimes called wrestling’s “Smart Fans” or, by some, “Internet Fans,” since the rise of the internet has contributed so much to their proliferation. Smart Fans appreciate not just the spectacle of wrestling, but the technical, literary, and dramatic challenges that go into staging and performing such an over-the-top theatrical production. They analyze and debate the techniques behind the wrestling choreography. When a performer falls to the ground, Smart Fans look for the tiny blade he’s using to cut his forehead to make the damage look more convincing. It’s Smart Fans who follow the plot leaks and who know what will happen in each fight. It’s Smart Fans who know which feuds are scripted and which ones probably represent real animosity.

Smart Fans are such a part of pro wrestling that the sport has developed a number of tongue-in-cheek in-jokes just for them. Throwing an opposing wrestler through a table without massive bodily injury would be a ridiculous, nearly impossible move in real life. So at least once during most pay-per-view wrestling shows, someone gets thrown through the “Spanish Announcers’ Table,” a trick table set up for the purpose of shattering into spectacular splinters while the commentators run for cover. It’s a running gag to pretend there is a “safe” table to destroy, rather than allowing wrestlers to throw their opponents through the English Announcers’ Table (which is, assumedly, more sturdy). Wrestlers sometimes even feign confusion if the Spanish Announcers Table somehow makes it to the end of the match intact.

Which begs the question: If everyone understands that pro wrestling is a show, not a contest, what’s in it for the fans?

“The Smart Fans have this deeper aesthetic sense of, ‘Look at this guy, he’s bleeding now.’ You know that this is a staged event. We know that he willingly did that, and he’s doing that for us,” says Laurence McBride, who has spent years studying wrestling culture. “It’s almost moving, this sort of love for the guys who are willing to injure themselves quite dramatically. They’re like a network of people who go out there every month and put their bodies through these incredible performances for the show, as a gift to their fans.”

The power of cult branding

“Cultural dupes” is the phrase that Marxism assigns to consumers who desire an item solely for its surrounding context. According to the theory, consumers are like little children: They accept marketing claims at face value. They’re not sophisticated enough to realize when they’re being fooled. Consumers have no idea that their decisions are being manipulated for profit by those in control—people who wish to distract them from more important issues, like overthrowing the kaiser.

In espousing the cultural-dupe theory, Marxism, that most anticlassist of philosophies, perhaps betrays a little latent classism. It is condescending to assume that consumers only feel as they do because they don’t know any better. While fans do rely on branding—both internal and external—to inform their allegiances, they’re certainly not mindless puppets to it.

All fans are, at some level, Smart Fans. They understand that the objects they care so much about have been carefully constructed to appeal to them. Fandom entails choosing to buy into a context that is, at least partially, always fiction. Darth Vader isn’t really trying to take over the universe. The singer Johnny Cash wasn’t actually an impoverished and brokenhearted convict cowboy, no matter how many times he sang about it. We know that Oreos decided to launch an organic version of the company’s classic sandwich cookie because it saw an unfilled need in the marketplace, not because it suddenly decided that its customers deserved better ingredients.

Almost all fandom involves some form of making believe. Fans understand that they are being “duped” and they find value in playing along. As long as they are getting something important out of the relationship, fans are subconsciously making the decision, moment by moment, to ignore the inherent commercial reality of the products, celebrities, and media they love.

Blurring the line between real and not real, true and made-up, is the purpose of play. It allows us to imagine unlikely scenarios and say, “But what if?” Traditional wrestling—and car insurance, fast food, or many things that a marketer might want to sell—is a little boring. But playing with the audience’s concept of authenticity distances products from the adult rules that normally apply. The novelty of a mundane concept suddenly transformed into something new and delightful is a powerful engagement tool.

On a neurological level, when humans are confronted with an unexpected change in a familiar pattern, their brains experience a spike in dopamine, the happiness chemical. The more dopamine in our brains, the less we’re likely to get hung up on a product’s more potentially troubling attributes, such as how much money Vince McMahon is making off each bloody forehead and concussion. Playing with concepts of authenticity decommercializes a product and makes it safe for fans to personally identify with it.

Of course, encouraging an audience to pretend that there’s more to a fan object than just its monetary potential can be double-edged. Right now the self-deception serves a happy purpose. Later on, who knows?

Fandom results from a tenuous bargain. Fans choose to buy into a premise only as long as it serves their needs. They actively decide if, and how far, they’re willing to be duped. But no matter the level of loyalty a fan expresses for a fan object, the true loyalty lies with the concepts the object represents. They might like Hacksaw, the fun-looking character, but what they really bond with is his aura of patriotism and simple strength. These are two completely separate allegiances. Fans are willing to remain loyal to the thing they love only so long as they are not forced to confront its true commercial nature.

This tacit compromise underlies the outrage that occurs when a “feel-good” brand is accused of misconduct. Allegations of poor working conditions in factories owned by context-heavy brands such as Nike or Apple hit us hard, while the same allegation at, say, a paper mill or a copper-piping factory might not. Both Nike and Apple go to great lengths to cultivate an aura of excitement, self-improvement, and wealth. There is something inherently inauthentic about juxtaposing those feelings with reports of impoverished or underage laborers.

Authenticity is the glue that allows fans and fan-object owners, two actors with potentially conflicting motivations, to unite toward a single cause. Fans are complicit in—not tricked by—their own enjoyable self-deception.

On Feb. 10, 1989, WWF representatives testified to the New Jersey Senate that pro wrestling was “an activity in which participants struggle hand-in-hand primarily for the purpose of providing entertainment to spectators rather than conducting a bona fide athletic contest.”

In acknowledging the open secret, pro wrestling was finally choosing to be transparent about its use of artifice. They would never again be able to claim that wrestling was a sport, not a show. It was the beginning of a new golden age for pro wrestling; the nineties saw it become more popular than ever. Just two years after firing two of his top performers (over “drug violations”), McMahon had created a new wrestling, one that was even more in tune with the over-the-top athletic theater fans cared about. The fake veneer of competition was gone. Although there would continue to be occasional instances over the following decades, the golden era of kayfabe was over.

Adapted from Superfandom: How Our Obsessions are Changing What We Buy and Who We Are. Copyright © 2017 by Zoe Fraade-Blanar and Aaron M. Glazer. Reprinted with permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.