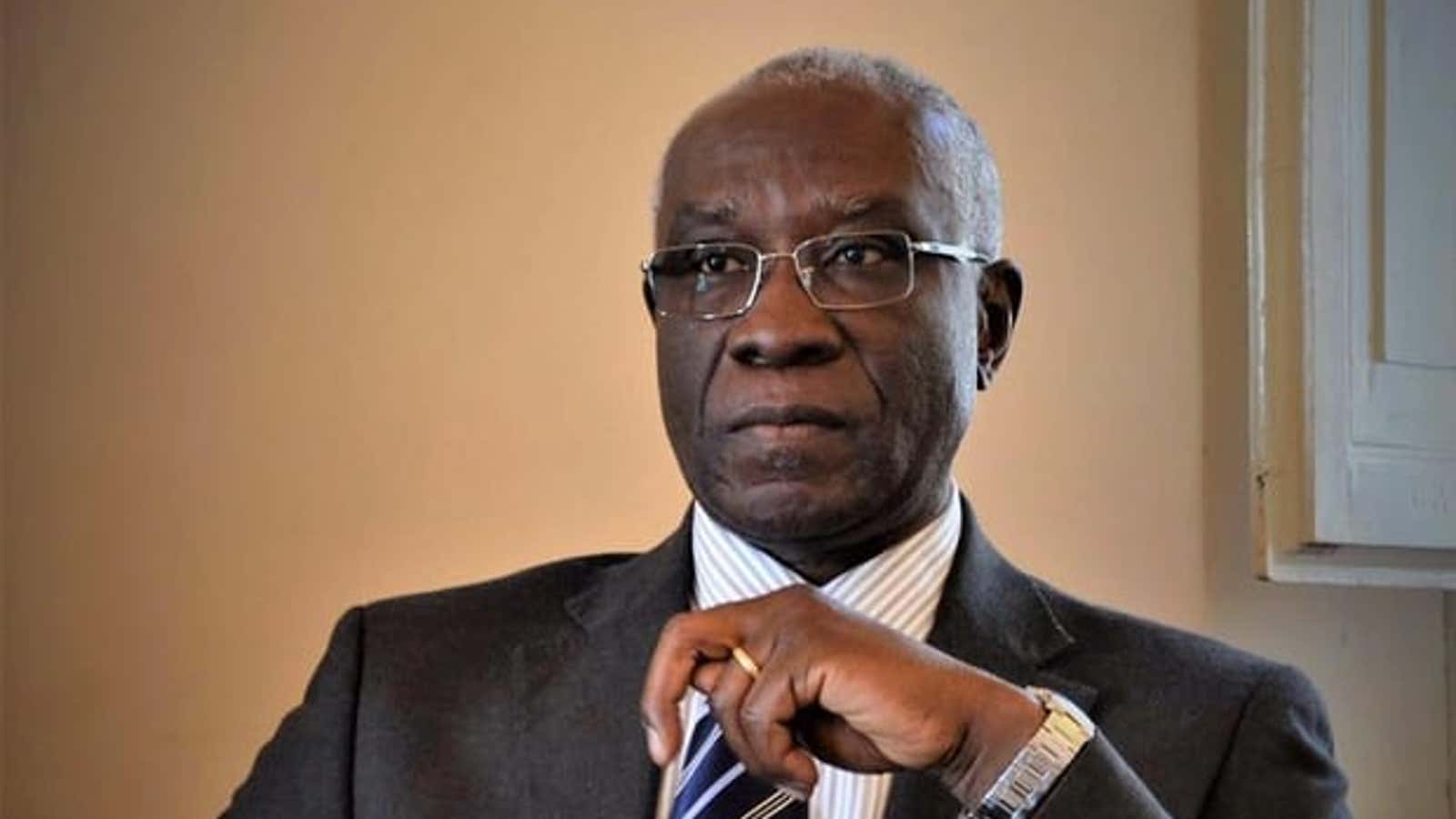

The recent election of Nigerian-born Mr Anthony (Toni) Chike Iwobi as a Senator at the Italian Parliament of the far-right, Populist Party of the Ligue (La Lega), has brought into sharp relief the question of racism and xenophobia in the country.

Iwobi is not only the first Senator of African origin to have been elected in Italy. He’s also the first person from sub-Saharan Africa to have been elected to represent a far-right party, la Lega (The League) led by Matteo Salvini.

