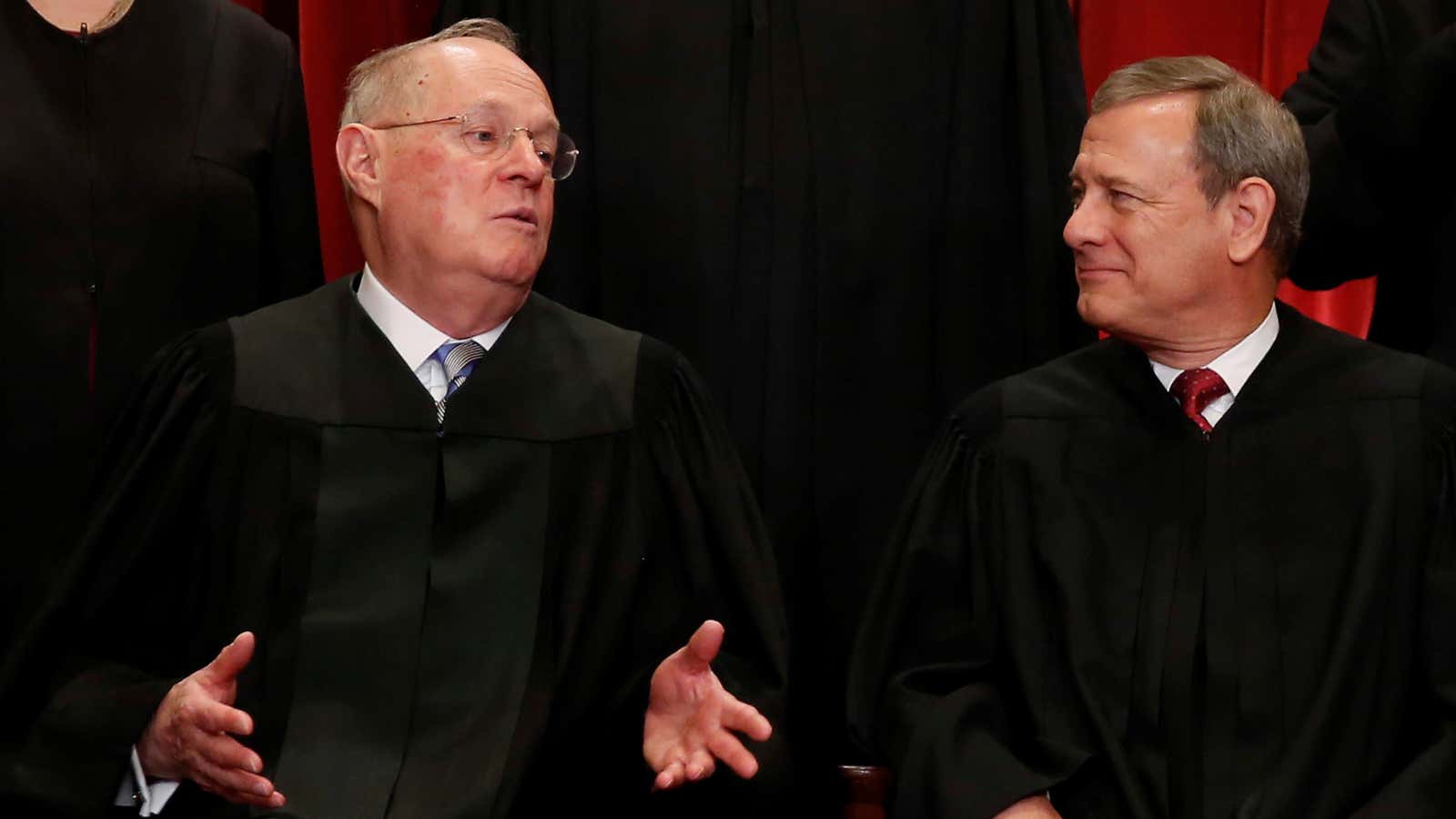

One of the greatest anxieties of liberals in the United States is domination of the country’s Supreme Court by ideological conservatives. Such a rightward swing would put decades of social progress at risk─perhaps most notably, the decision in Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion nationally─and would certainly create more room for president Trump to pursue an uncompromising, hard-right agenda. Several of the nine sitting justices are rumored to be weighing retirement, including 81-year-old Anthony Kennedy, a conservative appointed by Republican president Ronald Reagan who, in recent years, has become an unlikely hero of the American left.

On paper, the court is split five-to-four, conservative to liberal; but Kennedy is generally considered a judicial wildcard. He voted with the conservative-dominated minority against the Affordable Care Act in 2010, but has sided with the majority on legalizing same-sex marriage and upholding abortion rights. For such departures with conservative social doctrine, he has been lauded for a non-partisan commitment to rule of law.

Understandably, the prospect of Kennedy leaving the bench terrifies liberal observers of the court. In that event, the president would likely appoint a less yielding conservative, forming an unbreakable right-wing judicial majority, perhaps for decades after his presidency ends. According to Reuters, liberal activists have approached a number of Kennedy’s former clerks and other acquaintances, asking them to urge the justice to stay on─at least through the mid-term elections in 2018. It is then that Democrats have an opportunity to form a majority in the Senate, where constitutional authority to confirm judicial appointments would make it difficult for Trump to appoint a more inexorable conservative.

A test of Kennedy’s resolve may arise in the court’s consideration of the president’s executive order banning entry to the US by citizens of six Muslim-majority countries. The Department of Justice has asked the court to overturn a decision handed down by the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld a freeze on the travel ban, and allow parties to proceed with oral arguments. So-called “emergency application” of the ban in the interim would also overturn a nationwide injunction issued by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in January.

The government requires a five-vote majority for the order to survive. We can expect the four liberals to oppose the ban, and if Kennedy swings left, it will bring a decisive end to months of struggle between the executive and judicial branches on one of Trump’s tent-pole campaign promises.

The possibility boils down to a key bit of legalese, according to Bloomberg’s legal-affairs columnist, Noah Feldman. Lower-court decisions have focused on the existence of “animus,” Feldman explains, or “illegitimate prejudice” in the crafting of the order; and, as it happens, animus is one of Kennedy’s favorite instruments for batting down cases. “If Kennedy reads Trump’s executive order temporarily blocking immigration from six predominantly Muslim countries as an exercise of anti-Muslim animus, the ban will fall at the court,” he writes.

Kennedy first identified animus as a contemporary means to invalidate unconstitutional laws in his 1996 opinion in Romer v. Evans, in which the justice sided with the majority in striking down an amendment to the Colorado state constitution which forbade the state legislature and city governments from adopting anti-discrimination laws to protect LGBT Americans. The amendment’s “sheer breadth” was “so discontinuous with the reasons offered for it that [it] seems inexplicable by anything but animus toward the class that it affects,” he wrote in an opinion that could very well substitute “Muslims” for “gay people.”

Kennedy has applied the animus argument in a number of landmark cases since, including United States v. Windsor, which struck down the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), and Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalize same-sex marriage in all 50 states. In Feldman’s view, it’s not a legacy Kennedy is likely to forego so close to retirement age: “I find it almost impossible to believe that Kennedy, at 80, would want to sign an opinion closing his eyes to animus, which he himself did so much to make into a constitutional touchstone.” The question remains, however, whether Kennedy’s animus towards animus is enough to inspire another four years, at the least, on the court. Because, given the ideological nature of the Trump administration, its a concept that will surely rear its head again.