Kampala

When Patrick graduated last November from nursing school in Soroti, a district in eastern Uganda, he expected the job search to be tough. As many as 58% of Ugandans are said to be out of work, according to 2016 census results, a crisis touching even the educated. With less than 10% of the government’s budget going towards health, many medics are idle, despite the great need for them. “There are so many nurses who want jobs,” says Patrick, who asked for his real name to be changed to protect his privacy.

Nearly six months later, an opportunity arose for him and his jobless peers in the last place they might have imagined.

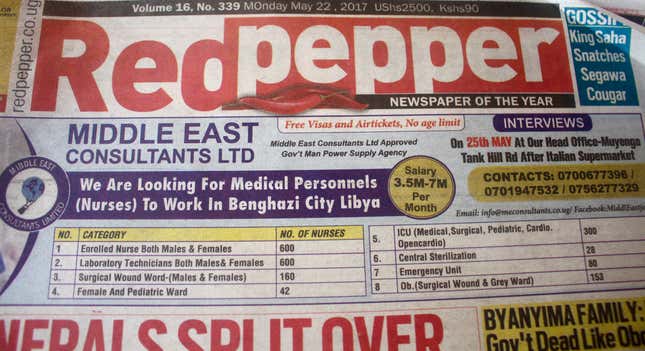

Front page newspaper ads run across Ugandan print media by local recruitment firm Middle East Consultants Limited (MEC) in May called for nearly 2,000 nurses, lab technicians, intensive care unit and emergency staff, among others—in Benghazi, Libya. The ads boasted a pay of up to seven million Ugandan shillings ($1,950) per month, plus “free visas and air tickets, no age limit.” The average pay for a nurse in Uganda is about 400,000 shillings ($100) a month, while a doctor is said to earn about 700,000 shillings ($194), according to 2014 numbers from the health ministry.

The offer appeared to be part of a deal between MEC, which is registered with Uganda’s labor ministry, and the Benghazi Medical Company, based in the crisis-torn north African country. It was hailed by MEC as a great opportunity for Ugandans by MEC, which claims to have “managed to export” over 7,500 Ugandans for work outside the country. But the controversy that followed it is indicative of the deep conflict Uganda is facing over the limited opportunities it has for its pool of qualified medical professionals.

In the past few years, thousands of Ugandans, mainly domestic workers and laborers have sought greener pastures, mainly in the Middle East. Many of them, particularly female maids, have ended up being mistreated and exploited by employers. Health workers have joined this exodus: according to a 2014/2015 report by the Ministry of Health, one third of the country’s 81,000 health workers were unemployed or had emigrated. Botswana and South Africa were the main destinations for those who had left.

In May, MEC said it had been approached by the Benghazi Medical Company about supplying medics for Libya. In a video posted on MEC’s website, the medical company said the deal was a “humanitarian mission,” adding “we give jobs for Ugandan people and we solve some problems (with) human resources in our country.” Libya and Uganda share a history, with the late dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who gifted a mosque to Uganda, still popular in the east African country today. Nearly six years after the fall and death of the despot, Libya remains politically unstable and at the center of a refugee and migrant crisis.

But activists like Moses Mulumba, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Health, Human Rights and Development, a non-profit, want the deal and others like it stopped, for fear of the financial impact of medical brain drain on Uganda, and the likelihood that it will lead to more preventable sickness and death. “Critical (areas) like reduction of maternal mortality will inevitably be affected,” by export deals like these, Mulumba believes. “Civil society organisations should put pressure on the state to have a deep look into this.”

Brain drain, particularly in the medical field, is a major problem across Africa. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a country have at least one physician for every 1,000 people. According to 2013 figures (pdf) from the ministry of finance, planning, and economic development, Uganda averaged only one doctor for every 24,725 people (0.04 per 1,000) in 2010.

To tackle this issue, Uganda is one of the five countries working with WHO on its “Brain Drain to Brain Gain” project, part of a global effort to balance freedom of movement for medics with the right of patients to receive healthcare at home.

In 2015, the Ugandan health ministry halted a plan to send nearly 300 medics to Trinidad and Tobago, after the government was sued by The Institute of Public Policy and Research (IPPR), a Ugandan think tank, which argued that that the deal violated the constitutional right of Ugandans to have access to basic medical services.

The country’s health worker crisis has not abated since then. According to reports in Uganda’s New Vision newspaper, Kampala alone will need nearly 1,350 specialists such as anesthetists, ear, nose and throat surgeons, consultants, and biomedical engineers for a new referral hospital, while The Association of Surgeons of Uganda has urged the government to hire more specialists.

Uganda’s labor ministry is now distancing itself from the Libya deal. On Aug. 22, its director, Martin Wandera, told Quartz that the foreign affairs ministry will have the final say on the medics’ departure for Libya. Ugandan newspaper The Observer has reported that the labor ministry has refused to clear the company to let recruits get Libya visas.

When asked about the agreement, Uganda’s minister of state for health, Sarah Opendi, told Quartz this week that while Uganda’s universities still attract students for medical training, the department “cannot absorb all of them right now in public service.”

Medics are “out there, they want to work, but because of limited wages we can’t employ them,” Opendi said. That meant the department was reluctant to “interfere…at this point in time” with recruitement efforts like those offered by MEC.

Opendi agreed that medical brain drain was a problem for Uganda, and was something the ministry was trying to address through efforts like making specialist facilities autonomous, so that they could set their own salaries, and not have them pegged to public service rates.

MEC declined further requests for comment, but in early August posted pictures on their Facebook page of their directors inspecting Benghazi operating theaters and announced Ugandans could also expect more jobs from Libya. In an Ugandan tabloid in late August, it called on the labor ministry to “effectively exploit the massive Libyan labor market to the benefit of Ugandans,” and insisted that the country was “safe for Ugandan workers” and “fears concerning (an) unsafe work environment in Libya Benghazi is just a hoax.” The government disagreed.

Patrick was one of an estimated 1,500 people who rushed to the headquarters of MEC in May, forking out 210,000 Ugandan shillings ($60) for the non-refundable registration fee and a mandatory HIV test. But after months of waiting for a visa for Libya, Patrick has now given up, along with others who applied for the much sought-after positions.

“I’m sick of it, more than the word sick,” said one applicant, a pathologist, of working night duty at a hospital for just 1.2 million shillings ($330) a month, a salary he said was often paid weeks late. Still, he had demanded MEC refund the $1,000 he said he paid for flights and a “connection fee” to find him a job in Libya.

But Patrick says that other applicants are still holding out hopes that opportunity waits them in Benghazi.

“They just want one thing: going to Libya. Nothing else,” he said of two friends who applied for nursing positions. “They feel they are safe in Libya, and want to work.”