African countries have worked hard to improve children’s access to basic education, but there’s still significant work to be done. Today, 32.6 million children of primary-school age and 25.7 million adolescents are not going to school in sub-Saharan Africa.

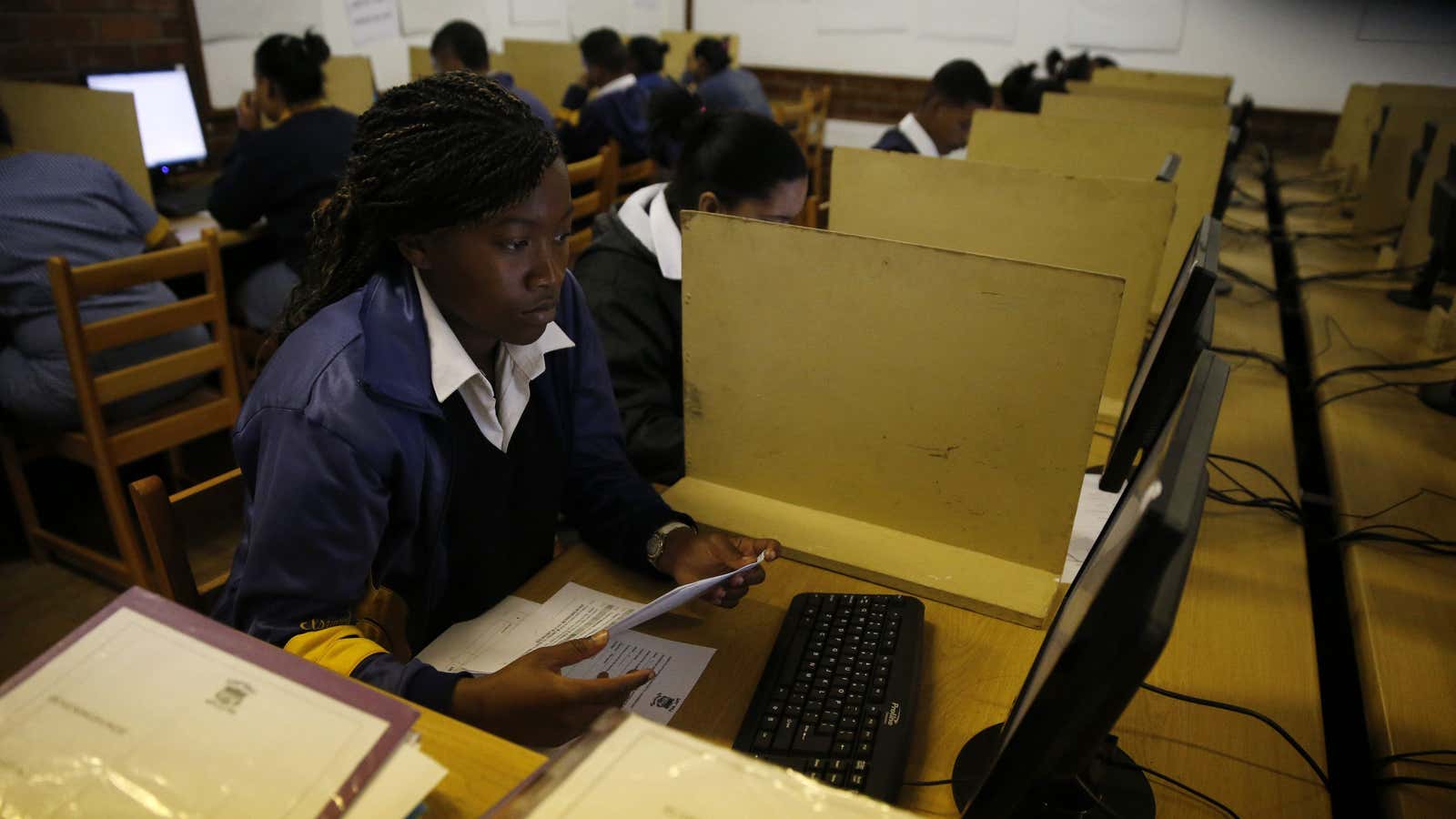

The quality of education also remains a significant issue, but there’s a possibility the technology could be part of the solution. The digital revolution currently under way in the region has led to a boom in trials using information and communication technology (ICT) in education – both in and out of the classroom.

A study carried out by the French Development Agency (AFD), the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie (AUF), Orange and Unesco shows that ICT in education in general, and mobile learning in particular, offers a number of possible benefits. These include access to low-cost teaching resources, added value compared to traditional teaching and a complementary solution for teacher training.

This means that there’s a huge potential to reach those excluded from education systems. The quality of knowledge and skills that are taught can also be improved.

