In a recent article in Quartz, Gwynn Guilford made the crucial point that the turbulence in China’s financial system is a debt crisis, not a liquidity crisis. She explains:

What it means is that China’s massive stimulus from 2009 to 2011 sunk money into projects that are generating little or no returns. The continuing gush of credit allowed companies to paper over these losses by covering their bad debts with new loans…But whatever the size [of China’s indebtedness], it’s now big enough that the system needs colossal amounts of liquidity even to keep above water.

This paragraph explains not just the reality of China’s economic problems but also that of the United States, Europe, Japan and most other countries in the world. The problem is that resources have been misallocated as a result of the orgy of monetary creation that the central banks of the world enjoyed during the last several years—mind you, not just after 2008, but for at least a decade and a half before.

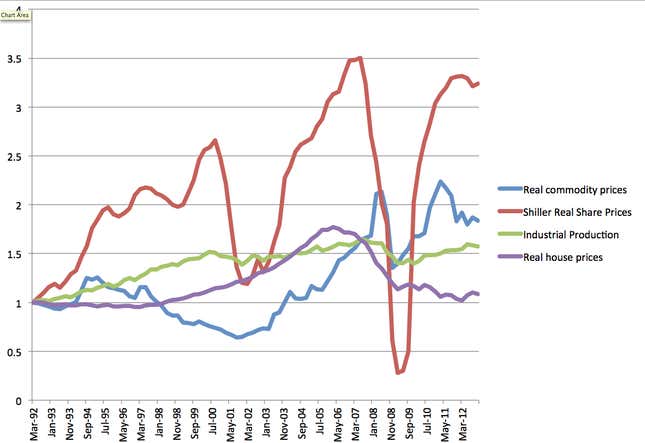

By doing this, they pushed money into activities that were profitable only under the artificial conditions created by unsustainably low interest rates and excessive levels of liquidity in the banking system. This was the case in China, where the huge amounts of liquidity created by the People’s Bank of China in the aftermath of the 2008 global crisis found their way into (surprise, surprise!) capital market speculation and enormous real estate projects that can be accurately described as white elephants. This was exactly what had happened in the US when, as shown in the graph below, Alan Greenspan caused the massive dot-com boom and bust, and then, to get out of it, the even more massive booms and busts of the housing markets, stock markets and commodity prices that all collapsed in 2008. Then, Ben Bernanke did the same, creating a third stock market boom and a second commodities boom, which at this moment is in danger of exploding into an unprecedented collapse.

The same happened in Europe, where the huge liquidity created by the European Central Bank went to finance the unsustainable deficits of the PIIGS (the countries in the periphery of Europe, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain). The same happened in Japan, with real estate loans in the late 1980s.

In each of these episodes in the US, Japan, Europe and China, enormous losses were discovered, but most of them were papered over by issuing more liquidity.

But, what does it mean to paper it over?

Financial intermediation has two sides. On the one side, financial institutions borrow money and on the other they lend it. The problem arises when they lend to unsustainable activities that cannot repay their obligations. When, for whatever reason, increasing numbers of borrowers become unable to service their debts, the banks become illiquid—that is, short of cash because they have to pay their own obligations and the loans in which they have invested them are not producing. When banks become illiquid, they fail. In these circumstances, central banks create liquidity (that is, money) and give it to the banks to prevent their failure. The banks pay their obligations with the currency they get from the central bank, not from the cash generated by their loans, which is insufficient because the loans have turned bad.

This appears to be a wonderful solution because it seems painless. Who cares if the banks are insolvent if they are liquid and can keep on operating with central bank money? The problem is that, to keep on going, banks have to lend the money to the bad borrowers—those who cannot repay their debts—because these are the ones that could bring them to bankruptcy. Take the example of Greece. The country cannot repay its debts. If it defaults, most German and French banks would fail. Thus, the banks pretended that Greece would repay, and kept on providing loans (liquidity) to it, so that it could service their already bad loans because if they failed to do so, the banks themselves would go bankrupt. The snag is that refinancing an insolvent borrower is like throwing cash in a bottomless pit. To pretend that Greece stays current with its obligations, you have to give it the money it needs to service the current debt, plus the interests, plus additional financing to cover its fiscal deficit (that is, Greece keeps on spending more than it receives, and you have to finance this difference to pretend that it is solvent). Of course, this is throwing good money after bad, but for the sake of protecting the banks all central banks have done it. Since the loss makers that receive such attention from the banks are like bottomless pits, the debts skyrocket and grow like snowballs, turning worse every day.

