In a fanciful advertisement from 1956, a limber American housewife is spirited to Frigidaire’s “Kitchen of the Future,” where she delightedly pushes buttons, gazes at flickering screens, and twirls a rotating cylindrical fridge. She skips away for an interlude of recreation involving tennis, golf, and sunbathing, then returns to remove a fully baked—and frosted—birthday cake, candles lit, from a large glass dome.

“No need for the bride to feel tragic,” the voiceover trills. “The rest is push-button magic! So whether you bake or broil or stew, the Frigidaire kitchen does it all for you. Don’t have to be chained to the stove all day; just set the timer and you’re on your way!”

It’s exactly this promise that Taina Franke, a mother of two with a blonde ponytail and a wide smile, carried in a giant cardboard box when she showed up on my doorstep in Culver City, California one recent afternoon. Inside the box was the Thermomix TM5, a German mega-appliance that combines the functions of a high-speed blender, slow-cooker, mixer, food processor, digital scale, sous-vide machine, steamer, and smart phone. The $1,450 contraption won’t frost and light the candles on your birthday cake, but it’ll come damn close.

Since its launch in 2014, the TM5 has sold 3 million units around the world, without any traditional advertising or sales channels. Instead, the machine is peddled by direct-selling representatives like Franke—”consultants,” in company parlance—who are some 45,500 strong worldwide. In 2016, Thermomix did €1.3 billion ($1.5 billion) in sales—selling a Thermomix TM5 about once every 26 seconds and helping to make its parent company, Vorwerk, the fourth-largest direct-selling company in the world.

And yet chances are, if you live in the US, you’ve never heard of it. That’s because the Thermomix hasn’t been marketed here until now. And in a larger sense it’s because—as much as we love our appliances—most Americans don’t really cook anymore. At least, most of us don’t cook from scratch.

It’s as if we hit a fork in the road, back around World War II, when the executives at companies such as Swanson and Kentucky Fried Chicken first offered their pre-made meals as a solution to the problem of getting dinner on the table—selling the promise of family togetherness over supper without the trouble and time of food preparation.

In recent years Americans have doubled down on their aversion to cooking (or simply work too many hours to find the time), and that “kitchen of the future” we imagined in the 1950s simply never materialized. Instead, we’ve innovated madly around meal delivery, with Silicon Valley startups such as UberEats, Caviar, and Postmates bringing restaurant dinners to one’s doorstep, while Grubhub (which owns Seamless) averages about 324,000 orders per day. For those who want an approximation of the home-cooking experience, Blue Apron reportedly ships 8 million pre-portioned, ready-to-cook meals per month.

In the kitchen, America is a nation of extremes: Foodies happily cultivate their sourdough starters and cure their own salmon, while much of the nation could easily use their ovens for storage. Those of us in the massive gulf in between really seem to want to cook more. And as America’s wellness obsession and food allergies—or, at least, our awareness of them—are on the rise, so too is our desire to control every ingredient we put in our bodies.

Search for “healthy weeknight dinner” on Pinterest and you’ll find a bottomless well of cheerful, accessible recipes such as “15-minute honey-garlic shrimp” and “chicken-and-broccoli bowls.” But many of us still just order sushi or pizza on Seamless, then gobble it in front of aspirational cooking shows such as Top Chef or The Great British Bake-Off.

Into this predicament comes the Thermomix, like a gift from that Jetsons-like future that never came to pass in America, one where the problem to solve is still what to cook for dinner, and technology offers a solution. Is this what could have been, had we not taken the processed, pre-packaged, 30-minute-delivery bait? And will we spend $1,450 for a ticket to that alternate reality?

The executives, employees, and evangelical direct-sellers of Thermomix—Taina Franke among them—believe that we will. That’s why the company has hired 25 employees for its new US headquarters in Thousand Oaks, CA, and begun to recruit and train more consultants like Franke, in hopes of reaching nearly $9 million in US sales in 2017, and continuing to double that number each year for the foreseeable future.

What took it so long?

To call the Thermomix an international phenomenon would be an understatement.

