Hosts of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner have one of the toughest gigs in comedy. They have to find a genuinely funny way to skewer the current administration while their target—one of the most powerful individuals on the planet—sits arm’s length away.

When Daily Show star Hasan Minhaj steps up to the mic April 29, he won’t have that particular awkwardness, as notoriously thin-skinned president Donald Trump is skipping this year’s festivities in favor of a rally in Pennsylvania. But the audience watching online and on C-SPAN can be a dangerously tough crowd, too.

The US public is at times a touchy bunch when it comes to political comedy, and is not afraid to escalate complaints. A Scottish comedian named Brian “Limmy” Limond made an off-color joke in January about Trump’s inauguration and was flooded with angry replies from the US, some of which claimed to have reported him to the FBI.

In some cases, those become the basis of a formal investigation against the person who made the joke.

In October 2016, journalist Nick Baumann made a joke on Twitter about voter fraud. Baumann’s Twitter joke was actually a reference to a previous Twitter joke by a user called @randygdub. So many news outlets indignantly reported @randygdub’s joke about tearing up mail-in ballots as fact that the US Postal Service issued a statement confirming that @randygdub did not work at a post office and this did not happen.

Days after his tweet, Baumann got a call from an FBI agent informing him that he was under investigation “because of the nature of what [he was] saying.”

As of December, the investigation was still ongoing. Baumann told Quartz that he doesn’t know the current status, as the agency has not responded to his FOIA requests. Baumann contacted @randygdub to ask if he had heard from the FBI; he had not.

So what kind of humor does attract the attention of America’s G-men? Most investigations in the last 25 years remain classified. But the FBI’s suspicion of popular culture stretches back decades, and the agency’s declassified files contain a wealth of complaints from Americans about jokes they believe went too far.

