Yaoundé, Cameroon

The protracted crisis in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions, which has largely grounded schools and courts in the affected areas since November 2016, and threatened tip into full-scale conflict, seems to have no end in sight.

In recent weeks, there have been deadly clashes between government forces and local protesters. Mass arrests in the Anglophone North West and South West regions have also been affected, leaving detention facilities overwhelmed with detainees.

Government and activists have called for dialogue to resolve the crisis. But neither side has taken the required steps to initiate one.

The crisis which erupted last year following industrial strike actions by lawyers and teachers against the imposition of the French language in English courts and schools has its roots in the country’s fragmented colonial history, which started with Germany in the 19th century, and ultimately ended up with Britain and France until independence in the early 1960s.

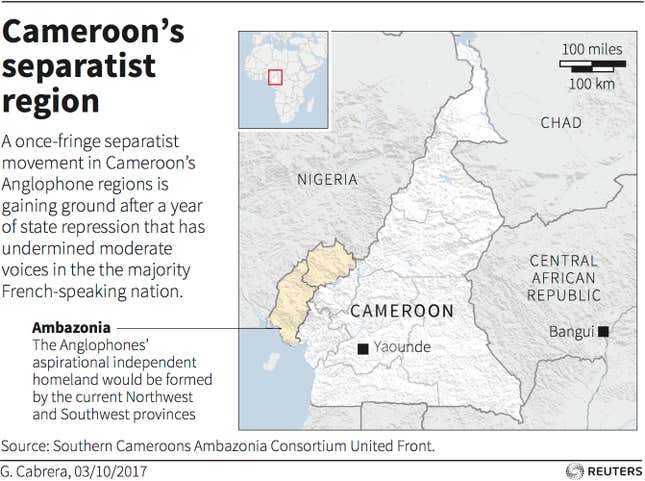

Today’s protesters are now going as far as pushing a separatist agenda, demanding their own breakaway country Amblazonia, made up of the English-speaking regions which border Nigeria’s east.

But in truth, the strike action by activists, which soon turned into a popular uprising, goes far beyond the French/English language divide. For one thing, the division of the colonial languages cuts through ethnic groups. For example the Sawa people speak English in Buea but less than an hour away in Cameroon’s largest city Douala, Sawa people speak French.

Anglophones who make up 20% of Cameroon’s 23 million population have over time felt marginalized by the Francophone-dominated government in the socio-cultural, political and economic spheres. The latest mass protests have merely been a manifestation of frustration arising from long-term deprivation as well as both real and perceived discrimination.

There is significant economic disparity when it comes to allocation of investment projects by the State to the two English-speaking regions, when compared with the other eight French-speaking regions.

In Cameroon’s 2017 public investment budget, home region of president Paul Biya, in the South, was allocated far more resources than the North West and South West regions put together. Going by the country’s government project logbook for the year, the South region was accorded over 570 projects at a total sum of over $ 225 million (FCFA 126 billion).

For its part, the North West region had no more than 500 projects to be executed with over $76 million (FCFA 42 billion), while the South West region had slightly over $77 million (FCFA 43 billion) for over 500 projects.

The projects allocated to the English-speaking regions for 2017 pay little attention to crucial areas like road construction and rehabilitation which is a major concern in this part of the country.

To put this in context of population size, based on the 2008 census the South region had about 761,000 people, while the South West had 1.4 million and North West had 1.7 million.

Politically, few English speakers hold ministerial and other key positions in Biya’s bloated government. The country’s prime minister, head of government, Philemon Yang (an Anglophone) occupies an insignificant fourth position in state protocol, after the head of state, president of the senate and speaker of the national assembly (all Francophones).

More protesters killed

The long-lingering crisis has been threatening to do further damaged to Cameroon’s already battered economy. The government’s heavy-handed approach has only likely exacerbated that impact.

Amnesty International confirmed 17 people were killed during Oct. 1 protests in the Anglophone regions. Though government put the figure at about 10. But some local and regional activist groups have put the number as high as 100 killed.

After the recent mass protests, some residents in the North West and South West regions have been declared missing by family members. A few days after the Oct. 1 clashes, four bodies with bullet wounds were discovered at a local cemetery in the city of Buea. Locals suggested they may have been shot by military helicopters that surveyed the demonstrations.

Many local and international bodies have condemned the killing of unarmed civilians, including the UN High Commission for Human Rights. Washington said the Cameroonian government’s use of force to restrict free expression and peaceful assembly as well as violence by protestors were both “unacceptable”. President Biya, whose whereabouts is officially unknown, is yet to extend condolences to the families of shot victims. But it has been noted that he sent condolences to the victims of the Las Vegas shootings in the United States.

Violence Begets Violence

There are now concerns that the government’s violent response will only serve to radicalize local activists and previously non-activist citizens. “The mass protests are a clear message that people have been touched to the core and it was a show of frustration,” said Dr. Willibroad Dze-Ngwa, a human rights advocate.

Achaleke Christian Leke, a peace activist and Commonwealth Young Person of the Year 2016, posits that the pains orchestrated by the shootings drives people to think more radically. “The government must remember for every one person killed during this civil resistance by the security forces radicalizes at least 500 people.”

An expert in conflict analysis and management, Robert Afuh Tayimlong, said the government’s perceived sluggishness of finding a timely and peaceful resolution of the crisis, may have prompted desperate agitators to resort to unlawful violence.

Human rights watchers fear Cameroon is now likely to have a long-running crisis similar to the one seen in neighboring Nigeria’s Niger-Delta region, just across the border.