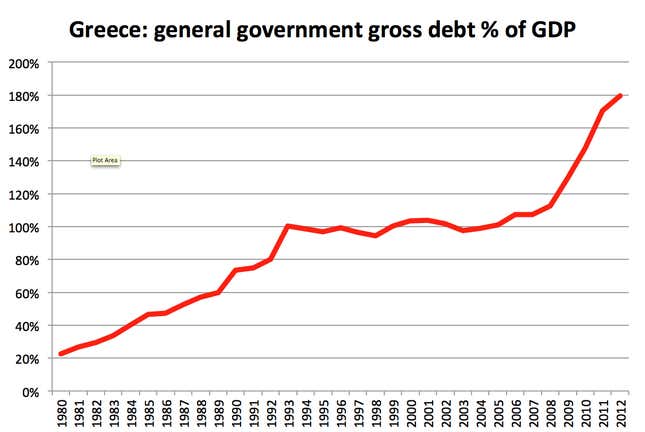

If you want to see how this works, look at the next graph. Note that the Greek crisis exploded in 2008, when it became clear that Greece could not repay its debts. At the time, the debt was equivalent to 100% of GDP. Now notice that after that, as a result of the high-sounding rescue programs, the debt of Greece has increased to become 180% of GDP. In fact, the really impressive escalation of debt has taken place since the rescuers (the IMF, the European Commission and the European Central Bank) began to help Greece to reduce it. Do you think it is easier to repay 180% of GDP than 100% of GDP? Do you think that the rescuers have really been trying to help Greece?

In fact, they have been helping their bankers to survive one more day even if they are bankrupt. However, in the meantime, the problem has become worse, because the amount that can be recovered from Greece is smaller by the day. By keeping the insolvent banks liquid, the central banks are helping them to become even more insolvent in a game in which the banks are expecting that eventually the government will have to absorb all their losses through other means (that is, not lending them liquidity but giving the cash away to them).

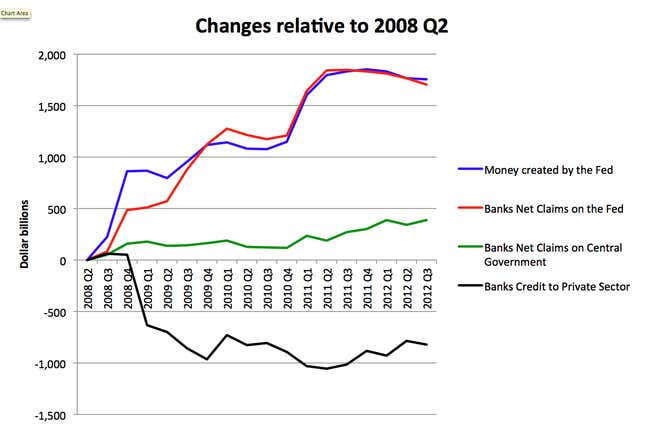

The Federal Reserve has been doing that by purchasing $85 billion monthly in securities mostly owned by the banks, many of which could be of doubtful recovery (you cannot check the quality of the securities when buying such incredibly large amounts). The banks receiving the cash in exchange for these doubtful securities are not lending it to the private sector. As shown in the next graph, they are depositing it back in the Federal Reserve (banks net claims on the Fed) in what seems to be a purposeless exercise: The Fed creates money and gives it to the banks, and the banks deposit the money back at the Fed. The Fed insists that there is a purpose—that is, encouraging credit—but credit to the private sector remains $820 billion lower than in 2008, even if the money created by the Fed is $1.7 trillion higher. What could be the purpose of this? The banks are exchanging doubtful securities for good cash deposited at the Fed. That is not liquidity creation, it is a transfer of wealth.

Thus, we can summarize the results of the orgy of monetary creation that has overtaken the central banks of the world in three categories.

First, it helped zombie banks to keep on operating while they were bankrupt. In the process, the debt problems have snowballed as the logical result of throwing bad money after good money.

Second, more than helping to keep credit to the private sector flowing, the enormous Quantitative Easing monetary creation programs of the Fed may be solving the problems of the bankers, which, though they currently have insolvent banks, may emerge from the crisis having good banks.

Third, the credit that has trickled down to the private sector has produced a series of bubbles, some of which have already exploded. Some others are about to explode. The bubbles are extremely damaging because they direct resources toward activities that are bound to fail when normal conditions return. This is absolute waste.

There is no better example of such waste than the ghost cities built in China with the enormous amounts of money created by the People’s Bank of China in the wake of the 2008 crisis. The People’s Bank did that in the spirit of Nobel laureate Paul Krugman, who promotes monetary creation as the cure of all ailments. Krugman went to such extremes as to say, in a Fareed Zakaria GPS Sunday program, that preparing the defense against a potential space alien invasion would end the slump in 18 months, just because the spending would excite the economy. We don’t have to imagine a potential invasion of Martians to see what would be the result of Krugman’s recommendations. We can just go to China and see the ghost cities built with the two or three trillion dollars of money created by the People’s Bank of China. They are large and pretty but, as shown in a recent 60 Minutes report, nobody lives there. They have become costly monuments to the horrendous waste that unbridled monetary creation generates.

In attention to the inspiration that Krugman has given to these kind of monuments (some of them alive, like Greece, some of them made of cement and steel), the Chinese government should baptize these giant white elephant “Krugman cities,” so that future generations do not forget what is the cost of printing money in Krugman’s style.