At first glance, Black Friday in South Africa looks a lot like it does in the US. Sales, soft news pieces on how to get the best deals, and solemn complaints about consumer culture.

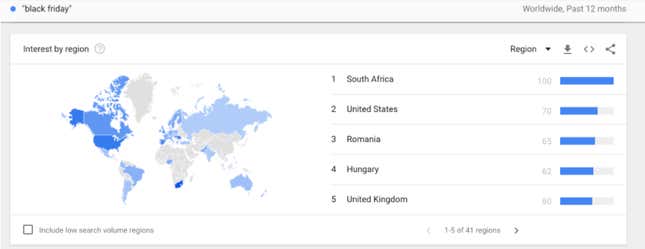

A local website even reported earlier this week (Nov. 20) that South African interest in the holiday on Google Trends rivals that of the US, with “Black Friday” ranking higher in searches from South Africa over a 12 month period, when adjusted for population and total searches.

But first glances don’t tell the whole story.

Despite not celebrating Thanksgiving, South African retailers began advertising Black Friday deals in South Africa a few years ago. The holiday found fertile ground in a country that celebrates Christmas, has a well-established mall culture, and loves holiday shopping. But even with recent growth, South Africa’s online retailing sector is relatively small compared to the US. As an American who lived in South Africa for more than 10 years, I wondered: Why would “Black Friday” be such a popular Google search term in South Africa?

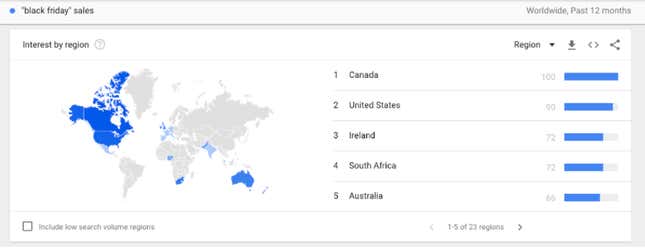

When you search Google Trends for “Black Friday,” it’s true that South Africa tops the list. However, if you change the search terms to “Black Friday” and “sales,” South Africa drops to fourth for Black Friday interest, behind the US and Canada.

What accounts for the country’s outsized interest in a holiday beyond the sales? One possibility has to do with a meme that regularly makes the rounds of the nation’s social media, particularly on the accounts of the country’s black and digitally-connected youth. It claims “Black Friday” has origins in the sale of black slaves in the antebellum American South after Thanksgiving.

“It was the day after Thanksgiving when slave traders would sell slaves for a discount to assist plantation owners with more helpers for the upcoming winter,” reads one of the pictures frequently circulated as part of the meme. South Africans aren’t the only ones who have fallen for the claim—New York Knicks guard J.R. Smith and singer Toni Braxton fell for it in 2014.

The meme isn’t true. While the origins of the term “Black Friday” are hard to pin down, fact-checking site Snopes writes that it made its first appearance in newsprint in reference to workers who called in sick the day after Thanksgiving. Another urban legend claiming that Black Friday has to do with the day in the calendar when retailers started turning a profit is also probably not true.

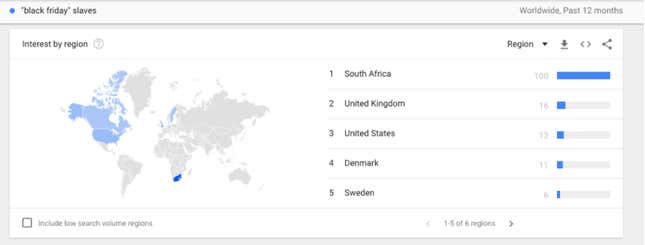

Indeed, if you search “Black Friday” and “slaves” or “slavery” on Google Trends, South Africa jumps back to first position in interest, far ahead of the US.

Social media has given young black South Africans a wider avenue to voice their opinion and share information outside of the country’s mainstream media, which, though more diverse now, has been historically white and has marginalized black viewpoints. It’s not a surprise that a meme like this would provoke interest.

Still, you couldn’t have a Black Friday meme in South Africa without interest in the event itself. That interest has been rapidly growing in Africa, but particularly in South Africa, as consumers respond to a faltering economy by searching for deals. “The current tough economic environment and poor consumer confidence has led to consumer demands shifting towards products or retailers offering good value for money,” says Euromonitor senior research analyst Christy Tawaii.

South Africa’s Black Friday deals include the usual flat-screen TVs and PlayStations. There are also a lot of liquor sales, fairly traditional for the South African Christmas season, which falls during the summer and often combines the best parts of an extended family holiday with outdoor barbecuing.

You’ll also find regular household items like groceries and diapers. The Christmas season is a time for many of South Africa’s migrant workers to return home from the cities where they work, laden not just with gifts but also basic items like dry goods. In that context, taking advantage of a 50%-off Black Friday sale for items like laundry detergent makes a lot more sense.

That said, while South Africans are adopting Black Friday, it’s arguably not changing what they buy so much as when they buy it, Tawaii says. “As a result of Black Friday, South African consumers are changing their purchasing patterns, with many shifting their Christmas shopping to November due to the heaving discounting offered. In 2016, retailers reported slowdown in retail sales growth in December, following the sharp increase in November due to Black Friday sales.”

Black Friday is far from the only aspect of American culture that South Africans have an affinity for. Many, especially the relatively affluent, have developed a taste for American food and beverage brands, particularly in recent years. Starbucks and Krispy Kreme’s arrival in the country were met with national news coverage and long lines in a country with no shortage of coffee and pastries. When Burger King opened in Sandton, South Africa’s corporate hub, in 2014, the line stretched out the door for months.

But as Google Trends show, it’s not just good deals, holiday shopping, and enthusiasm for American commercial habits and goods that account for interest in Black Friday. It’s also critiques given voice on social media by young, digitally-conscious black people—even if it’s over a false meme.