James Gubb’s protest art may have cost him dearly, but he says it was all worth it to send the Gupta family a strong, succinct message.

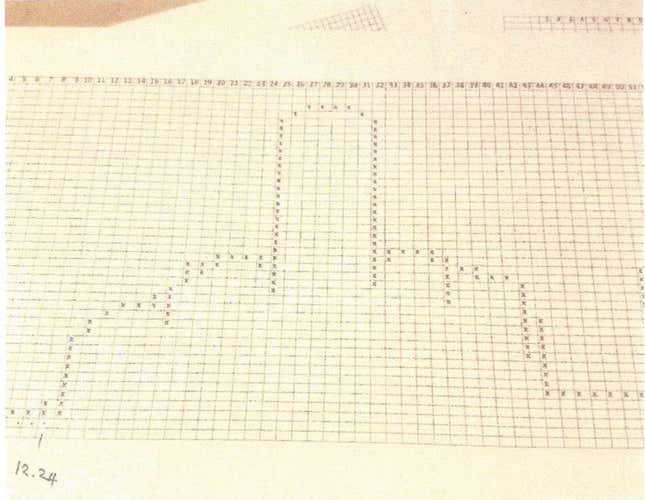

Gubb, a South African trader, bought $28.60 worth of shares in the Gupta family’s Oakbay Investments, a holdings company for businesses that range from mining to media. Using two online accounts, Gubb traded his 22 shares between them to create a share graph pattern in the shape of a clenched-fist and raised middle finger. His stock price protest was made on March 31, in solidarity with thousands of South Africans who marched protest state corruption, he said.

The R400 trade on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange led to a R100,000 (about $7,147) fine from the country’s Financial Services Board for creating an artificial price (pdf) for Oakbay, the board announced on Oct. 31. The fine is 250 times more than what Gubb spent to create his artwork and he admits he is shocked by the penalty but will pay it.

“I literally did exactly what Pravin asked me to do. I connected the dots,” Gubb told a local radio station on Nov. 2. The controversial family with links to president Jacob Zuma has been at the center of a series of corruption scandals that threaten to derail the country’s economy.

South Africa’s former finance minister Pravin Gordhan has been using his public platform to urge citizens to “connect the dots” on corruption and the links between struggling state-owned companies and the wealth so quickly accumulated by the Gupta family, who immigrated from India in the 1990s. Gordhan was fired earlier this year, after much speculation that he was frustrating corruption efforts in state-owned companies.

The Gupta family name has become shorthand for corruption in South Africa. Their businesses have benefitted from various contracts with state-owned enterprises like the national power supplier and the public broadcaster, but a watchdog report revealed the family’s close personal links with president Jacob Zuma. The extent of the Guptas’ influence in government allegedly goes as far as allowing them to handpick cabinet ministers.

Despite the penalty, Gubb feels vindicated that his prank has brought attention to serious questions surrounding Oakbay’s listing in the first place. The holdings company was forced to delist from the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in July after no firm would act as its sponsor or secretary in the wake of a string of corruption allegations.

Just this week, an investigative report detailed how Oakbay allegedly inflated their share price by lending money to a Singapore firm so they could in turn buy shares on the South African stock exchange. South Africa’s Industrial Development Corporation, a state agency aimed at supporting industrialization of the economy, stands to lose millions after buying an inflated 3% stake in the company—just the kind of trade Gubb says he wishes authorities were more vigilant about.