Rarely does history give us such a compelling juxtaposition—both in time and in character—as what happened one hundred years ago this Spring.

On Apr. 2, 1917, president Woodrow Wilson delivered his “War Message” to Congress outlining the rationale for the US to enter World War I. Just four days later, Congress overwhelmingly declared war upon the Imperial German government. The entry of US forces in the late stages of World War I would prove decisive in the Allied victory more than a year later. Three days after Congress’ declaration, an equally powerful force was boarding a sealed train in Zurich, Switzerland. Vladimir Lenin, who had been in exile in that country for a decade, had struck a deal with the German authorities to gain secret passage for himself and 32 of his comrades to Russia. The Germans had calculated that allowing Lenin to return to Russia would destabilize the current Provisional Government and knock Russia out of the war. They were right. A mere seven months after that train arrived at Finland Station in Petrograd on Apr. 16, Lenin sat at the helm of a new Russia.

Simultaneously, Wilson and Lenin set into motion a series of events that would ultimately define the 20th century geopolitical order. The historical narrative often focuses on their differing personalities and methods. Wilson, the bespectacled former academic and idealist, sought to promote a more transparent and democratic mode of conducting international affairs. Lenin, the firebrand outsider with a hurricane-force personality, sought to foment revolution across Europe to return power to the proletariat class.

But they both shared a common belief that the world order at the time—colonial and hierarchical—was decaying and had to be replaced. It had failed the very people it was meant to serve, plunging Europe into a senseless, destructive war in which millions of lives were lost for a cause that neither the Allies nor Central Powers could articulate.

Once again, a century later, drumbeats of war are sounding and revolution is in the air. America has a very different sort of president—someone who is actively rather than reluctantly threatening the use of military force. Meanwhile, the socioeconomic inequities Lenin railed against have become a global epidemic. The combination of geopolitical risks and domestic upheavals appears set to plunge the world into a reprisal of the military and trade wars that substantially derailed globalization for the entire inter-war period of the 1920s and 30s.

Will it happen? Is the world really as prone to systemic destabilization as it was then? Is the next disaster around the corner?

Given the far higher degree of interdependence among economies than existed a century ago—spanning not only trade but also currency and debt markets, cross-border fixed investment and portfolio capital flows, and deep supply-chain integration—the logic can cut both ways. On the one hand, instability in one corner of the geopolitical or economic system can quickly ricochet around the world. On the other hand, collective resources can be marshaled to isolate risks and strengthen systemic foundations.

Examining the global landscape of the quarter century since the collapse of the Soviet Union and end of the Cold War world yields interesting conclusions about our collective ability to manage unpredicted events and risks.

Recall that the post-Cold War period was a short-lived honeymoon. In Aug. 1990, Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Kuwait and sent oil prices skyrocketing. The early 1990s civil war in the Congo witnessed five million deaths, the highest toll since World War II. At the same time, Yugoslavia’s disintegration rapidly accelerated, unleashing a genocidal civil war that claimed nearly 150,000 lives. NATO found a new purpose and mission in the Balkans, soon to expand to Central Asia as 9/11 became the current generation’s most salient flashpoint.

The rest isn’t even history yet, as the long shadow of 9/11 continues to loom large. The US invasion and occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan persist in form if not with the same troop levels, while the broader Middle East is engulfed in the meltdown triggered by the 2011 Arab Spring. An estimated half million Syrians have perished in the country’s civil war since 2011; the jihad terrorist diaspora made 2014-2015 the bloodiest years Western Europe has experienced in decades.

Sociopolitical upheavals have hardly been confined to the Arab world, with the 2008 financial crisis unleashing crippling economic austerity and financial repression across the West, while Occupy Wall Street and populist political movements gained steam culminating in the past year of Brexit and Trump. Furthermore, from the Taiwan Straits and North Korea to Iran’s nuclear program and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, great powers perpetually find themselves on the brink of significant escalation. In 2014, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe toured the world, directly analogizing China to imperial Germany and warning of history repeating itself.

