In 2002, the openly anti-Semitic French far right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen shocked the world by reaching the second round of his country’s presidential election, with 17% of the first round vote.

Spontaneous protests of tens of thousands of people erupted across the country the day after the vote took place. A week later, one million horrified French citizens took to the streets, turning traditional May 1st workers’ rallies into anti-Le Pen protests. The far right leader was then demolished in the second round—improving his share of the vote by less than one percentage point—as the country rallied behind center-right opponent Jacques Chirac.

In 2017, however, Marine Le Pen—who kicked her father out of the Front National and toned down some of the organization’s most incendiary rhetoric, especially regarding Jews—took 21% in the first round and will advance to the final round in May. In contrast with 2002’s results, and the main reaction from markets, citizens, and politicians seems to have been relief that she didn’t come out on top in the first round. May Day is still a few days away, but so far reported protests have been far smaller gatherings of young people, including many anarchists and violent anti-fascists. (Plenty of Le Pen’s most virulent protesters also oppose her centrist opponent Emmanuel Macron.)

We’ve seen the far right pick up larger and larger chunks of votes in elections from Britain to Holland to Poland over the last decade. But photos depicting how the French reacted in 2002 versus how they reacted in 2017 show just how normalized this country’s political state of affairs has become. The massive outpouring of shock and indignation from 2002 has given way to dramatically smaller pockets of mindless violence in 2017.

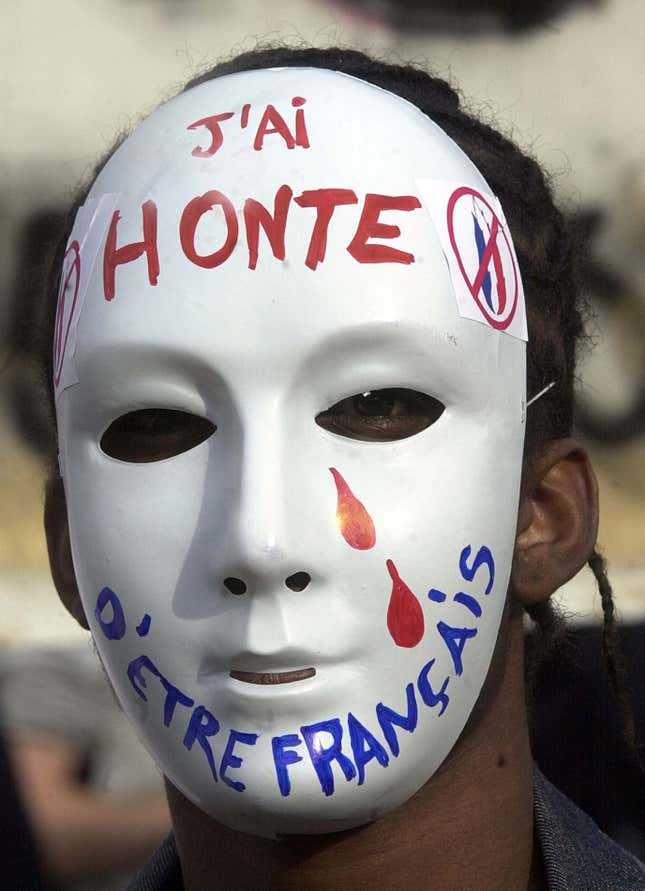

2002: Mass protests and mass shame

Shame and defiance were the overwhelming emotions.

On May Day, around a million citizens hit the streets.

2017: Anger among radicals and school students but no surprise

French media reported that several hundred “militant antifascists” (link in French) faced off with riot police in Paris in the aftermath of the first round of voting.

Young people burned garbage and smashed windows.

In fact, in the eyes of swathes of high school students who took to the streets on April 27 to oppose both candidates, Macron’s past as a banker and advocate of global capitalism makes him just as odious as Le Pen’s far right nationalism.

It is possible that thousands of regular voters will once again show their anger on May Day. But as of right now, images of Le Pen’s opposition are mostly dominated by radicals who seem to care less about voting her out of office than they do about breaking windows.

Meanwhile, Le Pen herself has no trouble attracting hordes of flag-waving supporters to her rallies.