Thousands of magazines, cookbooks, blogs, YouTube channels, and online forums are devoted to its life-changing use in Europe and Australia, where a Thermomix (known by the nicknames Bimby, Thermy, or Thermi) is a must-have for a certain kind of homemaker. The machine has even created its own influencers and niche celebrities. Stephanie Holtz—a German woman known as “Thermifee”—has become a YouTube star with her nearly 500 cooking videos starring the appliance.

In Germany—where Thermomix has been compared to Apple for both its design chops and fanatical customers—a portrait-style photograph of the machine covered the weekly news magazine Wirtschafts Woche, with the headline “Thermomania: How a kitchen machine stirs the Germans.” In Portugal in 2013, two years after the country defaulted on its debt, people purchased more than 35,000 Thermomixes, with price-tags nearly double the monthly minimum wage.

Rather than updating its machines with new models every year or two, Thermomix can take a decade to develop and release a new one—which is just what it has done for the TM5, released 10 years after the TM31. The new edition’s unannounced release in 2014 struck some devoted fans as an ambush. In Australia, where some 300,000 kitchens housed a Thermomix as of May 2016 (and my own brother-in-law jokes that his family’s would be the first thing saved in a fire), it sparked headlines such as “Outrage in the suburbs at stealth release of new Thermomix model” and “Thermomix War: Whose side are you on?”

There, the device has been popular enough to provoke both parody and backlash. In a delightful episode of the Australian comedic cooking video series The Katering Show, hosts Kate McCartney and Kate McLennan introduce the machine to their viewers, calling it a cult for those who “don’t have the energy for the group sex.”

What, actually, is this thing?

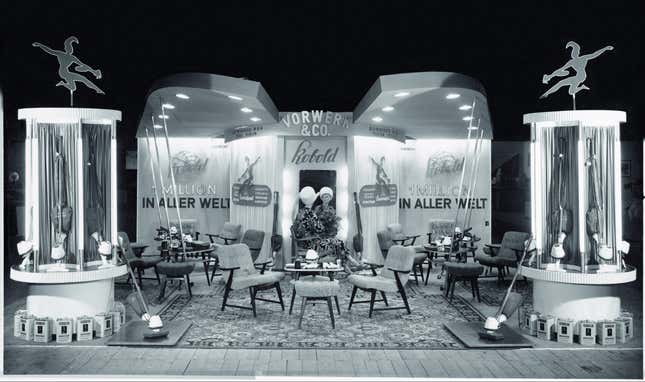

Back in 1883, two brothers in the northern Rhine of Germany, Carl and Adolf Vorwerk, founded a carpet manufacturing venture which grew to sell looms and develop patents for weaving technology. In the 1930s, Vorwerk expanded to include Kobold—first, a line of vacuum cleaners (some with innovative attachments for hair-drying and horse-grooming), and later household appliances such as refrigerators and washing machines.

In the early 1960s, Vorwerk introduced a food processor to its offerings, with features that included kneading, grating, and chopping. In 1971, the company added heating to its food processors’ capabilities. Some versions of company lore attribute the development to a general manager in France who was inspired by the local penchant for thick soups. Others credit a German mother who wanted to simultaneously cook and grind baby food. Regardless, this seemingly simple merging of features is still woefully rare, even in food processors today.

For the years to follow, the Thermomix chugged along modestly in the European market, with a new model emerging about once every ten years.

Then, in 2004, the company released the TM31. For the first time, the Thermomix boasted buttons instead of dials, a digital display, an expanded two-liter bowl, and new functions that included a reverse mode for stirring with the back of the blender’s blade and a temperature indicator. This new contraption soon started to build a niche fanbase on the internet, where the company nurtured an online community for customers to share recipes, cooking tips, and stories of kitchen victory.

This all perpetuated what Kai Schäffner, Vorwerk’s CEO and the leader of Thermomix’s US expansion, calls the “emotional loading” of the Thermomix. As he tells it, the Thermomix’s ability to transform amateur, insecure, or simply overworked cooks into highly adept chefs and hosts created a sense of devotion that extends beyond the product, to its community of users.

