Updated: May 22, 2017 at 4:14pm EST

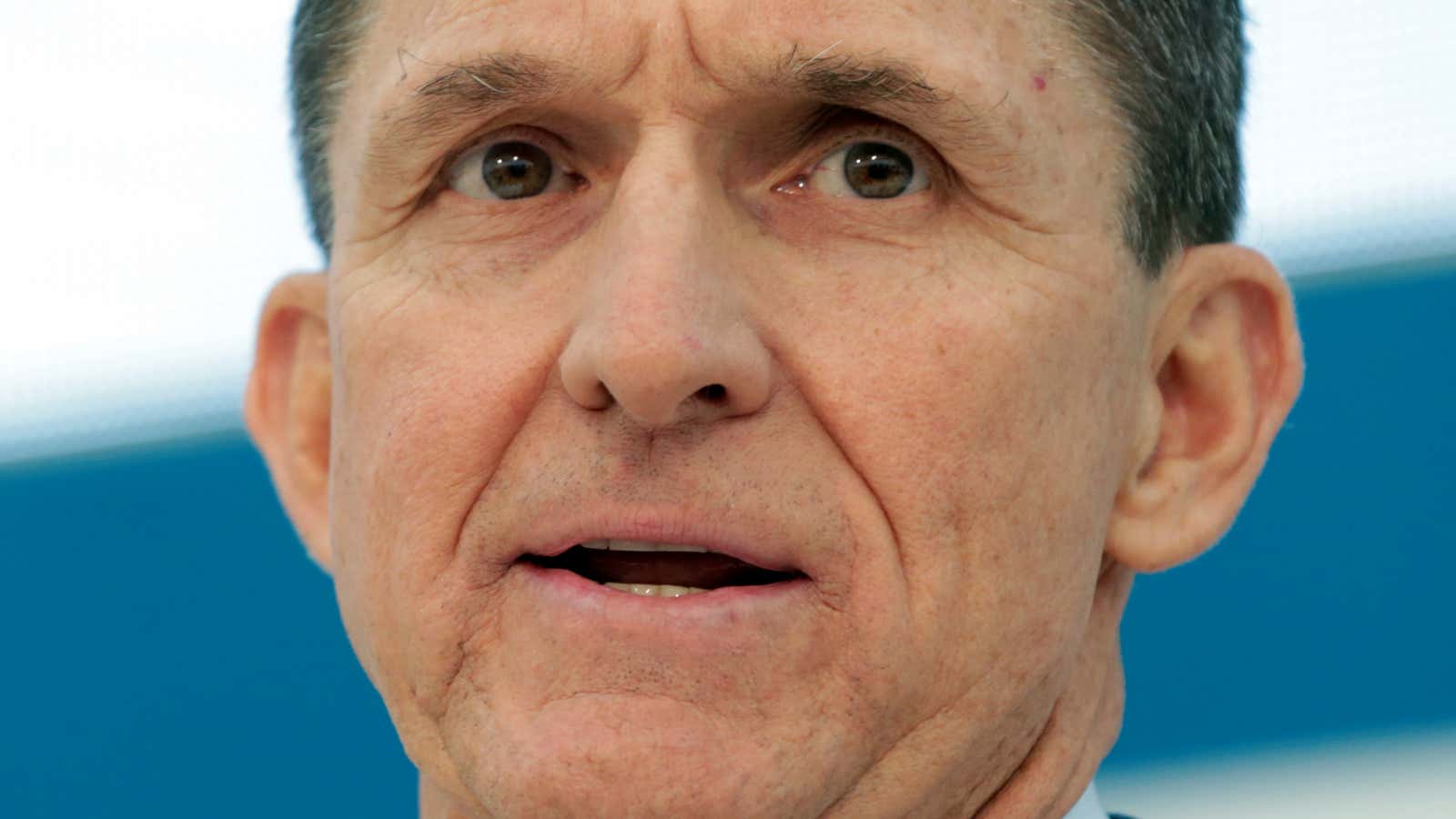

Attorneys for Michael Flynn said today (May 22) that the former US national security advisor will not comply with a congressional subpoena related to the US Senate intelligence committee’s investigation into ties between the Trump campaign and Russia, citing Flynn’s Fifth amendment right to avoid self-incrimination.

