Deloitte has what it calls an “apprenticeship model.” The international auditing and professional services firm hires thousands of entry level employees with the expectation that most of them will work hard, then leave after they’ve learned marketable skills. The organization—like many companies—looks like a pyramid, with many more employees at the bottom level than at the middle or top level.

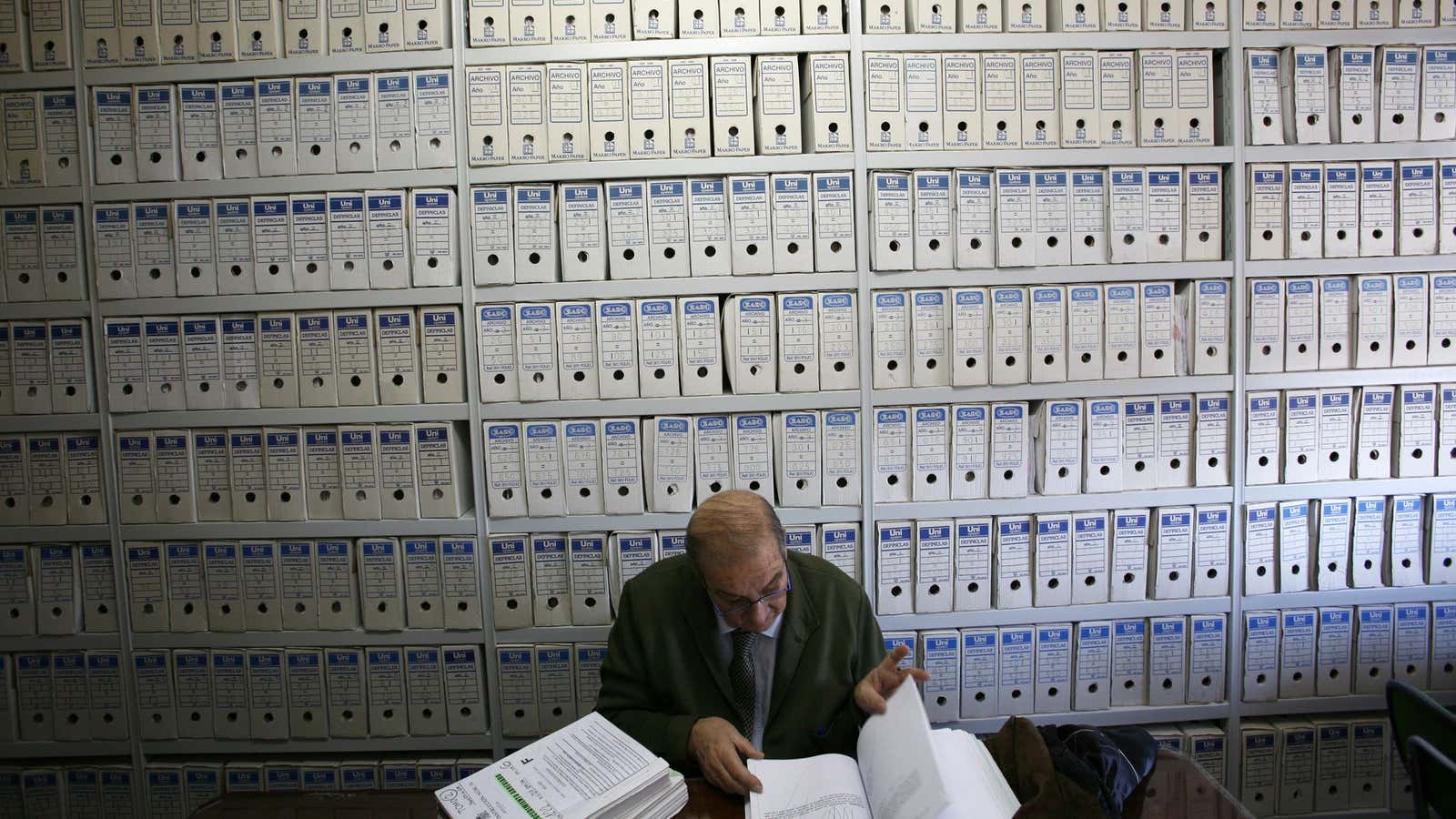

That structure makes sense when there’s a lot of grunt work to do. In the process of auditing a company, for instance, Deloitte employees used to pick up to 100 contracts to review manually. It was a cumbersome process, says Cathy Engelbert, CEO of the professional services firm: “It would take weeks, and it would be subject to human error.”

Today, Deloitte has technology capable of scanning and reviewing thousands of contracts–an entire year of human work–in an hour.

As Deloitte relies more on AI, it won’t necessarily have the same need for entry-level employees to do basic work such as combing through contracts. Increasingly, the organization will look more like a diamond: It will still need human workers to review the machines’ output and make decisions AI can’t, but the greater need will be for the middle-level employees who have the experience to make judgment calls.

Here’s the problem, Engelbert says: “Where do [those middle-level employees] get that experience and judgment? That’s probably the number one thing I worry about as we shift our model.”

Deloitte has been rolling out its machine learning technology, which it calls “Argus” in its audit business and “D-ICE” in its consulting business, since 2015. Developed in partnership with the contract search technology company Kira Systems, the technology promises to cut down on drudge work across the organization.

Reviewing endless contracts may may be tedious, but it’s also instructive. And without this entry-level experience, Deloitte will have to find new ways to train and develop middle-level employees. Companies across other industries will face a similar problem. In law, for instance, natural language processing can now aid in scanning documents to find those relevant to a legal case, a task that in the past would have been done by a new lawyer, learning the ropes.

A common answer to the fear that artificial intelligence will take over jobs is that machines are most likely to take over the types of tedious, repetitive tasks that humans find boring. Humans don’t want to do these jobs, the argument goes, so this isn’t a great loss. Their skills and humanness are better applied elsewhere.

But that misses an essential point that anyone who has worked their way up in a career knows: All that grunt work is actually instructive for workers. And without any experience in the trenches to draw upon, that training will be hard to replicate.