“What you get back from your family or friends when you cook for them is the appreciation of what you have done,” said Schäffner, an animated man with silver-flecked brown sideburns and the Swiss-German accent of an Austin Powers villain. “So most of the love goes back to the cook, not so much to the product, but that was a very strong emotional loading, and that also transferred back to the person who sold it to you.”

This army of sales people—the enlightened, energetic, and enthusiastic army of un-harried home cooks who sell the machine—create the feeling that you too, could join their ranks. Put another way: “It really became a cult,” Schäffner said.

Welcome to America

We Americans may have a complicated relationship to cooking, but we’re suckers for kitchen appliances. When it comes to cutting-edge technology, status symbols, and cult-y, covetable design objects, there’s no place quite like the well-appointed American kitchen, with its brand-name appliances. Growing up in the Midwest in the 1980s, it wasn’t just a food processor my mom used; it was a Cuisinart. And she didn’t just use a stand mixer to make cookie batter; it was a Kitchen-Aid.

In the 1990s, Americans had a short-lived affair with the automatic bread-maker, reportedly purchasing more than 3 million machines in 1993 alone. Twenty years later, foodies are splurging on $200 sous vide immersion circulators, and Saturday Night Live parodied our passion for $650 Vitamix blenders. Now, we’re all about the Instant Pot—a Canadian-designed electronic multi-cooker that was the top-selling item in the US for Amazon Prime Day in 2016 (excluding Amazon’s own products), a global shopping event which moved 215,000 Instant Pots in a single day. It was a US top-seller again this year.

Americans spent an estimated $9 billion on small kitchen appliances in 2016, according to the market research firm Euromonitor. As of 2014, one in five Americans had a device that connected to the “internet of things,” making us early adopters of internet-enabled home appliances we can control with our smartphones. Our deep desire (and pockets) for high-tech devices that promise health and convenience most recently willed into existence the farcical Juicero, a $400 juice-packet-squeezer that raised $120 million in startup capital—and was proven to be no better at squeezing its juice packets than a pair of human hands.

It’s strange, when one pauses to consider the potential, that there isn’t already a Thermomix in every suburban subdivision. This is America, and we are here for this.

Until 2016, cooks in the US couldn’t easily buy a Thermomix, because of restrictions due to certification and voltage. But that’s all changing with the TM5, Thermomix’s first foray into the digital era. For the TM5—which was designed specifically with the US market in mind—Thermomix not only got international certifications for all its plastic, steel, and electronics, it created a web platform that’s supported in 13 countries. This allows users to generate shopping lists and download recipes directly to their machines, which will walk them through the steps of preparing them.

This design doesn’t just reflect how digitally savvy and intrepid we Americans are at home; it reflects how inept we’ve become in the kitchen—a fact that hasn’t gone unnoticed by Thermomix.

“A lot of Americans do not know how to cook anymore,” said Schäffner. “This is a huge advantage, I think, that will come out over the next five to 10 years.

Unboxing the kitchen of the future

I welcomed Franke into my kitchen for my Thermomix “cooking party” (which is what consultants call their demonstrations). Like many of Thermomix’s early adopters in the US, Franke—originally from Germany—is an expat. She introduced herself, disarmingly, as a “cooking dyslexic” and handed me a postcard that read “ThermoTaina”—also the name of her website—with a picture of her opening the Thermomix bowl to reveal a pale pink concoction to her two smiling sons.

Franke placed the base of the Thermomix on my counter and plugged it in. About the size of a fancy cappuccino maker, it has a touch-screen that shows dials indicating the time, temperature, and speed, and a knob to control the blender speed. We’d be making a dish called “Chicken Pizzaiola,” she announced.

Franke fitted the steel 2.2-liter blender bowl onto the base, and dumped in a pre-measured container of white cheese blocks. She set the machine’s speed and time, and turned the knob. Two little towers of lights on the Thermomix’s face turned green. The machine roared to life, shuddered briefly, and pulverized the cheese blocks into shreds. After removing the cheese, Franke dropped in some onion halves and garlic cloves, which the Thermomix chopped and then sautéed with olive oil right there in the blender bowl, adding heat and a slow stirring speed. She poured in a can of tomatoes, set the time, temperature, and stirring speed, and simmered the sauce for 25 minutes.

