The US has a new reader-in-chief. Since president Donald Trump doesn’t read much, philanthropist and Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates is now the natural successor to Barack Obama and Oprah.

Last week, Gates recommended a book for college graduates: Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature. It shot to number 2 on Amazon, up from 12,231 the day before, and is still comfortably at number 10 a week later. This summer, Gates has several new recommendations: three memoirs, a big book on humans, and a rare novel. The selected books, narrative-driven and at times emotional, depart from his usually wonky book lists.

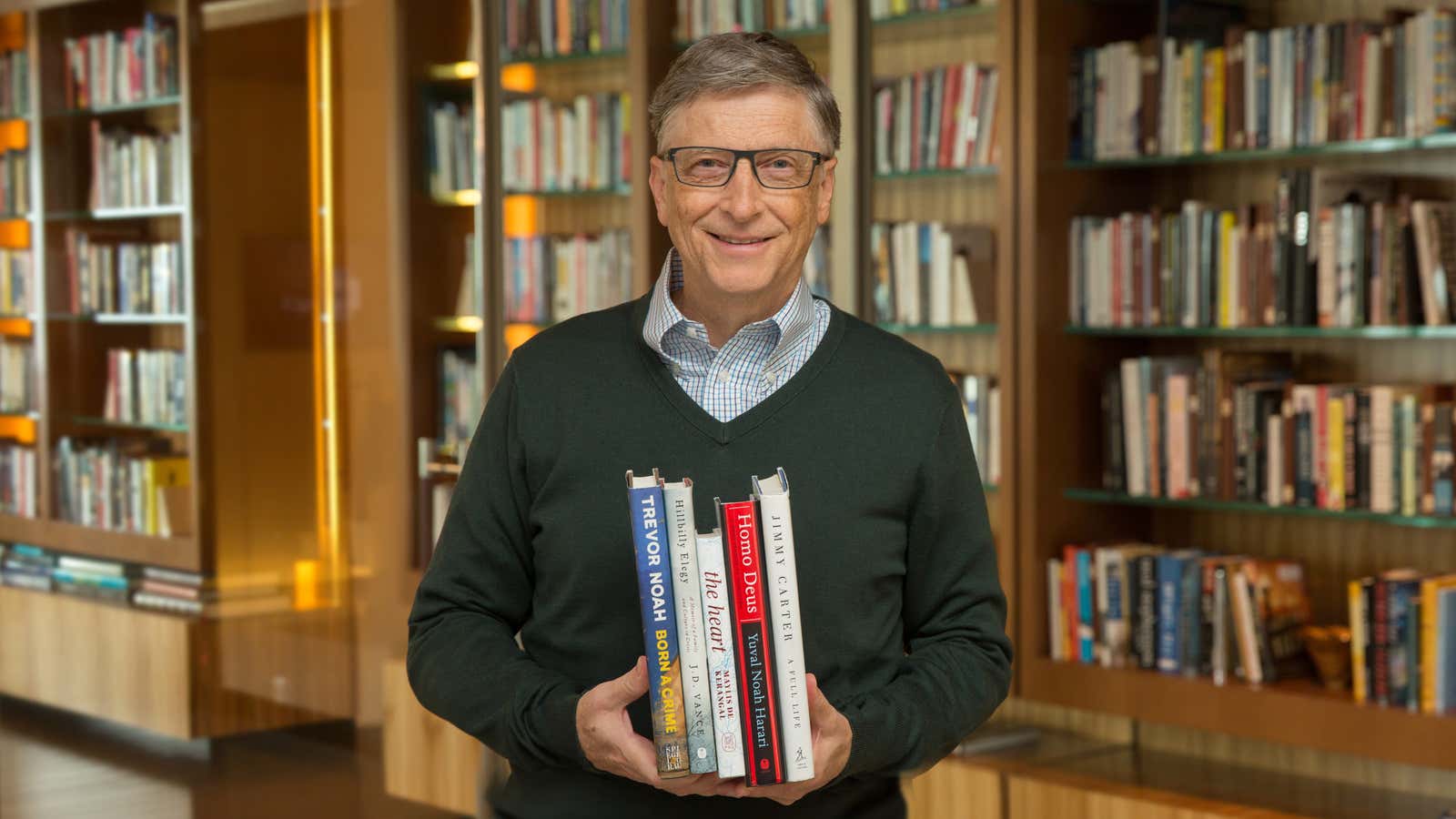

See what Gates picked this year, with some of his notes:

Born a Crime

, by Trevor Noah

Comedian and Daily Show host Trevor Noah recalls his childhood as the product of a criminal act between a white man and a black woman in apartheid South Africa. The book is ultimately an ode to his mother, a fierce and uniquely minded woman.

“As a longtime fan of The Daily Show, I loved reading this memoir about how its host honed his outsider approach to comedy over a lifetime of never quite fitting in,” writes Gates. “Again and again throughout his childhood, [Noah] discovered that language was more powerful than skin color in building connections with other people,” he says.

The Heart

, by Maylis de Kerangal, translated by Sam Taylor

This novel takes place in the 24 hours around an operation, a heart transplant between a teenager killed in a car and a dying woman. Originally written in French, the book follows the lives of the family members, doctors, and nurses involved.

“What de Kerangal has done here in this exploration of grief is closer to poetry than anything else,” writes Gates. He adds that he is drawn to the language of the book: “It makes me think of Vladimir Nabokov more than anybody else. The sentences are rich and full, and they go on and on, which is the exact opposite of how I write. There are sentences that last entire paragraphs. … I went to the dictionary a dozen times to look up words I didn’t know.”

Hillbilly Elegy

, by J.D. Vance

The surprise US literary hit of 2016 was the Hillbilly Elegy, a memoir about growing up poor and white in the Rust Belt and ending up at an elite east-coast law school.

“While the book offers insights into some of the complex cultural and family issues behind poverty, the real magic lies in the story itself and Vance’s bravery in telling it,” says Gates. “Even though Hillbilly Elegy doesn’t use a lot of data,” he writes, “I came away with new insights into the multifaceted cultural and family dynamics that contribute to poverty.”

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

, by Yuval Noah Harari

The author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, which Gates recommended last summer, has a new book that explores what’s next for humans now that they’ve radically altered the rules of life on Earth.

“[Harari] argues that humanity’s progress toward bliss, immortality, and divinity is bound to be unequal—some people will leap ahead, while many more are left behind,” says Gates, conceding, “I agree that, as innovation accelerates, it doesn’t automatically benefit everyone.” But Gates disagrees with Harari on a crucial point, he writes. Gates believes inequity is not inevitable, and those with resources can help to close the gap.

A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety

, by Jimmy Carter

The former US president and prolific author looks back on his life at the age of 90. He writes about his family life, his regrets, and decisions that profoundly shaped his trajectory. Gates read Carter’s book in preparation for meeting with him and his wife, Rosalynn, and says, “The book will help you understand how growing up in rural Georgia in a house without running water, electricity, or insulation shaped – for better and for worse – [Carter’s] time in the White House.”

He adds, “Although most of the stories come from previous decades, A Full Life feels timely in an era when the public’s confidence in national political figures and institutions is low.”