And yet, here we are: No nuclear war with Russia or North Korea, but a surprisingly synchronized global economic recovery. Brexit didn’t bring down global markets; on the contrary, UK growth forecasts are being upgraded and several European stock markets are at multi-month highs. Trump has backed down from his trade war threats. Energy prices are at structural lows. Greece, Italy, and Spain are still in the Eurozone.

If every downside event that occurs is viewed with the “recency bias” that inflates its significance due to its proximity in time, then we would live in constant fear and paralysis. Planning for the future would be pointless. The robustness of globalization that we take for granted would instead be a chimera.

In fact, much of what we refer to as volatility is actually just turbulence. To use a volcanic metaphor, tremors (turbulence) happen all the time, but they do not all result in genuine earthquakes (volatility). In fact, very few tremors become even noticeable earthquakes at all. The complex geological structure of the Earth absorbs and dissipates their energy across the planet’s mantle, muting their impact.

Globalization itself performs a similar function—it is the planetary network that absorbs and dissipates shocks. Unfortunately, globalization today is far too often spoken of as a phenomenon controlled by a light switch, turned either on or off by conflict or protectionism. But much as analogies to the pre-World War I era are of limited utility, so too have been recent proclamations of the “end of globalization” due to 9/11, the failure of the Doha trade round, the financial crisis, nearshoring, industrial policy, and border adjustment taxes. Take your pick; all such claims look shallow as global growth recovers, trade growth expands (especially in services), and capital seeks yield in high-growth markets.

The chasm between the media amplification of noise over the meaningful signals has perhaps never been greater. Whereas every geopolitical event is presumed to cause a market crash, oil price hike, or name-your-calamity, the reality is that stabilizing forces abound such as monetary stimulus, trade reciprocity, and regional integration.

There is a dangerous tendency to view downside events as structural and upside as merely cyclical. But the reality is more one of action and reaction as energies reverberate to correct excesses. European publics swing populist, yet France has decisively elected a pro-EU president who will work with Germany to restore the Union’s strength. Saber-rattling over the Korean peninsula reached fever pitch, but South Koreans just elected a dovish president whose top priority is de-escalation and peaceful reunification.

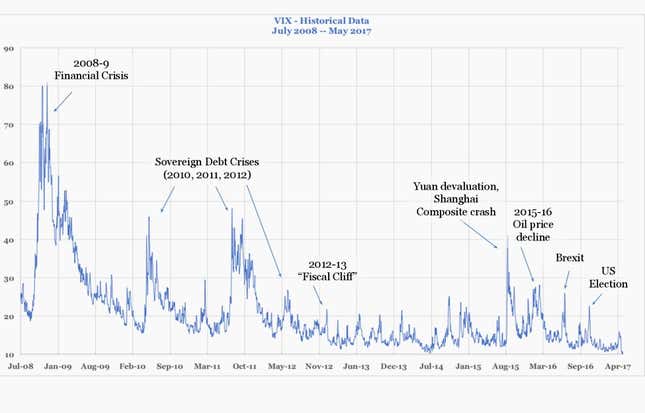

The financial markets have taken note of this dynamic, even if it remains unspoken. The bull market run that began in 2009 celebrated its eighth year in early March. While the enormous equity price gains have been the story du jour, another salient trend has not gone unnoticed: low volatility. The most cited measure of market volatility is the CBOE Volatility Index, or VIX. Technically it measures the implied volatility of S&P 500 index options; practically speaking it rises when markets fall and tends to spike sharply during large market downturns. Hence its nickname: the “fear gauge.”

Figure 1 (below) shows this fear gauge since the 2008 financial crisis, when it hit its peak of 80. As that traumatic event recedes into memory, spikes in the VIX have generally been less frequent, lower magnitude, and shorter duration. Since mid-2012, the VIX has spent most of its time below 20, a level generally associated with market complacency. Many have attributed the stock gains and low volatility to the Federal Reserve’s historically accommodative monetary policies, which has pushed fixed-income yields to such low levels that investors had no choice but to chase returns in stocks.