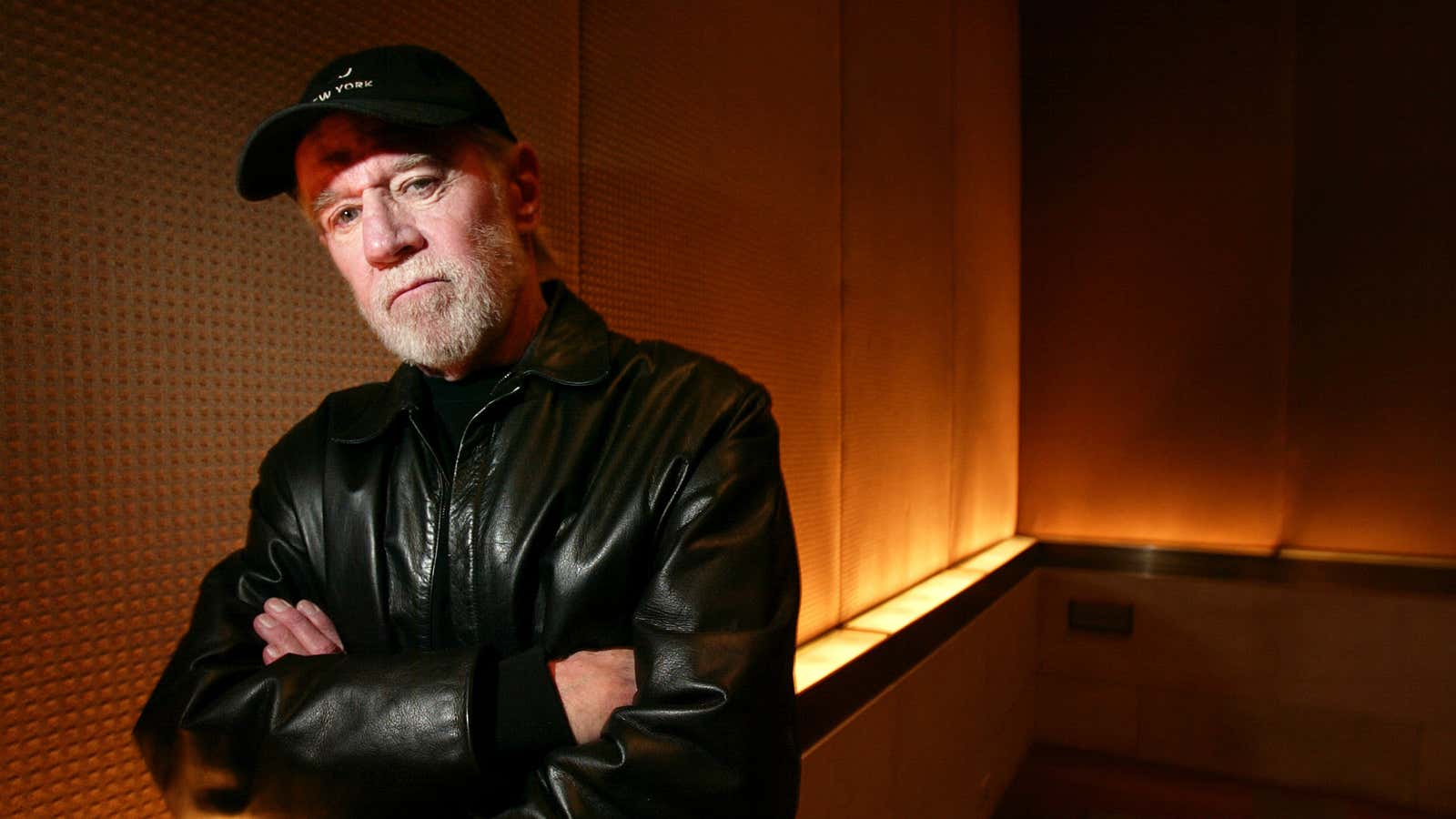

George Carlin and Jackie Gleason, 1969

After the late comedian George Carlin appeared on the Jackie Gleason Show in 1969, an outraged Florida viewer wrote to protest a joke the comedian made about the FBI, which went: “I’m J. Edgar Noover. I have just come back from a stakeout with Ramsey Clark—that is a cookout in the backyard.” (“Noover” was a thinly-veiled reference to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Ramsey Clark served as US attorney general under President Lyndon Johnson. You probably had to be there.)

The viewer, whose name is redacted in declassified documents, called Carlin’s sketch a “flagrant display of poor taste and degradation of one of our finest governmental investigative agencies.”

A copy made its way to Hoover, who found time in his schedule to become furious. “What do we know of Carlin?” Hoover scrawled on the letter.

After what must have been an interesting series of phone inquiries, the bureau concluded that no action be taken against the comedian. In its memo, the FBI wrote: “The [Miami] Office advised that from their prior contacts with Jackie Gleason…they are of the opinion that Gleason holds the Director and the FBI in highest esteem and that Gleason himself thinks that the Director is one of the greatest men who has ever lived.” Case closed.

Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In

, 1972

Two years later, several viewers of the sketch comedy show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In wrote to Hoover to complain about a segment making fun of the director. “I believe this was in extremely poor taste and an insidious propaganda effort to undermine the public’s confidence in you and the FBI,” wrote one complainant from Chicago, before signing off “Keep up the good work.”

The letter arrived a month after a break-in at an FBI office in Pennsylvania revealed that Hoover was running a massive domestic surveillance program. Nevertheless, Hoover found time to personally respond to at least four of the Rowan and Martin-related letters. “I…greatly appreciate your defense of the FBI against the inane mockery of this program,” Hoover wrote to one complainant in Seattle.

The Monkees, 1967

A heavily-redacted 1967 file reveals that the FBI also turned its attention to the Monkees, the bowl-cut-bearing stars of the eponymous TV comedy about a boy band. The agency opened a file on the group after a concert where “subliminal messages” against the Vietnam War flashed on a screen behind the band. What became of the Monkees and the FBI? We do not know; the file is almost entirely blacked out.