The irresistible digital revolution

Access to means of communication is now a key part of daily life for the vast majority of people living in Africa. Mobile telephone prices and the cost of communication have dropped. Mobile telephone use has increased from 5% in 2003 to 73% in 2014. There are 650 million mobile phone owners on the continent (more than the US and Europe combined) and 3G mobile networks are growing rapidly.

Costs are falling and rural areas will soon be reachable thanks to a number of developments. These include undersea cables connecting Africa to other continents, fibre-optic cables that provide connectivity within the continent and recent satellite connection plans. Access to wired Internet remains low with 11% of households connected. But access to mobile Internet is already helping the region catch up. Smartphone penetration levels should reach 20% in 2017.

This rapid expansion of mobile Internet services is already contributing to the region’s economic and social development. This is particularly the case in areas such as financial inclusion (mobile banking), health (mobile health) and farmers’ productivity.

Given the features of mobile telephones (voice calling, text messaging) and smartphones (reading texts and documents, MP3, images and video) and their wide availability, their potential for improving access and quality of educational services is also boundless.

M-learning (or m-education) – educational services via a connected mobile device – is the main lever for growth in educational information and communication technology and for making content available. This could be for learning (teacher training, learner-centred teaching, tests) or making up for the lack of data for education system management.

New technologies for learning

Mass communication technology has been used as a principal driver of education in Africa since the 1960s. Countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Niger and Senegal developed major programmes using radio and then television to promote basic education, improve teacher training and even teaching pupils directly. These programmes reached a high number of pupils at a relatively low cost. But results in terms of academic performance remain difficult to evaluate.

The mass distribution of computer hardware then took over in the 1990s. Many national and international programmes started to concentrate on equipping schools with computers to facilitate digital education and offer new educational media in the form of educational software and CD-ROMs. Use was mainly centred on schools. But trials were often launched without clear pedagogical objectives and state-defined policy frameworks.

The arrival of personal computers in the 2000s facilitated the individualisation of school ICT. The US One Laptop per Child project, launched in several African countries in 2005, aimed to equip schools with laptops at low cost.

Nearly 2 million teachers and pupils are involved in this programme across the world. More than 2.4 million computers (at a cost of around $200 including an open teaching platform) have been delivered. Evaluations show that the use of portable or fixed computers in the classroom has only a limited effect on pupils’ academic performance. But it may have a positive impact on certain cognitive abilities if pupils can use their computers at home in the evening.

Contents and uses

Since 2010 the large-scale diffusion of mobile communications technology has transformed practices with easier access to educational resources in and outside school. The arrival of low-cost, low-consumption smartphones and tablets allows ICT in education to gradually move out of the school environment.

There has been a shift from a tool-based approach to one that’s centred on content and use. These mobile tools, particularly tablets, offer important opportunities to tackle the lack of books and textbooks. The distribution of Kindle-style readers to 600,000 children in nine African countries has seen a considerable impact on reading and on pupils’ results in educational tests.

The sending of text messaging containing short lessons, multiple choice tests or audio recordings have also been shown to have an important effect on teachers. This is also true of MOOCs (massive open online courses) adapted to African countries’ needs and capacities.

The cross-fertilisation of teaching models and tools has broadened the potential of information and communication technology in education. Some technologies, perceived as outdated, are undergoing a partial revival thanks to the combination of media that can be used in any single project. For example radio and television programmes are inexpensive and attract a considerable audience. Combined with Internet and mobile phones they provide promising educational results.

The BBC’s Janala English-instruction programme for the people of Bangladesh is a good example of cooperation between very diverse actors.

What are the conditions for success?

Most African countries are showing an interest in technology in education. But a range of conditions must be satisfied to ensure that they are deployed efficiently within the educational landscape. This includes:

- Responding to technical and economic constraints

- Responding to users’ needs and strengthening their capacities

- Finding sustainable funding models

- Facilitating effective multi-stakeholder collaboration.

Although the time for innovation and experiment will never end, now is the moment to put systems and strategies in place for moving to the next level, particularly by setting up stakeholder coalitions. ICT will not resolve all of Africa’s education problems. But it can help to fundamentally change the current paradigm of skills development systems.

This article was co-authored with Erwan Lequentrec (Orange Labs) and Francesc Pedró (Unesco). The text is based on “Digital Services for Education in Africa”, written by David Ménascé and Flore Clément.

Rohen d’Aiglepierre, PhD, chargé de recherche « Capital humain » / “Human Capital” reseacher, AFD (Agence française de développement); Amélie Aubert, Chef de projet « Éducation, formation, emploi », AFD (Agence française de développement), and Pierre-Jean Loiret, Responsable du numérique éducatif, Agence universitaire de la francophonie (AUF)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.