One of the Netherlands’ most prestigious universities is offering a twist to its African studies curriculum. With a blog post titled, “African Studies ‘goes animal'” Leiden University announced a new research project to include “animal perspectives” in the programs of its African Studies Centre. While well intentioned, the project raises uncomfortable questions about the representation of Africans.

Led by organizational anthropologist Harry Wels, the research project aims to include the perspective of animals in a social science traditionally focused on humans. In the face of increasing scientific evidence that animal behavior is more complex than previously thought, Wels wants the discipline of African Studies to participate in this growing understanding of animals and their interactions with humans and each other.

“So far, non-human animals did not feature much in African Studies; African Studies’ genealogy is rather focused on humans: African Studies is anthropocentric in its approach to Africa,” Wels wrote in the blog post.

The project includes one of the most popular trends in social science right now, “intersectionality.” While intersectionality is usually used to explain how political, cultural, gender, and other identities intersect to offer diverse perspectives, Wels’ team wants to add species to the framework. He specifically uses the examples of the colonial plundering of Africa’s environment and the global outcry surrounding the hunting of Cecil the Lion.

The so-called ‘animal turn’ in the social sciences is a valid area of research, but positioning it in African Studies in this way is a “poor choice” because it could create a “false equivalence between human experiences and animal experiences,” says Nicole Beardsworth, a doctoral candidate at the University of Warwick.

“This is especially the case in Africa where animal’s experiences are often treated with more care than people’s,” said Beardworth. “Cecil the Lion is a case in point.”

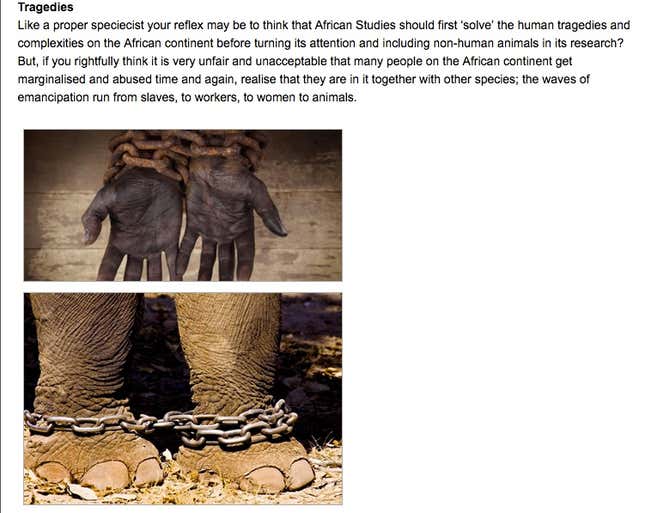

The project’s announcement inadvertently plays into a derogatory representation of Africans that has been used for centuries, most recently in a photographic exhibition in China that used side-by-side images to compare Africans to apes and monkeys. While Wels isn’t deliberately trying to compare Africans to animals, he nonetheless plays into a narrative that has been used to oppress and subjugate Africans by painting them as inferior. There is an image Wels uses in the blog post that is particularly perplexing, and reminds us of this narrative: The image of a shackled African juxtaposed with a chained animal.

In an email to Quartz, Wels said he does “not equate human and animal suffering!”

“I am VERY much aware of the offensive history of side-by-side comparisons of animals and Africans,” Wels said. “I am also very much aware of my own positionality as a white European male (of a certain age ;-)) in academia in general and in African Studies and this debate in particular.”

Wels’ project is part of the growing challenge to anthropocentrism, a human-centered approach to theory. It’s a view rooted in European traditions of continental and analytic philosophy, western traditions of religious thought, and Darwinism.

This also happens to be a position that has not only excluded African perspectives, anthropocentrism has also been used as the theoretic underpinning for harsh policies. As Immanuel Kant’s thinking contributed to the enlightenment that gave the world its concept of human rights, he also held deeply disturbing views on race. Similarly, Charles Darwin, who helped the world understand evolution, was held offensive beliefs regarding Australia’s native people.

Wels’ approach to animal perspectives has value in raising awareness and empathy about poaching and other forms of environmental degradation. Yet, its positioning in African Studies is problematic. A look at Leiden’s North American, Latin American and Asian Studies, give no indication of similar attempts to include animal perspectives. It could be argued European, American, and Asian industrialization has come at the expense of the natural environment.

African academic disciplines, like political theory and science, philosophy and design, are already burdened with proving their worth to their international peers in the first place. On a continent still fighting for its place at the academic table, this will not amplify the ignored voices of Africans.