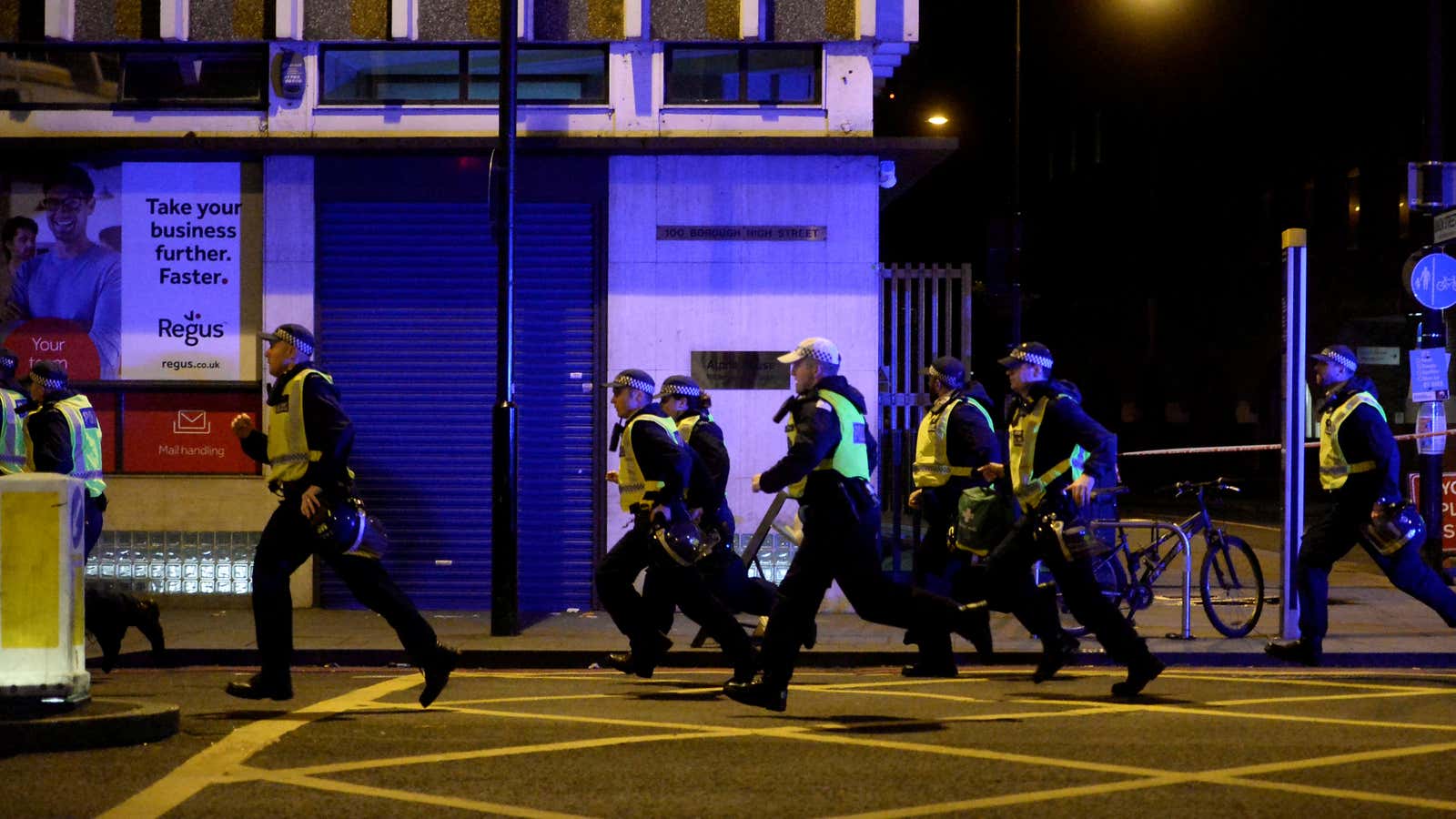

The UK has been hit with its third deadly terrorist attack in as many months. Seven people were killed and almost 50 were injured last night after attackers ran over pedestrians with a van near London Bridge and then stabbed several others in nearby Borough Market. The police shot the three suspects.

The attack was reminiscent of another in Stockholm in April, when a man drove a truck drove into a department store in the city center, and another attack in London in March, when a man ran down pedestrians on Westminster Bridge in London and stabbed a police officer afterwards.

These attacks are stark reminder of a disturbing trend: As terror attacks become less sophisticated, they are also becoming more difficult to prevent. Quartz considered the implications of this after the previous London and Stockholm attacks; the text is reproduced below.

Vehicle ramming attacks are devastatingly simple. Attackers don’t need bombs or much training—just a vehicle, basic driving skills, and the will to plow into a crowd. These kinds of attacks have escalated since the 2016 Nice attack, when a man drove a truck through a large crowd in the southern French city, killing more than 80 people.

The Islamic State (ISIL) took responsibility for the attack, and has since promoted the concept of vehicle attacks. In the November 2016 issue of the group’s Rumiyah magazine (pdf), ISIL said: “Though being an essential part of modern life, very few actually comprehend the deadly and destructive capability of the motor vehicle and its capacity of reaping large numbers of casualties if used in a premeditated manner.” The article contained an image of a rental truck and the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York.

Vehicle attacks have risen accordingly. There have been nearly as many vehicle ramming incidents in the past three years (including those targeting the public, police, and military) as there were in the preceding decade, according to Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

Most of these resulted in a handful of casualties at most, but the Nice attack marked a turning point by lowering the bar for would-be terrorists and sending the message that “you don’t have to become a bomb maker to successfully execute a mass casualty attack,” Stanford terrorism expert and former US Special Forces Colonel Joe Felter noted in July 2016.

The Nice attack was quickly followed by the tragedy at Ohio State University, when a refugee lawfully residing in the US drove a vehicle into a group of students on campus, and then attacked them with a butcher’s knife. In December 2016, an attacker drove a truck into a busy Christmas market in central Berlin, killing 12 people and injuring around 50 more. ISIL claimed responsibility for both.

Preventing these attacks can be nearly impossible, given the ubiquity of civilian vehicles and public crowds. As Alain Winants, former head of Belgian intelligence, told Newsweek, “You can’t close off an entire city.”

For instance, the concrete bollards long used to fortify urban public targets wouldn’t have been possible in the Berlin market attack; there were 2,500 Christmas markets erected around Germany and 60 in Berlin alone.

So far, the best response officials have mustered is to tackle the root cause. British authorities have turned to schools, doctors, faith-based centers, and charities to divert people from the draw of extremism.