But this explanation does not fully account for why spikes in volatility are short-lived. Investors have come to realize that the collateral damage due to geopolitical tensions or local elections on companies’ earnings will be minimal. Global banks are much better capitalized than before the crisis and have to provide far greater transparency into their viability and risky assets. Albeit imperfectly, the Federal Reserve and other central banks continue to coordinate and “do whatever it takes” (in ECB chief Mario Draghi’s words) to keep economies moving. This combination has proved to be a very effective stability mechanism. Bouts of market panic and VIX spikes have dissipated quickly; the much feared post-Brexit market decline lasted a few days in the US. No wonder shorting volatility has been an enormously profitable trade for the past five years.

So why does it seem like the world is so volatile? That the next calamity is just around the corner?

Perhaps one answer lies in the very forces that were unleashed a century ago. Woodrow Wilson and Vladimir Lenin stepped into the moral vacuum of the “Great War” and infused a sense of purpose that no other global leader could or dared to. Wilson’s “War Message” was not just a tactical call-to-arms, but an eloquent plea for a new world order founded on democratic principles: “A steadfast concert for peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations….” Similarly, Lenin, shortly after arriving in Petrograd, exhorted the assembled crowd to join him to overturn the oppression and deception: “We must fight for the social revolution, fight to the end, till the complete victory of the Proletariat.” A modern-day Wilson would have rallied the world behind the Paris climate agreement; Lenin would have held court at Occupy Wall Street. Wilson would have taken the bully pulpit to CNBC arguing for central bank coordination while Lenin would be a sought-after counselor to rebellious upstart political parties such as Italy’s Five-Star Movement.

Both Wilson and Lenin exuded the confidence of leaders who inspire followers, which is what makes them so unlike any public officials in power today. Indeed, the lack of any figures with the persuasiveness and stature of these two giants of the 20th century gives the impression that there is no captain to steer the ship—or, more cynically, most of the elected captains are uninspiring, incompetent, or both. This certainly contributes to the sense that grand agendas will fail, or worse, be condemned to mediocre execution and dysfunction.

Unfortunately, there is no end in sight to the vacuum in global leadership. America’s role in upholding the world’s financial, military, and technological order is fundamental but being handled haphazardly. The justifications are given in tweets. The EU is without question the most successful multilateral body in history, yet no single European head of state can articulate a compelling and forward-looking defense of it. Financial institutions provide essential liquidity for sovereigns and corporations, but are viewed with rank suspicion. No wonder trust in formal and global institutions at an all-time low.

And we should not be so sanguine as to believe that earthquakes of volatility are a thing of the past. Suppressing volatility through coordinated action does not mean there aren’t underlying stress factors such as economic friction, high debt, low productivity, aging populations, rising inequality, and geopolitical games of chicken among nuclear powers. Risks abound—from trade policy stoking inflation to an equity bubble to unwinding financial regulation or a China hard landing. But thus far, these scenarios have not panned out, and need not leap from tremors to earthquakes.

Rather than wait for heroes to emerge, then, perhaps we should be investing more in the stability mechanisms we already have. Indeed, the most salient consequence of globalization is that the need for singular political or economic saviors is greatly diminished. The path to long-term stability is not through centralized solutions to global challenges at all, but to self-organizing approaches led by “coalitions of the willing.”

In practically every country and every region, examples abound of these coalitions emerging confronting significant challenges. Central bank coordination evolved over time and was led by a handful of unelected technocrats, not heads of state. China and its neighbors are committing over $1 trillion to infrastructure projects to smooth their commercial connectivity. Cities are banding together to share emissions-reducing technologies that green their industries, even if their respective federal governments have taken a back-seat on climate change. Lending clubs and credit unions have sprouted worldwide to bridge financing gaps for start-ups and home-owners. Coordination without centralization abounds in a connected world.

Ultimately, the legacy of what Wilson and Lenin set into motion may just be this “new normal” of globalization: Decentralized power in the hands of citizens, cities and countries operating in self-organizing coalitions. When the earth rattles and the seismograph shakes, these networks spring into action to preempt and isolate, surround and contain the shock. Each year we ask if this is another 1914, 1915, 1916, or now 1917. And each year proves not to be. Let us hope that by managing all the tremors, we are better prepared for larger earthquakes—or that we are able to prevent them altogether.