But that’s not all. In the space between the sauce and the top of the bowl, she fitted a basket of fingerling potatoes to cook in the steam heat of the simmering tomato sauce. And above that, she placed the Varoma—a wide, saucer-shaped steaming bowl with a fitted lid—in which she laid boneless, skinless chicken breasts, side-by-side. I think there may have even been some cauliflower on the very top.

“I never waste steam,” said Franke.

After everything was cooked, the chicken breasts went into a casserole dish where they were covered with the sauce and grated cheese, then finished the old-fashioned way with 10 minutes in a hot oven. Depending on your point of view, this might seem ingenious, efficient, unappetizing, or just plain gross. (Steamed skinless chicken breasts?) It struck me as all of the above. That said, it is home cooking—and a dish that a busy parent might easily throw together on a weeknight.

And the machine is impressive. The four-pronged blender blade, designed to ensure an even chop, is terrifyingly heavy, sharp, and easily removable. The lid’s detachable center can also serve as a measuring cup for adding more broth to a slowly stirring pot. A spatula is designed to clean between the Thermomix’s blades and to hook onto the simmering basket as a handle. There is no BPA in the plastic, and with the exception of the base, the whole bloody thing can go in the dishwasher. And the simple instructions on the display screen leave little room for error.

“What I love is I can turn off my brain,” said Franke, just as it occurred to me I might never remember how to make that spatula act like a handle again. “It’s like hands-off cooking.”

Home alone with the Thermomix

If Chicken Pizzaiola had been my first impression of the Thermomix, I probably would have lost interest.

But I had learned about the machine several years earlier from my sister, Sara, who is married to a farmer in Western Australia. There, she is responsible for feeding her three kids, husband, and a rotating cast of workers and visitors who frequent the farm.

Suffice to say that Seamless is not an option—and she spends a lot of her time in the kitchen. When I visited in 2012, Sara’s Thermomix (the cult-classic TM31) never left the counter. She used it to make porridge, rice pudding, a velvety, cream-less cauliflower soup, and dough for many loaves of grainy homemade bread that became toast with morning tea, and sandwiches for school lunches. In the years since, she’s added dhal and risottos to her regular rotation, as well as countless soups.

After my demonstration with Franke, I kept the machine for a couple weeks of testing, and found myself increasingly convinced as the days wore on—not because I could cook “like a chef,” but because it made basic, elemental dishes not only easier, but better.

The first thing I made was oatmeal, and I made it pretty much every morning thereafter, because it was that delicious and simple. I know oatmeal on the stovetop isn’t exactly challenging, but with the Thermomix it was creamy, required zero stirring, and didn’t stick to my saucepan.

When Passover came and the grocery store was out of matzo, we used the Thermomix to knead dough for our own. Kosher? No. But it was outstanding. Soft-boiled eggs were also revelatory, cooked in the simmering basket for 12 minutes to my precise fudgy-yolked liking. I ate them with bowls of brown rice, cooked to perfection in the Thermomix, and drizzled leafy, oil-topped, Thermomix-ground salsa verde on the top. The machine also blitzed perhaps the best margarita I’ve ever had.

Toward the end of my stint with the loaner Thermomix, I pulled together a dinner of pea shoot-topped risotto with lemon, white wine, and parmesan in about 20 minutes, while I gave most of my attention to a phone call. The next day I reheated it for lunch, pouring the leftovers into the parchment-lined Varoma and steaming it over the blender bowl. After a few minutes, I cracked open the lid to release a puff of aromatic steam and found my reheated risotto to be neither dried-out, nor gluey. Frankly, it was Instagram-worthy. It occurred to me that a person could get used to this.

Depending on one’s needs, confidence, and creativity, the Thermomix is a highly adaptable piece of machinery—and in the hands of a chef, it really shines. ”It’s designed to be a one-stop-shop for people who don’t know how to cook,” said the Los Angeles-based chef, Kris Morningstar. ”However, just like the sous-vide method, put it in the hands of people with a higher skill level and the world’s kind of their oyster.”

