Until recently, if you bought a new book on Amazon, your default option was to buy that book from Amazon. That’s no longer the case.

On March 1, the e-commerce giant quietly made a change that allows third-party booksellers to become the default option for any new books you’re trying to buy. This is how the rest of the site operates, and it means you’ll see cheaper options for new books right away, without having to dig around in the already very crowded UX of Amazon’s product pages.

But many third-party booksellers have a sketchy reputation in the publishing industry, and the change has American authors and publishers nervous that Amazon, having already chomped away at their profits, is trying to lick up a few more crumbs from the pie.

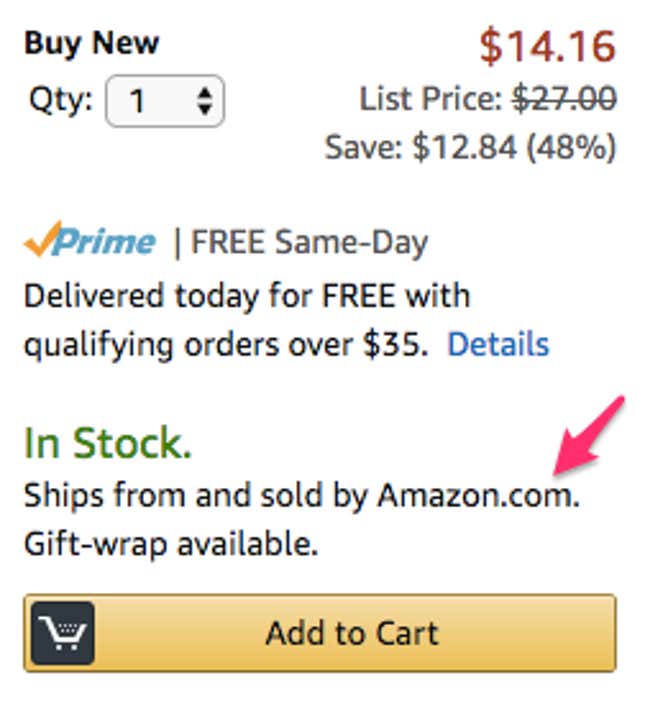

Here’s how it works. When you search for a book on Amazon, you’ll see a box on the right-hand side like this (not including the pink arrow, which I’ve added), called the Buy Box:

This book, Elif Batuman’s The Idiot, defaults to “sold by Amazon.com,” which is standard for a new or relatively popular book.

But if you’re looking for a new copy of an older title, such as Born Confused, a 2002 YA book by Tanuja Desai Hidier (I loved it as a teenager), Amazon might first offer you a cheaper version sold by someone else. Even though Amazon carries new copies, the site determines that the third-party seller, after passing some eligibility standards, is a better deal for customers (read: cheaper).

To authors and publishers, Amazon mainly functions as a book distributor and retailer. It orders books from publishers directly, stores them, and ships them to the people who’ve bought them from the site. Amazon gets a cut of the revenue, and so does the publisher, and so does the author of the book.

But with Amazon acting more like an algorithmic message board, letting sometimes shady third-party sellers get in front of click-happy buyers, publishers and authors risk getting nothing. The tweak to Amazon’s site means that the used-book business, a decades-old thorn in the side of the publishing industry, now has even lower barriers for reaching potential customers. But is there any sense in fighting this?

“The outcry is a little silly,” says publishing consultant Jane Friedman. “You can’t fight the used-book market just like you don’t want to fight the library market.” What publishers should be legitimately worried about, she says, is where the third-party sellers get their books, which is largely a mystery. Though Amazon says only new books qualify to compete for the “buy box,” authors are worried that third-party sellers are trying to pass off gently worn books as new.

In an emailed statement, Amazon emphasizes that the books section of the site now just operates like the rest of it. (Though at the time of this writing, Amazon still lists books as an exception to its usual Buy Box guidelines.)

Industry squabbles aside, a book is a book. Plenty of customers are happy with mildly worn copies or don’t care about the legitimacy of the provenance of their books, so long as the story is the same.