“The context in which the committee has called for General Flynn’s testimonial production of documents makes clear that he has more than a reasonable apprehension that any testimony he provides could be used against him,” Flynn’s lawyers said in a letter to the panel.

The decision to reject a congressional committee’s subpoena outright is “not an option that he has legally,” said Josh Chafetz, a professor of law at Cornell Law School and author of Congress’s Constitution: Legislative Authority and the Separation of Powers. ”The whole point of the subpoena power is to force cooperation with people who don’t necessarily want to cooperate,” Chafetz said.

When can a witness refuse to comply with a subpoena?

At its most basic level, a subpoena is a “judicially enforceable” request issued by a government authority. Congressional committees are authorized to issue subpoenas for records or testimony from witnesses.

While it’s not lawful to ignore or issue a blanket refusal to a subpoena, there are legal defenses that can be invoked, including executive privilege or a Fifth Amendment claim, as Flynn has done.

Executive privilege is not formally written into the US constitution. It’s an implied power of the president, upheld by the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Nixon, which maintained the executive branch has limited privilege to avoid subpoena. In practice, this means that certain conversations between a president and his top advisers can be kept from Congress.

Chafetz said the rationale is that within the executive branch, a president must be able to receive candid advice from his closest staff without any of them having to fear being called to testify in full. The courts have found that the executive branch deserves ”some amount of breathing room for internal affairs,” he said.

While defenses like executive privilege or self-incrimination protections can be used in response to specific requests, Chafetz said they cannot be legally used to refuse to testify at all. For example, executive privilege would not apply to anything that occurred before Trump was sworn in as president on Jan. 20, including the campaign and transition, both key time periods in the congressional inquiry.

“If it’s a document subpoena, you might say, ‘Well, this document is privileged, or this document would incriminate me,'” Chafetz said. “But in the context of a subpoena to come testify—especially about things that happened before Trump got into the White House—it’s impossible to imagine that either self-incrimination or executive privilege would cover everything they wanted to talk about.”

What recourse does Congress have if someone refuses to comply?

Congress has the authority to hold in contempt anyone whose conduct or action “obstructs the proceedings of Congress or, more usually, an inquiry by a committee of Congress,” according to Cornell Law. Contempt is a misdemeanor, which can result in 12 months in prison as well as a fine of $1,000.

If Flynn were to ultimately refuse the subpoena, the committee could vote to hold him in contempt. That resolution would then be put to a vote by the full senate. Then, the matter would be referred to the Department of Justice (DOJ), a process that “works really well when the White House isn’t trying to protect the person being held in contempt,” Chafetz said.

However, the Department of Justice does not often follow what Congress wants. In 2008, the House voted to hold White House Chief of Staff Josh Bolten and former White House counsel Harriet Miers in contempt over their refusal to cooperate with an investigation into the mass firings of US attorneys by the administration of George W. Bush. Former Attorney General Eric Holder, Barack Obama’s appointee, was also held in contempt of Congress in 2012 after refusing to turn over documents related to the “Fast and Furious” scandal. In each of these instances, the DOJ declined to prosecute.

If the DOJ will not cooperate and Congress wants to exert more pressure on the White House, there are other options. Congressional leaders could refuse to confirm nominees until Flynn cooperates, or decline to fund programs the Trump administration wants to see carried out.

“The official position that every lawyer will tell you is that invoking the Fifth Amendment doesn’t mean you’re guilty,” Chafetz said. “But from the standpoint of someone who is looking on here, it’s hard to imagine why you would risk infuriating an entire house of Congress by refusing to respond to a lawful subpoena if you’re not trying to hide something.”

This story has been updated.