The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on Tuesday dropped this enormous study on the economics of education around the world. Seriously, it’s 440 pages of data tables, charts, and graphics taking a look at the educational trends of the industrialized world. Want to know the proportion of Greece’s population over the age of 55 with at least a secondary education? It’s in there.

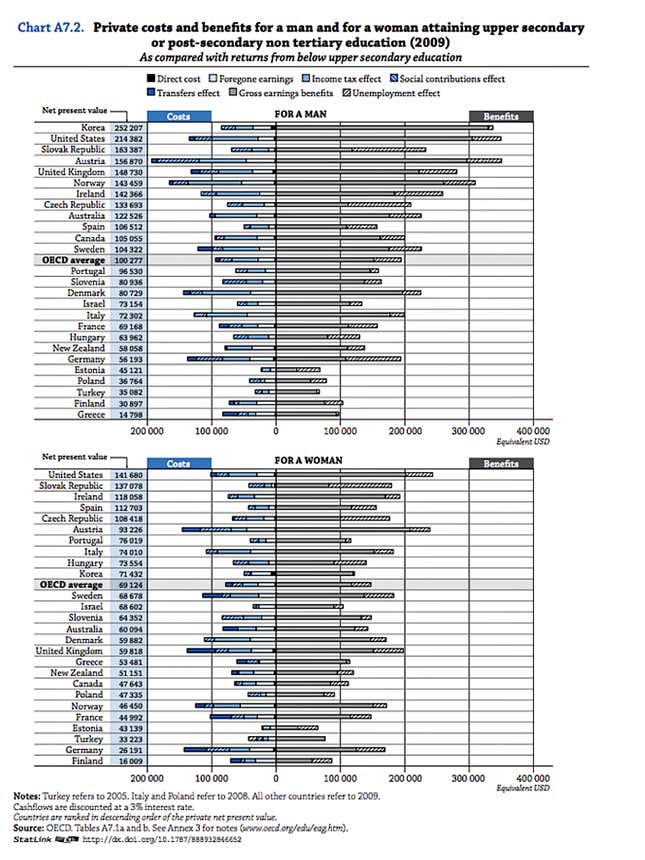

We didn’t read through the whole report. But on a skim, the following chart stood out. It shows, very clearly, the difference in economic outcomes for men and women obtaining the same level of education. As seen in the chart, the term “upper secondary or post-secondary non tertiary education” applies to a person with a high school diploma or with vocational training, ready to enter the workforce. What’s clear is that men with this level of education make a lot more money. (Men in Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Spain being an exception.)

On average across OECD countries, a woman can expect a net gain of [$]69,000 over her working life—about [$]30,000 less than a man. The gender gap in private net returns is particularly pronounced in Austria, Korea, Norway, the United Kingdom and the United States. The difference is largest in Korea, where gross earnings benefits for a man attaining an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education are around [$]250,000, but only [$]71,000 for a woman. The main reasons for this difference lie in differences in social transfers and unemployment costs between the two genders.

The same holds true of men and women holding college degrees. “Tertiary-educated women aged 55-64 can expect to earn 72 percent of what men of a similar age and education level earn,” the report states. Granted, education still is a great investment for women. It’s just that it is still a better one for men.

Brian Resnick is an online editor at the National Journal.

This originally appeared at the National Journal. More from our sister site:

Obama’s climate speech reflect Washington’s gap

If Snowden wasn’t a spy before he went to Russia, he may be now