“I’d heard of Thermomix for years,” said Morningstar. “I’d seen them on videos, on the internet. Every once in a while you’d hear of some American chef bringing one—you know, smuggling one back in from wherever they came from, but they were a rarity, much the same way that [sous-vide] circulators were at the beginning.”

Morningstar had his first go with the TM5 when his friend Ilan Hall, of Top Chef fame, asked him to compete in a cook-off sponsored by Thermomix. The company gave Morningstar a machine two weeks in advance, and let him keep it as a reward for his participation.

For the event, he developed two recipes: a chicken-liver mousse made completely in the machine, and a Mexico-inspired dish that made use of the Thermomix’s multiple layers, pureeing and cooking pumpkin seeds, hoja santa, and green chiles for a molé-style sauce in the blender while steaming a fish on top. At the time, not knowing the price of the Thermomix, he estimated it to be $3,000 piece of equipment.

“I think the benefit far outweighs the price,” he said, describing the way he can dump all the ingredients for a crème anglaise into the blender bowl, set it at a temperature that won’t curdle the eggs, and come back ten minutes later to find it perfectly thickened.

But Morningstar said his real “aha” moment with the Thermomix was at his former restaurant, Terrine. One night, the kitchen found itself short of couscous for a staple menu item, and Morningstar decided to give it a whirl in the Thermomix. Using the machine’s reverse blade function, which uses the dull edge of the blender blade to stir the contents, he prepared ten orders of couscous in under 20 minutes—a feat that would have easily taken him an hour the old-fashioned way.

But will it make Americans cook?

Celebrity “slow food” advocates such as Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman, the New York Magazine columnist (formerly of The New York Times) and author of the How to Cook Everything book series, argue for home cooking as a panacea for everything from America’s galloping obesity epidemic to alienation within families.

But when I asked Bittman whether he thought the right mega-appliance could make Americans cook more, he was skeptical.

“Why don’t people cook more?” asked Bittman. “It’s not for lack of technology… I think that people buy appliances much in the same way that people who don’t exercise buy gym memberships, or buy running shoes. They think, ‘Oh if I go out and buy a new pair of running shoes, then I’ll start running.'”

Some of those people, of course, do start running, but a lot of them leave their shoes in the closet, or just wear them to brunch. “At some point you have to become a person who exercises; You have to become a person who cooks,” said Bittman. “And although these things can make it easier for you, just like having a gym that’s in your building or two doors down makes it easier for you, they still don’t make you do it.”

Michael Ruhlman, the author of some twenty books about food and cooking, agrees that the Thermomix might not be the “everyman’s” machine it’s currently marketed as—at least not in the US.

“We’re cheap and lazy,” said Ruhlman. “I’m very skeptical that Americans will spend this kind of money on it, and have the energy and stamina to figure this out and stick with it.”

The data backs him up. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Americans devote more than 40% of their annual food budgets to restaurants and takeout. And when we do go to the grocery store, the categories we spend the most on include packaged and prepared foods and beverages—whether frozen burritos, jars of baby food, pre-portioned baggies of almonds, or bottles of soda. Americans spend less time cooking per day than residents of any of the other wealthy countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. In 2015, Americans said they spent an average of 36 minutes per day on food preparation—slice that data to look at people between ages 15 and 24, and the time spent on food prep and cleanup drops by more than half.

There is a simple paradox at the heart of this very complex machine, six decades in the making, Ruhlman pointed out. “If we learned the basics of cooking, then people would realize that cooking a meal is not all that difficult,” he said. “So why do we need this complicated machine to do something that is fundamentally simple?”

Even J. Kenji López-Alt, a kitchen tech obsessive and the managing culinary director at Serious Eats (which syndicates content via the sous vide company Anova) threw water on the notion that the future kitchen of our dreams has arrived. “The Thermomix and sous vide cookers and microwaves and skillets are all just tools, and all tools have limitations,” he said. “None of them are a magic bullet that’s going to cook everything for you.”

Marketing “the magic of Thermomix”

Nevena Srebeva, Thermomix’s director of sales in the US—a Bulgarian-born mother of two, who moved her family from New York to California for her job with Thermomix after 15 years at Avon—would beg to differ.

