Dr. Abiy Ahmed Ali was sworn-in as the new Prime Minister of Ethiopia on April 2, 2018. He will succeed Hailemariam Desalegn who resigned in the midst of a heightened political crisis in Feb. 2018 after five and a half years at the helm.

The seemingly peaceful power transfer in Addis Ababa is a welcome gesture, but it betrays the ongoing struggle the country has had to endure for the last three years, including the current six-month state of emergency. A highly coordinated media censorship has ensured that only a fraction of what is happening in Africa’s second most populous country is visible. As Abiy Ahmed takes over Ethiopia’s most powerful constitutional office, he has the responsibility of lifting the lid on media censorship, if the opportunity for reforms is to take root outside Addis Ababa.

To be sure, the new prime minister has an overflowing to-do list. Lifting the state of emergency is widely seen by a broad range of Ethiopians and human rights groups as a top priority and signal of progress. However, recent trends by the Command Post, the bureau responsible for managing the state of emergency, may be eroding the high hopes the population has in this rare political opportunity. After the much-publicized release of political prisoners in mid-February, the Command Post re-arrested 29 journalists and lecturers, among them Eskinder Nega, the celebrated winner of 2012 PEN award.

In the Southern Oromia region, thousands of Ethiopians have been displaced, with some crossing over to Kenya’s northern region, to escape the military violence unleashed by the Command Post. The economy, the one sector the government has harped on to cover up for closed political space, has suffered heavy losses, thanks in large part to an unpredictable business environment and cost of doing business. The political questions of uniting the country, jump-starting the economy, and responding to the humanitarian situation in Ethiopia are all competing priorities deserving immediate attention.

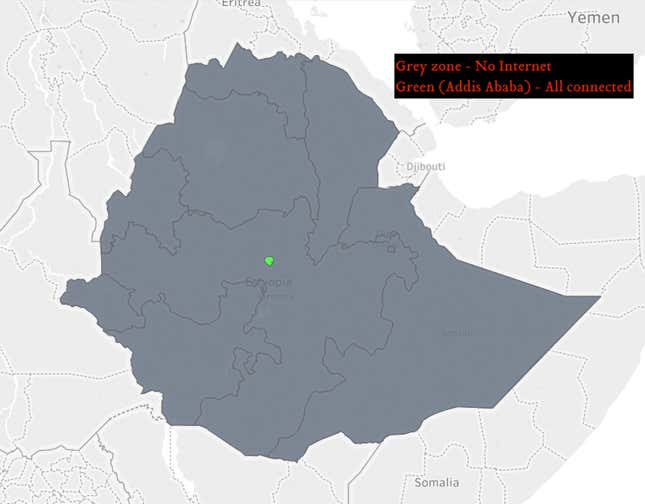

However, a yarn connecting all the above is the media blockage. Only the capital city has had access to the Internet since mid-December after the government imposed a blanket shutdown for regional states. Independent media is almost non-existent after the Meles Zenawi-led government closed them down during and after the controversial 2005 election. The subsequent arrest of journalists and opposition leaders saw a mass exodus of public intellectuals to safer grounds. There is currently no independent newspaper compared to more than ten in 2005, less than ten radio stations and only one internet service provider fully owned by the government. The media vacuum created by the events of 2005 onwards limited civil and political space considerably.

The diaspora community attempted to fill the media vacuum in Ethiopia using satellite radio, television and internet platforms. Successful examples include Ethiopia Satellite TV and Oromia Media Network, which attract millions of followers. No keen observer of Ethiopian politics can doubt the central role Oromia Media played in broadcasting the popular protests and civil disobedience happening in isolated towns, effectively shaping the political narrative both inside Ethiopia and in the diaspora.

As Internet penetration grew, so did the salience of these platforms, a reality never lost on the government. Internet shutdowns, website censorship, and targeted surveillance were meant to limit their audience. For example, OMN and ESAT websites are permanently blocked in Ethiopia, and accessing them is prohibited by law while their satellite TV signals are occasionally jammed.

The trend above illustrates the turbulent state of internet connectivity in Ethiopia. Point (a) shows two short-lived deeps which were the shutdowns during 2016 national exams, (b) is a longer and wider deep which starts off during the state of emergency in Oct. 2016, (c) is the 2017 national exams when the government ordered a total national blackout, (d) illustrates a return to active protests and online activity after the state of emergency was lifted, and (e) points to the shutdown that started mid-Dec. 2017 targeting all regions in the country except the capital, Addis Ababa. A second state of emergency was declared in Feb. 2018, and as the chart illustrates, the country is still under an internet shutdown. In summary, Ethiopia’s internet connectivity has never recovered since Nov. 2015 when the protests started in earnest.

Yet, it is because of the relentless efforts by Ethiopians to innovate and adapt the internet to local offline resistance networks that political power is shifting from the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front to Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization.

Three things, I propose, make the opening, not closing, of the internet across the country central to Abiy’s political success. One, it will act as a litmus test on where he is located principally as a political reformer. Any indecision on an issue as unjustifiable as a blanket internet shut down for 90% of the country will portray him as an opportunist who rode to the high office on the blood, jail terms, and ingenuity of internet warriors only to lock them out while in power. Addis Ababa alone cannot sustain the popular narrative of change.

Two, the economic costs of media censorship have been demonstrated to cripple economies, especially when this happens for an extended period of time. An internet blackout costs an economy like Ethiopia’s an estimated $1 million a day. An open internet is a necessity to jump-start the limping economy after three years of uncertainty.

Three, an open independent media allows for fair coverage of the country, setting realistic expectations, as opposed to the ‘development’ rhetoric churned out as propaganda and regurgitated by uncritical international media. This ‘public relations’ type of media coverage sets impossible standards that sees the government harshly covering up the human rights costs of the ‘fastest growing economy’ narrative, only for the suppression to boil over, as happened with the protests. It makes governance easier when attention is on fixing what is broken rather than maintaining expensive PR firms in global metropolises for the myopic focus on ‘foreign’ investors.

Prime minister Abiy Ahmed, himself a computer engineer, knows that switching the internet back on in the country is not only expected of any modern nation but is a direct boost to his economic plans. Abiy is a benefactor of the human rights space created by the internet, ironically having set up and directed the Information Network Security Agency (INSA), an agency notorious for cyber surveillance and website censorship.

Any delay may be interpreted as a continuation of the old ways and may foment the next wave of resistance. Should this opportunity be squandered, the benefit of the doubt the protestors gave to the political class in 2018 may no longer be an option.

This article was originally published on Moses Karanja’s Technology & Public Policy blog.