But his election is unlikely to lead to less racism and xenophobia in the country nor will it bring any respite for migrants in the country. This is for two reasons: racism and xenophobia have become more entrenched in Italy, and neither Iwobi’s party, nor the senator himself, are sympathetic towards migrants.

In recent years both Italians and outside observers have become increasingly concerned about the rise of xenophobia in the country. Italian anti-racism groups and international human rights institutions have greater and greater intolerance.

The momentum picked up over the past year. Xenophobia spread, fuelled by fake news which targeted Italian political personalities seen to hold more liberal views.

In February 2018, just weeks before the election of Iwobi, Amnesty International declared that Italy was, “steeped in hatred, racism and xenophobia, and unjustified fear of the other.”

It added that 50% of discriminatory, racist, and hate speech came from the League leader Salvini himself.

Migrants in Italy are increasingly seen as a threat to society. The centre-right coalition, which attracted the highest percentage of votes in the recent elections, focused its campaign on the slogan “Italians first”. The leader of the coalition Silvio Berlusconi even declared that “migrants are a social bomb.”

Iwobi is likely to be part of the problem, rather than part of campaign to end racism and xenophobia in the country. This is because his views towards migrants aren’t very sympathetic. As he put it:

There are two types of immigration: regular immigration, which is welcome, and illegal immigration, which is a crime everywhere except in Italy. Why import new poor people without being able to guarantee them a future?

And at a conference in Abuja in 2015, he said he would not want to discourage his people from travelling but “he would rather advise them to stay at home where it is more secure.”

This is a peculiar assertion given that in 2017 the World Economic Forum ranked Nigeria the fifth most dangerous country in the world.

Rise of xenophobia

In 1985, the number of foreign-born people in Italy holding a residence permit was estimated at about 423,000. Between 2016-2017 the total number of non EU-citizens had risen to 3,714,137. Most were from Morocco (454,817).

The new flows of migrants have created tensions. But racism and xenophobia have been on the rise for over a decade.

In 2008, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern about hate speech in the country. This included comments by politicians, negative attitudes and stereotypes directed at foreigners and the minority Roma people as well as their ill-treatment by law enforcement officers during camp raids. The committee urged Italy to:

take resolute action to counter any tendency, especially from politicians, to target, stigmatize, stereotype or profile people on the basis of race, colour, descent and national or ethnic origin or to use racist propaganda for political purposes.

Two years later Navi Pillay, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, expressed her “considerable concern at the authorities’ policy of treating migrants and the Roma as, above all, a security problem rather than one of social inclusion.” She expressed

alarm at the often extraordinarily negative portrayal of both migrants and Roma in some parts of the media, and by some politicians and other authorities.

In March 2011, Human Rights Watch published a report entitled “Everyday Intolerance: Racist and Xenophobic Violence in Italy”. The report pointed to “worrying signs exist that increasing diversity has led to increasing intolerance, with some resorting to or choosing violence to express racist or xenophobic sentiments.”

The current reality for African immigrants is that it’s become increasingly difficult to become a legal migrant. Forced returns have been accelerated. This is true even to countries with dictatorships such as Sudan, or where there are systematic violations of human rights such as Libya.

And migrants have been made more vulnerable. There’s been a reduction in the jurisdictional guarantees for asylum-seekers and appeals for rejected claims are increasingly being denied.

False stereotypes

One of the false stereotypes about migrants in Italy is that they want to remain in the country. In fact, a study done by the International Migration Organisation, in 2016 found that migrants arriving in Italy didn’t have any destination in mind.

In addition, according to a recent report of Medecins sand Frontieres, Italy doesn’t have adequate reception policies for migrants. About 10,000 are living in inhumane conditions in informal settlements with limited access to basic services.

Yet in September 2017 the previous government presented its first official plan for the integration of migrants. This included objectives such as teaching new arrivals Italian. In addition, the government committed to promoting training and apprenticeship schemes for migrants.

But, in this climate, the situation for migrants in Italy doesn’t seem rosy – at least for now and the imminent future.

Italy still doesn’t have a government given the fractured outcome of the elections. But, giving that the centre-right, anti-immigrant coalition (including the Ligue) got the highest number of votes, it’s likely that the new government will be headed by a centre-right leader whose ideas will not favour integrating African migrants.

A recent banner, portrayed at a school, where a debate on the integration of migrants was to be held in 2017 portrayed the climate surrounding African migrants in Italy:

Non ci sono negri italiani (There are no black Italians).

Cristiano D’Orsi, Research Fellow and Lecturer at the South African Research Chair in International Law (SARCIL), University of Johannesburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.