“It transforms the way you cook. It transforms your daily life,” she told me, with great conviction. “This is the power and the magic of Thermomix.”

Like Srebeva and Franke, when the international enthusiasts of the Thermomix espouse its virtues, they tend to speak in terms of “the movement,” “revolution,” and “magic.”

“It is the future of cooking,” said Srebeva, describing the perfect storm of smart home technology and health obsession that’s primed the US market for the Thermomix where, for the first time, customers are able to bypass the representatives and purchase a Thermomix online.

But first they have to find out about it. ”It is all about right now, building brand awareness here in the US,” said Srebeva.

Thermomix doesn’t pay for traditional advertisements, so it depends heavily on word-of-mouth to build that awareness—not unlike the Canadian maker of the Instant Pot, the pressure cooker that’s currently sweeping the US. Rather than paying for ads in magazines or on television, Instant Pot reportedly sent free appliances to 200 food bloggers and cookbook authors, planting the seeds for a social media blitz.

Thermomix is similarly courting US food-world influencers, but it sees its customers as its best ambassadors. It works hard to cultivate them, providing ongoing support via cooking classes, its recipe platform (which already has more than 20,000 recipes), and forums for recipe-swapping. This community element has been baked into Thermomix’s DNA since before social media permeated our lives, and now thanks to the Instant Pot, the US market may be ready to join the movement.

And yet, it’s gotten off to a slow start. When I called Mark Bittman and Michael Ruhlman for this story, neither had tried a Thermomix. (Send these guys a demo unit, Thermomix!) Ditto for the editors at the influential home-cooking resource, Food52, aside from editor Amanda Hesser’s brief dalliance with a previous model a dozen years ago. Thermomix has hired recipe developers to create regular collections to feed the online platform that syncs with the machines, but two introductory cookbooks for the US market are filled with the sorts of recipes a parent might have sent their child to college with 30 years ago: stir-fried vegetables, quiche Lorraine, and salmon in mushroom cream sauce.

Come to think of it, they’re just the sorts of dishes the forward-thinking housewife in that 1956 retro-futurist “populuxe” film might have dialed up from her “kitchen of the future.” Just like Franke said, a person could pretty much disconnect his or her brain from this whole process if they wished.

It’s as if in our desperation to cook dinner from scratch in our own kitchens, we’ve created a miniature, personal, industrialized meal factory. Which might lead a person to ask: Is that really so superior to ordering takeout? What if someone told that 1956 housewife she could request refreshing furikake-topped poké bowls or Tuscan kale-and-roasted-yam salad for her family, directly from her cell phone, no kitchen required?

The thing is, that for many members of the “aspirational class,” those Americans who spend their discretionary dollars on things like Pilates instructors, nannies, and organic cotton t-shirts, cooking dinner for their families the old-fashioned way isn’t a choice they make out of necessity. It’s an aesthetic one that they connect to their values and identities—like carrying an NPR tote bag. For many of us, especially those who fork over big dollars for high-end kitchenware, cooking is a leisure activity, a luxury rather than a necessity.

These are the foodies that would conceivably spend $1,450 on a kitchen appliance, but Thermomix clearly has a ways to go in winning them over.

When I last spoke with Meredith Petran, Thermomix’s head of US marketing, she said the company had recently partnered with Instagrammers in New York and California, including the Williamsburg, Brooklyn-based photographer, Molly Tavioletti, and LA food stylist and cook, Amanda Frederickson. She emphasized they’re starting small, to continue to support customers as the US market grows, but also mentioned that she dreams of getting a Thermomix into the kitchen of swimsuit model-turned-Instagram star and cookbook author Chrissy Teigen.

As for me, as I work from home after sundown, I hear my boyfriend operating the food processor in the kitchen, where dishes pile up and the oven beeps along with the timer on our Google Home. Leftover turkey burgers, baked zucchini sticks, and a cauliflower purée are on the menu. I’m sure they’ll do the trick, but I can’t help thinking how easily the Thermomix could help him whip up that pea shoot risotto.